1. Introduction

The elderly population is growing rapidly in Japan, and care for the elderly is becoming one of the most important problems. It is considered important that elderly people are able to lead lives that are as normal as possible. Therefore, the prevention of dementia has become more important [1]. Many elderly people suffer from depression related to grief or loneliness. Thus, in health-care settings such as nursing homes and day care centers, “nonpharmacologic” approaches are being introduced to help maintain the mental condition of elderly people with dementia [2]. Nonpharmacologic therapies include music, reminiscence, art, and reality orientation therapies, and have been shown to improve quality of life (QOL) and prevent disability among elderly people. Among these therapies, horticultural activities encourage interaction between people and plants [3].

Recently, several studies have described the benefits of horticultural activities for elderly people with dementia, which include improvements in psychologic [4], physical [5], social [6], and cognitive [7] function. Based on these studies, participation in horticultural activities appears to represent a promising method for preventing dementia. However, it is difficult to generalize the results of these studies because of their methodologic weaknesses. First, the selection of study participants is challenging, because the diagnostic criteria for dementia remain unclear. Second, the intervention methods vary between published studies. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that a structured horticultural activities program could prevent dementia in elderly residents of nursing homes; that is, it would support cognitive function and daily activity in elderly people, and improve the QOL of both elderly people and their families.

2. Methods

This study was a controlled trial. The flow of the implementation method is shown in Figure 1. The Intervention Group followed the horticultural activities program, in addition to routine care, in a room separate from the usual care setting. During the intervention period, the participants cared for plants daily. The sessions lasted 30–40 min once a week for six consecutive weeks. In contrast, the Control Group received only routine care at the same institution as the Intervention Group for the same amount of time.

2.1 Participants

The participants (n = 9) were elderly residents of nursing homes. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- ≥65 years of age or older;

- No diagnosis of dementia by a physician;

- No speech or vision disorders; and

- No participation in other research studies.

Twelve patients met the inclusion criteria. The researchers explained the study’s objectives and methods and that the potential participants had the freedom of choice to participate in the study. After interviewing each patient and their families, nine provided informed consent to participate, forming the Intervention Group.

Demographic data, including information on favorite plants and any experience with plants and plant care, were obtained in advance from each participant and their families. Nurses and care workers assessed participants’ physical and mental health to determine whether they were willing and able to participate in the horticultural activities program. The Control Group was age- and gender-matched to the Intervention Group, and comprised elderly people residing on a different floor of the same nursing home. Members of the Control Group were assured that they would enjoy the same standard of care as participants in the Intervention Group.

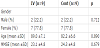

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is scored on a scale of 0–30 points [8], was performed before the study to provide a baseline evaluation. The distribution of participants is shown in Table 1. The Intervention Group comprised nine participants [2 men and 7 women; mean age (mean ± standard deviation), 89 ± 7.14 years] with a mean MMSE score of 23.11 ± 5.5 points. The Control Group comprised nine participants (2 men and 7 women; mean age, 82.22 ± 6.63 years) with a mean MMSE score of 24.33 ± 4.8 points. No significant difference was found between the Intervention and Control Groups at baseline in variables pertinent to the outcome measures, such as gender, age, and MMSE score (Table 1).

2.2 Intervention methods

The horticultural activities program was designed to support mental, behavioral, social, and cognitive aspects of well-being in elderly people [9,10] based on the theory of personhood in dementia of Kitwood and Bredin [11], which emphasizes the need for caregivers to adopt individualized methods in approaches to dementia care. The participants were divided into groups of three or four. During every activity, a specialist (author), care worker (facility staff), and research collaborator supported the groups.

The specialist had several years’ experience of caring for elderly people with dementia as a nurse, was trained in horticultural techniques, and performed the role of group leader. During each session, facility staff members were required to observe the behavior of each participant. The research collaborator evaluated the behavior of each participant. The basic session flow and schedule are shown in Table 2. It was necessary that the seed or plant material used had the following properties: “easy to germinate,” “easy to grow,” “suitable for the season,” “caused sensory stimulation” (seeds and plants of various sizes, form, color, and smell), and “well-known.”

