1. Introduction

The effect of migration on the risk for depression and pregnancy during adolescence is not well understood. This lack of information becomes even more obscure for populations who migrate to the United States. Limited research exists documenting the experiences and prevalence of mental health problems among immigrant Latino adolescents. However, much less is known about adolescents who migrate.

The current U.S. census indicate that one in five children and adolescents are immigrant [1], with approximately 41% of Mexican origin [2]. Migration to the US continues with increasing rates among adolescents and women. There is a need to study and understand risk depression, pregnancy, and access to health care in this population with the increasing rate of their migration from Mexico to the United States.

The leading cause of disability among adolescents globally are depressive disorders [12,13]. Adolescent depression and pregnancy are the two most significant problems affecting adolescent health in the Americas [3] with increasing rates in Mexico and the U.S. Affective disorders, including major depression, have been associated with risky sexual activity among adolescent girls.

Adolescent pregnancy is a risk factor that negatively impacts the development of both mother and infant, the quality of the mother/ infant relationship, and their overall health. Pregnancy also has a long-term negative impact on an adolescent’s achievement of their potential. Over 16 million adolescents 15 –19 give birth every year globally, accounting for 10% of all births [14].

Little is known about the migration of women and girls from Mexico to the U.S., study.. What is known is through the migration lens of their parents or other family members. However, from the little that has been documented, we know that this population is unique in terms of their experience and the effects they display from migrating. Migration research has been narrowly based on quantitative data analyses with the study of youth a minor data point, lacking differentiation of generations, gender, migration stage, or its impact on mental and reproductive health, especially among adolescent girls [8-11].

The high risk for sexual abuse and violence places these girls at risk for STDs, including HIV, and a range of post-traumatic stress disorders associated with sexual violence. In general, the mental and reproductive health needs of these young girls often go unnoticed and unprotected. Even in well-organized health care settings, the lack of sensitivity from medical personnel to the needs of immigrant women from other cultures that differ from host countries is often more pronounced in migrant contexts than it is in general.

Health policies have been developed in silos and rarely integrate factors that affect migrant/immigrant adolescent girl’s mental and reproductive health. Binational policies have focused on either public health threats to the U.S and Mexico, or social justice issues like occupational, interpersonal, social, or discriminatory risks [15]). With poor coordination and frequent contradictory health policy goals, mental and reproductive health risks have been exacerbated and not prevented.

Available research on this topic is usually based on either cross sectional or longitudinal studies. In general, cross sectional studies have supported a relationship between depressive symptoms or disorders and sexually risky behavior [4,5,6]. Longitudinal studies have also determined that depressive symptoms are associated with earlier onset and more persistent patterns of risky sexual behavior among adolescents in urban and rural settings [7,5]. None of the existing studies draw upon qualitative methods or comparison groups.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the migration experience of Mexican origin adolescent girls aged 14 – 17 and its impact on the depression and pregnancy rates both in Mexico and in the United States. Questions guiding this study were: What is their mental and physical health status during these stages? What risks do they undergo? Is there a greater risk for depression and pregnancy among those who migrate compared to those who do not? Do particular needs exist for health care and access during certain stages of the migratory process than other stages? Additionally, this paper focuses on the methodological approaches to conducting Community-Based Participatory Action Research (CBPAR), particularly focusing on sensitive topics such as migration, depression and teenage pregnancy. The findings of this study, along with community guidance and input were utilized to design a culturally based intervention focused on addressing depression and teenage pregnancy.

2. Gaining Entry

This study employed a Community-Based Participatory Action Research (CBPAR) approach to develop and adapt the intervention. CBPAR is a methodology that engages community members as research partners in order to identify health issues in the community [16]. The CBPAR approach that set the stage for this study began with the initial engagement stage in the comparison site of the Niños Sanos, Familia Sana (NSFS) study [17]. The engagement process in the comparison site of the NSFS study consisted in the collaboration of community members to develop psycho-educational workshops [18]. The community-based approach implemented in the comparison site engaged community members and local stakeholders in the identification of the workshop topics. The community-based approach implemented the Cultural Adaptation Process [19] and the Ecological Validity Model [20]. Through the three phases of the CAP, the researchers, in collaboration with the community members and stakeholders, were able to identify and adapt the workshop topics. The EVM helped in culturally-adapting the delivery method of the workshop content. The community-based approach to the development and delivery of the workshop proved to be effective for workshop attendees. More specifically, the workshop evaluations indicated that participants were satisfied with the content of the workshops and presentation style [18].

The use of the CBPAR approach to engage study participants and community members in the comparison site along with the CAP and EVM proved to be effective in engaging community members. More specifically, this approach allowed for researchers to collaborate with community members and stakeholders by integrating the existing strengths and assets that exist in the community. By acknowledging and integrating the community’s strengths and assets, the NSFS research team was able to foster a relationship of trust with the local community. This approach also increased the acceptability of university researchers in the community as research partners. It resulted in workshops discussions were participants began to identify the need for additional projects in the community. One of the major themes that emerged from these discussions was the need to address mental health issues for youth. These discussions and the established relationship between NSFS researchers and community members facilitated the entry of the DESPIERTA study research team.

To maintain the established trust and collaboration that was fostered through the community-based approach of the NSFS study, the DESPIERTA team also worked collaboratively with community members in the different stages of the research process. In the initial stage, it was important for the DESPIERTA principal investigator to work closely with the NSFS research team as a way to gain entry and begin to foster trust with the community. Aligned with the CAP, the principal investigator joined the NSFS as the change agent who would be leading the DESPIERTA intervention. Because the NSFS had been working with the community for more than five years, and some of the NSFS research members were originally from the community, they served as the opinion leaders who facilitated the fostering of community relationships and the collaboration between the DESPIERTA researchers and the community.

3. Parent Communication Study

An initial stage of the study was to conduct focus groups in the community to explore the needs. Focus groups were facilitated in Spanish and were conducted in an effort to explore parents personal attitudes, social pressures, challenges and facilitators of parent/ adolescent intent in addressing sensitive topics with their children. Sensitive topics identified in this study were pregnancy, school dropout and substance abuse. Through a qualitative methodology and utilizing the Theory of Planned Behavior [21], TPB, the experiences and the beliefs of participants was explored. Findings from this study pointed to the parents perceived expectations to guide teens behavior in regards to (1) morality, (2) honesty, (3) family trust, (4) respect for parents, (5) reverence for family unit, and (6) family love. Furthermore, parents stressed the importance of communicating with their children in regards to sensitive topics.

Prior to data collection, several meetings took place with local stakeholders to share the purpose of the study. After letters of support were obtained from and study was approved, community members were hired to assist with research activities. The participation of community members from the community was instrumental to the success of this research study as topics addressed are of high sensitivity in the Latino community.

3.1 Despierta: Part I

Following the communication study with parents and with the guidance from the community, research with teenagers followed. The Despierta study focused on investigating the migration experience and its impact on the depression and pregnancy rates among 14 – 17 year old girls of Mexican origin adolescents both in Mexico and the United States. Through the employment of a mixed methodology using both a qualitative and quantitative approach, this study explored and compared risk for depression, pregnancy, and access to care.

As done prior, meetings took place with stakeholders to ensure support for the study to take place. Stakeholders included community members in the health and education fields. Again, a community member was hired to aid with data collection. Female college students were recruited and trained to conduct focus groups. Data collectors were close in age to participants and were also from their same cultural group and had prior familial histories of migration.

Depression became on of the dominant themes in the focus groups. The CEDS (10 point scale) was not able to fully capture the prevalence of depression with participants. However, the focus groups provided a rich source of data where participants were able to disclose symptomatology and incidence. Furthermore, findings identified to the need for administering a full scale depression questionnaire (CEDS 20) in an effort to capture depression fully among participants.

4. Method

4.1 Study design

This was an exploratory descriptive mixed method design integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches. While the research process was combined in both countries, including ethnographic methods, independent data collection and management occurred separately.

4.2 Setting

Participants were recruited from California’s Central Valley in a town named Valle del Sol (pseudonym). Located in one of the poorest Congressional Districts in the United States, Valle del Sol is primarily a low-income agricultural community. Monthly median household income is $2,180, which is about 42% lower that the California state household average. Currently, the town has only one qualified health clinic. Most participants rely on public transportation to commute to and from school.

4.3 Sample

Study participants consisted of Mexican-origin adolescent girls aged fourteen to seventeen living in Valle del Sol. A convenience sample of 58 Mexican-origin migrant adolescent and young adult girls were included in the sample. The 58 participants in Valle del Sol had a personal or familial history of migration from Mexico.

4.4 Demographic information

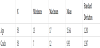

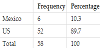

Participants included 58 females (N=58) from the Valle del Sol community. Table 1 summarizes their sample demographics, and Table 2 summarizes their birthplace. The average age of the 58 participants was 15.64 years, and their average grade level was 10th grade. More than 89% of the 58 participants were born in the U.S., and the rest were born in Mexico.

4.5 Instruments Utilized

Six different instruments measured the variables of interest (Physical status, Mental Health, Self Efficacy, Risky Behavior, and Access to Health. Each instrument must be described with a sample question and how it is answered, range, yes or no. Following is a list of the instruments utilized

- Physical health status was assessed through the National Health Interview Survey [22],

- Mental health status, was assessed through the CES-D 10 item scale

- Self -efficacy was measured with the Self-Esteem scale developed by [23],

- Health seeking behavior scale,

- Risk taking behavior was measured through the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior questionnaire, lastly

- Access to health care was assessed through the use of the National Health Interview Survey developed by Simpson.

5. Results

This study was guided by the following research questions: What is their mental and physical health status during these stages? What risks do they undergo? Is there a greater risk for depression and pregnancy among those who migrate compared to those who do not? Do particular needs exist for health care and access during certain stages of the migratory process than other stages? To answer these questions, a mixed methodology using principles of CBPAR were employed.

5.1 Quantitative findings

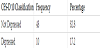

In our analysis of the access to health care, only 12.1% of the participants indicated that they have a regular health care provider. Of the total participants, 81% indicated their primary source of health care to be a federally qualified health center. However, 81% of the total participants also indicated they had not seen a health care provider in the last 12 months. Almost 90% of the participants indicated that they have gone without health care during a time when they need it. Similarly, 89.7% of the participants indicated that there was instances that were too embarrassing or uncomfortable to discuss with their health care provider. Results from the CES-D 10 indicate that 17.2% of the participants were depressed (Table 3). Similarly, only 13.8% of the participants exhibited high risky behavior as assessed by the YRBI. Furthermore, only 10.3% of the participants exhibited low selfesteem.

5.2 Qualitative Findings

Qualitative Analysis led to the following needs. Through a CBPAR methodology, participants identified the following two needs, which will become the next steps for this research study. First, participants identified a desire to have meaningful conversations with their fathers about sexual health. Secondly, participants expressed a desire to find ways to educate parents about having honest and meaningful conversations with their children about sexual and reproductive health.

5.3 Meaningful conversations with their fathers

Most research has looked at the effect and preventive measures from mothers speaking to their daughters in regards to pregnancy prevention and sexual health. The importance of mother -daughter conversations in regards to these topics are important and vastly documented. Through a gendered analysis, existing research has been able to document the meaningful conversations between females. There is a dearth in literature pertaining to effective teenagers having father-daughter communication and education in regards to sexual health with their parents.

Juanita expressed, “I want to be able to ask my dad questions about the things boys say.” Juanita has identified that there are certain topics she would like to discuss with her father to vet the validity of such claims. “A boy will say ‘if we do this, you won’t get pregnant’ I want to know if it is true” shares Jessica. We are able to conclude through Jessica that conversations about pregnancy prevention are also happening with her sexual partner

5.4 Educate parents about having conversations with children about sexual health

Participants identified the need to educate their parents about how to have conversations with their children. Furthermore, participants recognized that their parents are not equipped with the tools to engage in conversations that are culturally taboo, such as sexual health and depression. Anna stated “I asked my mom if you can get an STD from kissing, she responded ‘ask your teachers, don’t they teach you anything at school?’ I could tell she was embarrassed.” In this example, Anna took the courageous act of initiating a conversation with her mother about the transmission of STDs. However, as recognized by Anna, her mom was embarrassed to discuss the topic. This stems out of a cultural taboo to talk about the topic. Furthermore, Anna’s mom believes that these are conversations that should be taking place at school. Anna’s mom then goes on to question what is being taught in school.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the migration experience and its impact on the depression and pregnancy rates in Mexico and the United States of Mexican origin girls aged 14-17 through the use of Community- Based Participatory Action Research methodology. The findings of the study and primarily through community input were utilized to design a culturally based intervention. Quantitative analysis identified that the majority of the girls, 81% had access to health care. However, during the previous twelve-month period the majority of them indicated that they not only did they not see a healthcare professional, but they went without health care when needed. Furthermore, the majority also indicated that they were too embarrassed to discuss health needs with their healthcare provider. The qualitative data underscores their embarrassment in communicating their critical health care needs. For example, the instances when the participants indicate the need to be able to discuss with their parents about sexual health could reflect their limited or lack of sex education and access to reproductive health care. Furthermore, this it could also identify their need and desire for knowledge about sexual and reproductive health. Need to integrate with literature from other similar research. Discussion should continue with subsection on each variable and what the findings indicated compared with other similar research in the background.

6. Implications for Nursing

A need exists to adapt effective or create new preventive binational interventions that nurses and other health professionals can deliver in a culturally appropriate manner. Community Based Participatory Research is a method that engages community partners, researchers, and health care providers. CBPR is regarded as a valid approach to disease prevention and health promotion by focusing on understanding and building upon underlying mechanisms associated with peoples’ behaviors, responses to life experiences, and cultural histories experiences before developing preventive interventions to improve health outcomes [12]. CBPR benefits both the community participants under study, and the scientific community. In the 21st Century it is essential that professional nursing build on the knowledge that the cultures of the world provide, and integrate what is learned through CBPR in clinical interventions. Such care must continue to evolve as it is guided by the cultural lens, values, and health beliefs of diverse populations. CBPR findings can also inform health systems, educational curricula for the next generation of nurses as well as and health policy concerning the need to address the mental and reproductive health needs of adolescent girls who migrate.

7. Implications for Future Research

7.1 Despierta part II

Findings from the prior study, pointed to the failure of the original CEDS scale (10 items) to fully capture the prevalence and severity of depression among participants. As a result, participants in prior study were administered the full CEDS scale (20 item scale) to garner a fuller understanding of the depressive symptoms displayed by participants and address the mental health needs of participants.

7.2 The need to address gap in design and testing for culturally adapted intervention

Through focus groups, participants identified the need to increase parent-teen communication. From quantitative data we found the need to increase health care utilization in the community and to create an environment where participants feel safe to access the health care resources and discuss their needs with health care providers. Need exists for intervention that promotes access to reproductive health knowledge and care.

A need exists for an intervention has been d culturally adapted, and collaboratively design with parents and adolescents, a feasible and acceptable parent/adolescent peer education prevention program. Furthermore to increase parent/adolescent communication in regards to contraception (abstinence - condom use), and decrease adolescent risky behaviors, depression, and pregnancy through the continual use of CBPAR methods.

8. Conclusion

Data is needed to guide binational health policies that will promote mental and reproductive health for teens on both sides of the border during migration. Knowledge on these prevalent issues is needed to understand girls experiences during the various stages compared to those who do not migrate.

In adapting interventions and through the use of CBPAR methods it is critical to engage communities in all stages of the study.

The community at hand possesses expertise into the contextual factors affecting communities and as such should be regarded as critical contributors to the study.

As shown in this paper, it is important to conduct exploratory CBPR pilot studies to gain insights into the community, become familiar of the community needs and increase community participation for the intervention.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.