1. Introduction

Child maltreatment is a major public health and social welfare problem around the world which can cause severe and long-term consequences for children’s subsequent adult lives. Despite growing awareness of child maltreatment in recent decades, great challenges remain in acknowledging children at risk of harm – and consequently there are children who do not receive support and protection.

Within the health care context, one challenge has been that nurses and physicians are often unwilling to report child maltreatment to the responsible authorities [1-3]. It has also been shown that nurses and physicians feel unsure when identifying child maltreatment [4-9] and feel unsure about the level of evidence required and fear making a report [3,9,10]. Other barriers to reporting have been linked to emotions such as anxiety, uncertainty and stress [4,9,11-13]. A lack of education and training among health care professionals is a repeated concern [3,6,7], and one study [11] found that general practitioners had received little training in child abuse issues compared with social workers.

Although there are a range of studies on barriers inhibiting health care professionals’ reporting, there is a lack of knowledge about how such barriers differ between health care professional groups. A previous study showed that professional group affiliation was the most significant factor behind hospital personnel’s decisions not to make reports [9]. Based on this finding, this article aims to explore and deepen the understanding of the differences between professional groups’ work with child maltreatment and the different conditions under which they have to perform such work. The research questions are as follows:

- What differences are there between physicians’, nurses’, nurse assistants’ and hospital social workers’ work experience, training, awareness or use of organizational support and experience of reporting?

- What differences are there between the professional groups regarding the extent to which a range of emotions and circumstances has ever affected their decision not to make a report?

- How may the differences between the professional groups be understood?

2. The Swedish Legislation and Definitions of Child Maltreatment

Sweden is often characterized as a social welfare state with a preventive and family-oriented child welfare approach, although it has been more common to describe the system as combining preventive welfare and protection functions [14-16]. One of the protective approaches is the obligation for all health care professionals to immediately make a report to social services when they suspect that a child may be at risk of harm, without the requirement of evidence [17,18]. It is social services’ responsibility to investigate incoming reports which may concern children in need of protection as well as in need of support.

In recent years, it has been clarified that employees with a suspicion cannot disclaim their responsibility to make a report by referring to someone else having committed to report [19], meaning that subordinated employees should not refer to a superior, or to another profession. This involves not only a degree of autonomy for all health care professionals in Sweden to act regarding this matter independently of other professionals’ opinions it is in fact an individual obligation.

Although there is a lack of nationwide data, the National Board of Health and Welfare [20] argues that there seems to be underreporting from health care professionals, as only 10 percent of the reports come from health care institutions. As a way to increase awareness of children who may be at risk, the National Board of Health and Welfare [19] released guidelines a few years ago with clearer descriptions of which situations should be reported to social services. The guidelines include all types of abuse, neglect and exploitation as well as serious relationship problems within the family, or witnessing or living in an environment in which violence or threats of violence are present. They also include when children and youth are at risk because of their own behavior, for example self-destructive behavior, criminality or misuse of alcohol or drugs. Further examples are children exposed to threats, violence or other forms of abuse by peers or others, and children with severe problems in their school situation based on social difficulties [19]. Clearly, there are a wide range of situations that may form the basis for reports to social services.

3. Data and Method

The professional groups selected for this study were physicians, hospital social workers, nurses, and nurse assistants; the latter group was chosen because they spend comparatively large amounts of time with children and their families in the various departments. Data was collected from the four largest children’s university hospitals in Sweden. Only personnel working in inpatient wards were selected, and they worked in a range of different departments specializing in emergency care, oncology, hematology, surgery, nephrology, neurology, cardiology, infection, gastroenterology, and endocrinology.

It was not possible to reach all personnel via their professional organizations, trade unions, or hospitals. Therefore, the results should be considered as a sub-set of those actively working at the time at which the study took place, with the aim of providing a varied and representative picture of the personnel’s understanding.

During the first stage, contact was made with the directors of the children’s hospitals. After their approval to carry out the study within the hospital, contact was made with the directors of the different departments and sometimes a contact person for a team of physicians or hospital social workers. About 100 such persons were contacted. In sum, 23 visits were made to different departmental or team meetings between April and June 2013. At the meetings, the project was presented, and the questionnaire was distributed, filled in, and collected. Because of time constraints at some meetings, these groups were provided with addressed envelopes to return the questionnaire later. One reminder was sent to departments which had received addressed envelopes. In total, 365 questionnaires were distributed, and 295 (80.8%) were correctly completed and returned.

72 physicians, 119 nurses, 70 nurse assistants, and 34 hospital social workers responded to the questionnaire. While the hospital social workers represent the total population in the hospitals quite well, because all were asked to participate, there is a weaker representation of the other professions because some individuals were not scheduled to work on the collection day, some were on leave, and so on.

An ethical application for this study was approved by Mid Sweden University’s Ethical Review Board [21]. The questionnaire was filled in anonymously and thereafter coded and added to a code list. Information about the study was provided in writing to the staff when the questionnaire was distributed and voluntary consent was obtained from all participants.

3.1 The questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed by the author, with inspiration from previous research and in dialogue with researchers in the field. It had two sections, and included 22 questions in total. For some of these, respondents were asked to choose a rating on a five-point scale, and for others they could choose from a list of between three and 14 alternative responses, some of which were open-ended. The first section asked for the respondent’s gender, age, profession, and work experience.

The second section asked how many reports the respondents had made, and if at any time they had had a suspicion they decided not to report, but afterwards felt that they should have done so. Further questions asked about the extent to which they agreed (on a five-point scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’) that they had obtained sufficient training in physical abuse, physical neglect, psychological abuse and neglect, and the extent to which they agreed that they were familiar with what the Social Services Act implies for their work. Some questions focused on organizational factors; whether they had knowledge about available routines and guidelines, a child-protection team, a children’s advocacy center, or another expert to consult when they suspected that a child might be at risk. The respondents were also asked to grade (on a five-point scale from ‘has not influenced at all’ to ‘has often influenced’) the extent to which 11 emotional factors (e.g. ‘feeling insecure about assessing the situation as abuse or neglect’) and circumstantial factors (e.g. ‘parents’ explanation about the injury’) may have influenced them not to make a report.

The questionnaire also included questions that have been analyzed in two other publications: One that describes the organizational and professional conditions and compares the awareness of organizational support between personnel at the four hospitals [22], and another which analyzes what characterizes high/low reporters and personnel’s decision not to report [9].

Since the questionnaire was constructed by the author, its validity and reliability had to be confirmed before it was used. Therefore it was pre-tested by two representatives of each selected profession, but not at the same children’s hospitals. The representatives were asked to fill in the questionnaire and leave comments concerning whether they thought the questions were relevant and understandable, and whether they could suggest any additional questions or other changes from their respective practical experience. This resulted in minor language clarifications and an additional question being added to the questionnaire.

3.2 Variables and Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS 22.0, and bivariate analysis, chisquare tests and binary logistic regression analyses were performed. Since professional affiliation is the focus of this paper, the four outcome variables are physicians, nurses, nurse assistants and hospital social workers, variables which were dichotomously coded into the particular profession/all other professions in the regressions.

Deciding not to report refers to a situation in which respondents had a suspicion which they decided not to report, but afterwards felt that they should have. This variable is dichotomously coded into ‘decided not to report’ (58.6% or 164 respondents answering occasionally or several times) and those who ‘never felt afterwards that a report should have been made’ (41.4% or 115 respondents). The five-point variables are dichotomously coded into ‘agree’/‘disagree’.

4. Results

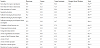

When exploring how the professional groups answered the questions about work experience, training, awareness or use of organizational support and experiences of reporting to social services, the findings show important differences. Nurses had the shortest work experience in the profession, as well as within their clinic (Table 1), which indicates a high rate of turnover among nurses.

Almost all nurses had their main education in Sweden, and among the professionals who had their main education abroad, four (physicians) were educated in other Nordic countries, 12 (nine physicians and one of each of the other professions) in other European countries, and one (hospital social worker) in Asia. Hospital social workers most often had at least one instance of specialist education besides their social work education, and 35 percent of them had a basic education in psychotherapy.

Four questions asked the extent to which they agreed that they had obtained sufficient training in the field of child maltreatment, and the findings show that a minority of the nurse assistants believed they had obtained insufficient training in all areas asked about, whereas nearly 60 percent of the nurses believed they had obtained sufficient training in the Social Services Act and were confident about what this legislation implies for their work. While all hospital social workers were confident about this legislation, close to 21 percent of the physicians were not confident about it. In general, a minority had obtained sufficient training in physical neglect and psychological neglect although slightly more than half of the hospital social workers believed they had obtained sufficient training within these areas.

The questions about available organizational support show more varied answers between the professional groups. While hospital social workers more often used supervision and mentors, and were more often aware of guidelines and routines and children’s advocacy centers, the physicians were more often aware of child protectionteams and the nurse assistants were slightly more often aware of other specialists at the hospital.

Table 1 show that it is exceptionally rare for nurses and nurse assistants to have made five or more reports, while almost half of physicians have done so, and nearly two thirds of hospital social workers. The findings further show that nine out of ten nurse assistants and more than two thirds of nurses had never made a report, while nearly 17 percent of physicians and 30 percent of hospital social workers had made 20 reports or more. It was also more common to have decided not to report despite having a suspicion, the more reporting experiences a professional group had.

As can be seen in Table 1, the variable ‘decided not to report a suspicion’ was not significant in this test. The questionnaire included another section of questions, however, which asked the respondents to grade the extent to which a range of emotions and circumstances had ever affected their decision not to make a report. In a previous publication, these factors’ effect on all the respondents was analyzed into a ranking scale [9], and the purpose here is to compute their joint effect on the respective professional group. The variables in Table 2 follow the ranking scale, meaning that ‘feeling insecure about assessing situation as abuse or neglect’ was the most common factor and ‘feeling too stressed to manage a report’ was the least common factor among the professional groups altogether.

Table 2 shows that even though ‘feeling insecure about assessing situation as abuse or neglect’ was the most common factor for all professions, a significant effect remains only for nurses when adjusting for all these factors for individual professional groups. It is 2.4 times more likely that someone who is insecure will be a nurse, while they have significantly lower odds of being a hospital social worker. Among those who are anxious about threats or their own safety, the odds of being a nurse are nearly 3.3 times higher1 . Although nurse assistants were the most affected by as many as eight factors [9], none of them were significant when adjusted for all eleven factors. However, two factors stand out from the others: ‘Young person’s explanation about the injury’ and ‘feeling anxious about threats or my own safety’ gives nearly two times higher odds of being a nurse assistant.

Those who feel anxious about destroying the relationship with parents have almost four times higher odds of being a physician, while feeling anxious about destroying the relationship with the young person and having been affected by the parent’s explanation about the injury gives two times higher odds of being a physician, although the latter two are not significant in this model. The most striking number in Table 2 shows that those who are trying to solve the situation themselves have almost six times higher odds of being a hospital social worker, which corresponds with what hospital social workers have expressed in an interview study [23].

5. Discussion

The findings show a general pattern that hospital social workers have received the most training in child maltreatment issues, are more often aware of organizational support (with the exception that physicians are more often aware of teams and nurse assistants are more often aware of other specialists), use supervision and mentors more often and report more often than the other professional groups. Additionally, hospital social workers are more likely to feel confident about assessing situations as abuse or neglect and trying to solve the situation themselves as an explanation for why they have decided not to report despite having a suspicion. After hospital social workers, physicians are the profession with the most training in child maltreatment issues, with the most awareness of organizational support, and the most experience of reporting. The main reason for their decision not to report is being anxious about destroying the relationship with parents, a finding that corresponds with the perception that physicians should be wary about notifying social services because patients should not be afraid to seek medical care [24]. After physicians, nurses had obtained more training in child maltreatment issues than nurse assistants, but in general had as little awareness of organizational support as nurse assistants, although they made slightly more reports than nurse assistants. The main reasons for nurses’ decision not to make reports were being uncertain about assessing the situation as abuse or neglect and being anxious about threats or their own safety, while none of the emotional and circumstantial factors were significant for nurse assistants when their joint effect was computed, even though a previous study showed that they were the most affected by as many as eight of the eleven factors [9]. The overall findings show that the more training and the more knowledge about organizational support a profession has, the more confident they are in making assessments and decisions, and the more experience they have of reporting.

One explanation may be that the length of the basic vocational training more or less determines the degree of knowledge about child maltreatment issues (physicians have five years, hospital social workers three and a half years and nurses have two and half years of higher education, while being a nurse assistant require studies at upper secondary school in Sweden). This does not explain, however, why nurse assistants are less aware of organizational support even though they have spent more years working at hospitals than the other professional groups. It can thus be argued that the findings should be understood with regard to the specific inter-professional relationships characterizing the hospital setting, namely the traditional medical hierarchy which is based on the expectations on physicians’ coordinating role in patient management and their formal responsibility for patient care [25]. Previous studies have shown that some nurses, nurse assistants, hospital social workers and physicians argue that physicians should have the responsibility to report [22,23,26-28]. The traditional medical hierarchy thus seems to have an important impact on perceptions of accountability and hence the work with child maltreatment within hospital settings. This means, in general terms, that the lower a profession’s status in the medical hierarchy, the less training and awareness the profession has about the supporting structures, which leads to insecurity and lower levels of autonomy and experience of reporting (Figure 1).

Although hospital social workers are shown to be the most trained and experienced in child maltreatment work in this study, they are not positioned at the top of the medical hierarchy in Figure 1. A large number of hospital social workers may use their training and professional autonomy in their work with children at risk of harm, but bearing in mind that some believe that physicians should be responsible and they sometimes decide not to report if a physician considers that there is not enough evidence [23], the medical hierarchy limits their professional autonomy when working with child maltreatment to some extent. This is even more evident for nurses, according to a literature review describing barriers that inhibit nurses’ reporting [3]. Although physicians and hospital social workers have higher levels of training in assessing child maltreatment, nurses and nurse assistants may have more opportunities to recognize signs of risk because they spend more time with children and their families on the wards.

Little is known about the impact of professional affiliation, professional status and medical hierarchies on child maltreatment work and reporting structures within health care settings. Although this study argues that such an impact exists, there is a need for further research which explores these questions and suggests strategies for various professional groups to become more autonomous and skilled in identifying and assessing child maltreatment.

6. Conclusion

This study argues that the medical hierarchy has an impact on hospital personnel’s work with child maltreatment, which is contrary to the individual obligation to report to social services when one has a suspicion. The physicians’ formal responsibility for patient care [25] as a fundamental part of health care settings is challenged by the need for increased autonomous decision-making among other professional groups regarding child maltreatment cases. Whether children in need of support or protection will be identified within health care settings is dependent on all personnel in patient care having enough knowledge and professional autonomy to acknowledge and speak for these children.

If promoting individual accountability for at-risk children and adequate reporting processes, the educational and health care institutions need to emphasize more education and training in child maltreatment and the legal framework. This study contributes knowledge about how different barriers inhibit different professional groups’ assessment and decision-making, knowledge that may develop their specific vocational training. But joint training and case assessment in promoting multidisciplinary learning, structures and assessments are also crucial. Regular multidisciplinary team meetings on wards and discussing biopsychosocial concerns and potential risks to children may be ways to identify children at risk. It is important that all professional groups who are mandated to report suspicions to child protection services are involved – otherwise their observations might not be heard and adequately assessed, with the consequence that children at risk might be missed.