2.3 Evaluation methods

The vitality, depressive symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), QOL, and cognitive function of the participants were evaluated. Vitality was evaluated using the Vitality Index (VI) [12]; depressive symptoms were measured using a set of 15 items termed the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) [13]; ADL was rated using a set of 20 items termed the ADL-20 [14]; QOL was assessed via a set of seven items in the 100-mm visual analogue scale [15]; and cognitive function was evaluated using the MMSE [8]. A total of two assessments were performed. GDS-15, QOL, and MMSE scores were evaluated by the researcher. Additionally, a care worker who knew the participants evaluated the behavior of each participant based on VI and ADL. Before the intervention, the author explained the evaluation methods to the facility staff to ensure reliability of the assessments.

2.4 Statistical analyses

The Student’s t-test and χ2 test were used for comparison of the two groups at baseline. To assess the effectiveness of the horticultural activities program, we performed two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance and the Bonferroni test. The statistical software IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The VI, GDS-15, ADL-20, QOL, and MMSE scores are shown in Table 3. Mean VI, ADL-20, and MMSE scores did not significantly change in either the Intervention or Control Groups. Mean GDS- 15 score in the Intervention Group significantly improved after the intervention (P < 0.05) relative to the Control Group. Regarding QOL, the mean score for the “satisfaction with life” subscale in the Intervention Group significantly improved after the intervention (P < 0.05) relative to the Control Group.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate the benefits of participation in a horticultural activities program on short-term depression and QOL in elderly people. Mean GDS-15 score and “satisfaction with life” significantly improved after the intervention. In a 3-month, onceweekly intervention (totaling 12 sessions), Sugihara et al. [16,17] reported an improvement in the GDS-15 score. In this study, a total of six sessions of the horticultural activities program were administered over a 1.5-month period. The term of this study was shorter than those previously described; therefore, our results, which indicate the efficacy of a short-term horticultural activities program on depression, are a new finding.

The significant improvement in the GDS-15 score evident in this study may be attributable to the fact that participants were able to take care of plants and share their experiences, such as deriving satisfaction in their growth and pleasure in harvesting their produce, with others. The physical activity of elderly people and their communication with others tend to decrease when living in a facility, resulting in decreased psychologic function. In this context, the improvement in GDS-15 score obtained in this study is of great significance.

In this study, the “satisfaction with life” score in the QOL subscale significantly improved after the intervention compared with that of the Control Group. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported a significant improvement in “satisfaction with life” score after horticultural activities in elderly people. In a previous 8-week study of horticultural activities, the life satisfaction score significantly improved after intervention compared with the Control Group [6]. In this study, the horticultural activities program was conducted for 6 weeks. Therefore, the study period was shorter than that of the previous study. The results of this study, which demonstrated the efficacy of a short-term horticultural activities program on QOL, constitute a new observation. The horticultural activities continuously provided a sense of responsibility in the daily care of plants. Additionally, the participants were able to eat and share their harvest with others. These factors may underlie the significant improvements observed in “satisfaction with life” score. Considering that with advancing age, people lose interest in their surroundings, the improvements in “satisfaction with life” score obtained in this study are of great significance.

The major limitations of this study were the small number of participants and the nonrandomized nature of the trial. Therefore, further, randomized controlled trials involving a greater number of participants are necessary to confirm the effects of a long-term horticultural activities program for elderly people.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of participation in a horticultural activities program on psychologic, physical, and cognitive function and quality of life in elderly people. In the Intervention Group, GDS-15 and “satisfaction with life” scores significantly improved after the intervention compared with the Control Group. These results indicate the ability of horticultural activities to improve short-term depression and satisfaction with life, and suggest that this program may be an effective treatment modality to improve depression and satisfaction with life in the elderly population.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

All the authors substantially contributed to the study conception and design as well as the acquisition and interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript.