1. Introduction

Nursing is a demanding field with constant challenges. Reeves [1] described the field as complex and requiring constant interaction with various individuals from patients to coworkers, to physicians. In order to become licensed as a nurse, students must complete rigorous educational requirements and then pass a national licensing exam. Stress can begin early in the educational process [2-5]. Many students may feel overwhelmed with academic rigor, content, and unprepared for practice in the real world [3,6], which may affect their health [7,8,9].

Perfectionism has been shown to be a mediator of stress [7,11,12]. Although there have been comparisons among college students and perfectionism [7,11-13], a comparison of perfectionism among nursing students is lacking in the literature. Perfectionism can cause maladaptive behaviors that may interfere with a student’s education and well-being [7]. The subsequent maladaptive traits that follow negative perfectionism in college students should be recognized in order for interventions to be developed, and help students cope in a more effective manner [7,10,11,13,17].

2. Literature Review

2.1 Perfectionism as mediator of stress

The perception of stress is caused by many different contributions and perfectionism has been identified as one negative contributor [7,10,11]. College students need motivation in order to succeed, which can result in feelings of accomplishment, but excessively high standards can lead to a vicious cycle of low self-esteem. Perfectionismdiffers from normal motivations to achieve and can be maladaptive. Perfectionism can be a motivator for success, but has been referred to as high, impractical values entangled with significant self-criticism [7,18]. Perfectionists participate in self-ruminating as well as constant playback of mistakes [17,19]. Perfectionism can affect students on varying levels from severe maladjustment to more moderate effects. Some studies have shown perfectionism can play a role in self-injury in college students [8,14]. Self-critical perfectionism has been shown as correlation with self-critical depression and anxiety in undergraduate psychology students [7].

Hibbard and Davies [13] looked at perfectionism in undergraduate students at two distinctly different learning environments consisting of both private and public universities. The authors concluded that private university students exhibited more perfectionism than public university students. Private university students were more concerned about mistakes, possessed higher standards, and had more worries about their capabilities than public university students.

Studies are lacking comparing health profession students and their stress perceptions, and also limited research on perfectionism as a cause of stress within this population. Dutta, et al.[20] reported in a literature review on identified stressors that may cause psychiatric symptoms as a negative side effect from stress among dental, medical, nursing, and pharmacy students. The authors listed the highest incidence of stress found in medical students, then dental students,followed by nursing students. A heavy emphasis was noted on the strenuous education rigor that health profession students undergo.

Many medical students are exposed to perceived harassment by clinical staff, other students, and instructors.

Perfectionism is a driving force of negative stress in some nurses. Hajloo, et al. [21] indicated that perfectionism contributed to job burnout. Furthermore, younger nurses exhibited more perfectionism than older nurses resulting in decreased job satisfaction. Henning et al. [12] showed higher than expected (27.5%) of students surveyed (medical, nursing, and pharmacy students) exhibited psychiatric levels of distress that correlated perfectionism with this distress.

2.2 Nursing student stress

Nursing school is very demanding for students due to the academic rigor. Students are required to complete academic classroom work and clinical experiences. Students have collectively complained that there is a chief stressor occurring between clinical practice and academic theory [2-4,22-24]. Students are taught theory in the classroom and practice in labs that is not sufficient with what is needed to prepare them for the clinical arena. This practical gap causes stress in the clinical area forming important relationships with assigned staff nurses [2,25]. There are other identified stressors by nursing students that include the fear of making mistakes, questioning one’s ability to perform or lacking confidence in performance, and instructor feedback [1,4,5,24,25]. The effect of negative stress on learning is also a contributing factor for nursing students. Skills are very important in clinical performance by students. It has been shown that nursing students facing negative stress perform significantly lower and make more mistakes [2,3,22]. The low performance by students has a negative cycle and creates frustration for them, andmay produce additional perceived stress. Students have also identified academic load as a significant stressor, which can contribute to inadequate preparation in the didactic and clinical courses [1,2,6,26]. Nursing students, like other college students, report difficulty finding balance of schooling, work, and life [7,24,26].

2.3 Hypothesis

The following hypothesis was addressed within this quantitative study:

Hypothesis 1: Nursing students will show a higher rate of perfectionism than the general population.

2.4 Purpose

The purpose of this research project was to measure negative perfectionism among nursing students. . Although many studies have investigated the relationship between perfectionism among college students, little is known about the manifestations of perfectionism among nursing students. This study has investigated this relationship among nursing students. Negative perfectionism can affect individuals in many maladaptive behaviors [7,8,16]. These behaviors may include anxiety, guilt, hostility, depression, procrastination, and suicidal ideation in elevated cases [7,16]. Understanding, identifying, and recognizing perfectionism among nursing students can possibly lead to healthy interventions that help students in the long term [17].

3. Methodology

3.1 Introduction

In order to understand the relationship of perfectionism among nursing students a quantitative research approach was employed. The subjects of this study consisted of a non-probability convenience sample of 247 nursing students at a large United States western university. The surveys were administered to nursing students in the associate degree and bachelor degrees respectively. Internal Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the university.

3.2 Instrument

The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale [16] was utilized to evaluate perfectionism among nursing students in this study. This tool utilizes a 45 question survey to assess negative perfectionism. Three specific areas are measured, instead of one universal overview of perfectionism, which includes self-oriented perfectionism, otheroriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Selforiented perfectionism may demonstrate impractical pressure to always perform at the top. These individuals set very high goals, but upon achieving them they do not feel satisfied. These individuals may experience a high degree of self-imposed stress and suffer low self-esteem. Other oriented perfectionists have unrealistic expectations of others surrounding them. They may expect others to achieve unrealistic high standards, but also similar to self-oriented perfectionist do not feel gratitude if the goals are achieved. They have a low tolerance for others who do not succeed. Socially prescribed perfectionists are driven by perceived unrealistic expectations of others such as friends, coworkers, or family. These individuals also do not feel satisfied if they succeed, but rather may suffer from low selfesteem. These individuals may also procrastinate. The MPS consists of 45 questions that utilize a Likert scale. The items measured in the MPS have a good internal consistency (Chronbach’s α = 0.86). The MPS has also been shown to have favorable reliability over time (0.88). The MPS has a large normative sample (N=3640). The scores are also gender and age normed [27].

Hewitt and Flett [27] have also identified many negative correlates of elevated perfectionism in each category of self-oriented, otheroriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Some maladjustment correlates of elevated self-oriented perfectionism include “depression, suicidal thoughts, hostility, anxiety, anger, guilt, irrationality, hopelessness, self-blame, and low self-esteem” (p. 23). Some important interpersonal negative correlates include “demand for approval, emotional sensitivity, professional distress, interpersonal hassles, and no admission of need for help” (p. 24). Personality correlates of high self-oriented perfectionism may include narcissism, frustration reactivity, neuroticism, and desire for control” (p. 25).

Hewitt and Flett [28] found maladjustment correlates among individuals with elevated other-oriented perfectionist may include “phobias, irrational self-worth, less positive emotional coping, low frustration tolerance, irrational beliefs, and hypomania” (p. 23). Interpersonal correlates showed “authoritarianism, dominance, negative social interactions, emotional expressiveness, and emotional sensitivity” (p. 24). Personality correlates indicated “histrionic tendencies, antisocial, angry, compulsive behavior, less flexibility, passive aggressive behaviors, and dominance” (p. 25).

Hewitt and Flett [28] also discussed maladjustment correlates in individuals with elevated socially prescribed perfectionism who may demonstrate suicidal thoughts, self-criticism, depression, hostility, shaming, fears of making mistakes, fears of looking foolish, fears of failure, loneliness, and emotional exhaustion” (p. 23). Interpersonal correlates show “blaming, demand for approval, negative social interactions, shyness, shaming, less openness, and submissive behaviors” (p. 24). Personality correlates included “avoidance, Type A cognitions, cynicism, less social efficacy, and less attitude flexibility” (p. 25).

Scoring high in all three categories of perfectionism was also a concern. Hewitt and Flett [28] report that these individuals may exhibit profound depression, anxiety, anger, suicidal tendencies, intimate and work-related interpersonal problems” (p. 25). These individuals may suffer detrimental interpersonal relationships that are tenuous, and they may constantly question their individual identity.

3.3 Analysis of data

A quantitative approach to this project was chosen due to the intent of measurement of the data. The measurement of high MPS scores and associated maladaptive behavior has been established through many other studies [7,8,11,13,16,27,28].

The data was analyzed by converting MPS survey scores to simple T-scores. T-scores are calculated from raw data that balances the data by having the same mean and standard deviation. The T-score helps normalize the data so it can statistically compare to other populations and groups who have previously completed the MPS survey. The mean scores are set at 50 and the standard deviation is set at 10. Age and gender are accounted for in T score analysis. All completed MPS surveys can be compared to these set levels. Those scoring above 50 have scored above the mean and those scoring below 50 have scored below the mean. Higher T-scores are reported with greater number and frequency of problems. Individuals scoring between one-half and one standard deviation (55 and 59) above the mean can be interpreted to demonstrate moderate perfectionism. T-scores of 60 represent one standard deviation away from the mean and associated with clinically significant pathological problems [28].

4. Results

The authors surveyed a total of 247 students. Two students did not complete the survey and were excluded. There were a 213 females and 32 males who completed the surveys (n=245). The ages were categorized according to T score analysis and ranged from 18 to 45 years of age. There were 100 students ranging from 18-24 years of age, 92 students ranging from 25-34, 45 students ranging from 35-44, and 8 students greater than 44 years of age (Figure 1).

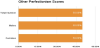

The study results revealed 160 students (65%) scored moderate to elevated levels of perfectionism in the self-oriented perfectionism category. Females students (66%) scored higher than males students (63%) (Figure 2). The study indicated 118 students (48%) demonstrated elevated levels of perfectionism in the self-perfectionism (Figure 6). Females students (49 %) scored higher than male students (41%).

In the other-oriented perfectionism category, 123 students (50%) presented with moderate to elevated levels of perfectionism. Males (50%) were equal to females (50%) (Figure 3). There were 74 students (30%) that demonstrated elevated levels in other perfectionism (Figure 6). Females (31%) outscored males (28%).

The social perfectionism category showed 112 students (46 %) scored moderate to elevated levels of perfectionism. Male students (53%) outscored female students (45%) (Figure 4). There were 71 students (29%) who scored elevated levels of perfectionism in social perfectionism category (Figure 6). Males (38%) scored higher than females (28%) in this category.

Students were also evaluated according to scoring high in all three categories of self-oriented, other oriented perfectionism, and social perfectionism. Scoring high in all three categories can cause added negative stress and clinical negative symptoms. There were 66 students (27 %) that scored moderate to elevated in all three perfectionism categories. Male students (38 %) scored higher than female students (25%). The study also showed that 29 students (12%) scores were elevated in all three categories. Males (13%) scored higher than females (12%) (Figure 5).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine maladaptive perfectionism among nursing students. The results showed a higher incidence of perfectionism among nursing students than the general population (30%). Cross and Cross [29] indicated that gifted children may feel increased pressure to perform stemming from themselves, parents, peers, and others. Perhaps many nursing students feel this same confining pressure.

These negative perfectionism results do not paint a positive picture for nursing students’ scoring on moderate or elevated levels, and maypresent obstacles to the learning process. All of these negative correlates may interfere with the learning process and perhaps increase student perceptions to do well. Not only does perfectionism affect the student’s ability to perform well in the classroom and simulation lab setting, but it also moves into the clinical setting, and may extend to future employment. Nurses have a reputation for “eating their young” and perfectionism may play into bullying.

6. Recommendations

Educators may be able to adapt curriculum to alleviate stressors of nursing students. Individual instructors need to also become educated on perfectionism, and then help students at risk by providing resources. Instructors should also become mindful on individual classes that may trigger perfectionism in students.

Students could also benefit by identifying perfectionism and subsequent counseling, or open discussion regarding their behavior [17,12]. Maladaptive perfectionism can be turned into a motivating healthy driving force for success. Ulu and Tezer [30] linked positive perfectionism to conscientiousness-nursing students’ self-defeating behaviors. Adaptive perfectionism has been linked to higher grade point averages for students [31]. Positive perfectionism has also been shown to raise satisfaction of life and increase self-esteem [17,32,33].

7. Conclusion

Nursing students show a higher incidence of negative perfectionist than the general population. Maladaptive perfectionism interferes with every aspect of an individual's life. Negative ramifications of perfectionism can interfere with the learning process and may enter into a nurse's career. It is beneficial for educators and students identify perfectionist tendencies and make adjustments to decrease stress and increase learning.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests with the work presented in this manuscript.