1. Introduction

The declining birth rate is a major social problem in Japan [1]. A longitudinal study indicated that increasing the amount of time that fathers spend on childcare and household chores could help improve the birth rate of second children [2]. Currently, Japanese fathers with a child younger than 6 years of age spend an average of 1 hour and 6 minutes on childcare and household chores per day [3]. This figure is very low compared to fathers in Western countries. Consequently, the Japanese government has set a goal to increase the amount of time fathers with a child younger than 6 years of age spend on childcare and household chores to 2 hours and 30 minutes per day by the year 2017 [4].

In Japan, there are many educational programs that fathers can participate in, most of which are implemented during pregnancy. The principal aims of existing prenatal classes are maintaining a safe and comfortable pregnancy and childbirth and practicing childcare [5]. However, it is unclear whether these programs are effective in promoting fathers participation in childcare and household chores. Furthermore, intervention studies have not been performed with the goal of increasing the amount of time that fathers spend on childcare and household chores [6]. Thus, we developed an educational program to promote fathers’ participation in childcare and household chores [7]. A pilot study using the developed program was conducted to examine the most effective period of intervention [8]. The time that fathers spent on childcare and household chores was compared among three groups (a prenatal intervention group, a postpartum intervention group, and a control group). The pilot study revealed that fathers in the postpartum intervention group spent the longest time on household chores; therefore, we concluded that the program was most effective when introduced after childbirth.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effects of our educational program designed to promote first-time fathers’ participation in childcare and household chores.

2. Methods

This study was a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. The study period was from August 2012 to April 2013. The trial profile for this study is shown in Figure 1. From August 2012 to January 2013, 71 participants were recruited from fathers who took part in a prenatal class at one hospital. Fathers who participated in this prenatal class accounted for 34% of all deliveries at this hospital during the recruitment period. In the prenatal class, information concerning preparation for hospitalization and the process of childbirth was provided to the fathers. The number of fathers per class ranged from two to 11 people; therefore, participants were recruited from 21 classes in order to meet the required sample size.

Participants were assigned by block randomization to either an intervention group or a control group. One prenatal class was treated as one block. Randomization was performed by the research assistants using the envelope method as the allocation concealment mechanism. There were no participants who were not assigned to a group.

2.1 Participants

The effect size (ES=0.86) was calculated from the results of the pilot study [8]. The sample size required for a 5% significance level on a two-tailed test of significance and an 80% statistical power was calculated, resulting in a necessary sample of 21 fathers in each group. After factoring in the dropout rate of the pilot study (22.7%), the total number of required participants was 52.

The participants were first-time Japanese fathers 20 years of age or older. Exclusion criteria for fathers were unemployment, separation from their child, and participation in other educational programs. Exclusion criteria for children were having a physical disability or other severe illness, a birth weight of less than 2,500 g, or having an Apgar score of less than 6. A total of 71 fathers were recruited and 57 were included in the baseline assessment after meeting the inclusion criteria and agreeing to participate in the study (intervention group=28, control group=29). First follow-up assessment was conducted 1-weekafter discharge. Second follow-up assessment was conducted 1-month after childbirth. A total of 48 fathers completed questionnaires (intervention group=24, control group=24).

2.2 Intervention methods

We developed an educational program following program development procedures suggested by Chinman et al. [9].The design of the educational program is shown in Table 1. The educational program was divided into three segments. In the first segment, the importance of childcare and household chores performed by fathers was explained. In the second segment, information about childcare and household chores was provided, with the lecture emphasizing that mothers want fathers to help with household chores. In the third segment, fathers were given the opportunity to practice childcare techniques. The educational program took approximately 60 minutes to complete. The intervention was conducted once between the 1st and 5th day after childbirth. The researcher conducted all interventions with each father individually in a counseling room on the maternity ward of a hospital, where the participants’ babies were delivered. We recorded the time required for the intervention and confirmed that all interventions were conducted in accordance with the time schedule.

2.3 Evaluation methods

The measurement tool was a self-administered questionnaire consisting of demographics and variables relating to the amount of time spent on childcare and household chores. All questionnaires were completed anonymously.

The demographic data collected were as follows: age of the participant, information about family structure, and work hours and schedule. Participants also provided information about the gestational week at delivery and the child’s birth weight.

The primary outcome measures were the amount of time fathers spent on childcare and household chores. Measures were based on the 2008 Annual Population and Social Support Survey, which was a national survey on family life [10]. The participants were asked about the amount of time they spent on childcare and household chores on weekdays and the time was recorded in minutes. We asked the following question about childcare: “We would like to ask about your allotment of time for childcare. Please write the amount of time that you spend with your child, such as bathing the baby, putting them to bed, changing their diaper, etc.” The amount of time spent on childcare was assessed only in the follow-up questionnaire.

The secondary outcomes were acceptance of the father’s role in childcare role and household chores, confidence in childcare ability, and sense of burden related to childcare. Secondary outcomes were evaluated using a visual analogue scale [11]. Participants marked their answer on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100 millimeters.

2.4 Analyses

The demographics of the intervention and control groups were compared using the Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact test. A two-factor repeated measures analysis of variance was performed to compare the amount of time spent on childcare and household chores in both the intervention and control groups. Dunnett’s method was used for multiple comparisons of changes within the groups. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0. The significance level was set to equal or less than 0.05.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethical review boards of the authors’ institutions and the research hospital. Study participants in both groups received verbal and written explanations of the details of the study,including the purpose of the study and measures to protect privacy. In addition, the participants were informed that participation in, and withdrawal from, the study was voluntary, and that all data collected would be presented at academic conferences and published. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

3. Results

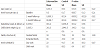

The demographic details of fathers who participated in the study are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were found in the baseline demographics between the intervention and control groups.

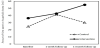

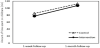

Comparison of the amount of time spent on household chores between the intervention and control groups is shown in Figure 2. The time spent on household chores significantly increased in the intervention group (Baseline, 36.3±29.0;1-month follow-up, 55.0±21.1; p<0.05).The time spent on household chores tended to be longer in the intervention group compared with the control group (p<0.10). Figure 3 shows a comparison of the amount of time spent on childcare. No significant differences were observed in the time spent on childcare between the intervention and control groups.

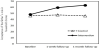

Comparisons of the secondary outcomes are shown in Figures 4-7. There was a significant difference in acceptance of the father’s role in household chores between the intervention and control groups (p<0.05). Acceptance of the father’s role in household chores significantly increased in the intervention group (Baseline, 48.3±20.0; 1-week follow-up, 59.6±21.6; p<0.05, 1-month follow-up, 63.4±23.6;p<0.01). No significant differences were observed in the time spent on childcare between the intervention and control groups.

Comparisons of the secondary outcomes are shown in Figures 4-7. There was a significant difference in acceptance of the father’s role in household chores between the intervention and control groups (p<0.05). Acceptance of the father’s role in household chores significantly increased in the intervention group (Baseline, 48.3±20.0; 1-week follow-up, 59.6±21.6; p<0.05, 1-month followup, 63.4±23.6;p<0.01). No significant differences were observed in acceptance of the father’s role in childcare between the intervention and control groups. Confidence in childcare ability tended to increase in the intervention group compared with the control group (p<0.10). Confidence in childcare ability significantly increased in the intervention group (Baseline, 49.0±26.5; 1-month follow-up, 62.0±21.1; p<0.05). The sense of burden related to childcare decreased in the intervention group and increased in the control group; however, the differences were not significant.

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate the effectiveness of our educational program to promote first-time fathers’ participation in household chores. The educational program used in this study increased the amount of time that fathers with 1-month-old babies spent on household chores. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported that an educational program significantly increased fathers’ participation in household chores. Therefore, the results of the present study are new findings.

In addition, acceptance of the father’s role in household chores significantly increased in the intervention group. The participants in the intervention group were provided information about the importance of fathers performing household chores, as well as information about childcare and household chores. We believe that these methods contributed to the observed increase in the fathers’ acceptance of their role in household chores. In fact, a previous study indicated that the higher the acceptance of the father’s role in household chores, the more frequently fathers participated in household chores [12].

However, the present study did not show a significant difference in the amount of time spent on childcare between the intervention and control groups. Intervention studies by Bryan [13] and Doherty et al. [14] reported that lectures focused on clarifying the father’s role in childcare increased the amount of time that they spent on childcare. We assumed that our intervention had no effect on childcare because the participants in both groups were already aware of their role in childcare before childbirth since all were enrolled in a prenatal class. Thus, it is likely that they learned about pregnancy and supporting the mother during delivery when they attended the prenatal class— in other words, the participants’ recognition of the father’s role in childcare was perhaps already developed before our intervention. On the other hand, it appears that other factors influenced time spent on childcare; for example, the frequency of support from extended family members and the rate of breastfeeding. However, we did not examine other confounding factors in the present study.

5. Study Limitations

In the present study, three participants in the control group were lost to follow-up, whereas none were lost to follow-up in the intervention group. This difference may have occurred because participants in the intervention group had a higher level of awareness of participating in this study. Furthermore, because this was not a blind study, fathers in the intervention group might have guessed that the study focused on the amount of time they spent on childcare and household chores, and this could have influenced their engagement in these activities. Finally, all participants in the present study were enrolled in prenatal classes and may have already had some level of recognition of the father’s role in childcare and household chores; therefore, the degree of effectiveness of our educational program among fathers who have not participated in prenatal classes is unknown and caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. Future studies should include fathers who have not participated in prenatal classes as subjects.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of an educational program designed to promote first-time fathers’ participation in childcare and household chores. The amount of time spent on household chores significantly increased in the intervention group. In addition, acceptance of the father’s role in household chores and confidence in their childcare ability significantly increased in the intervention group. These results indicate the efficacy of this educational program to promote first-time fathers’ participation in household chores.

In the clinical setting, it is desirable for nurses to perform postpartum classes for fathers while the mother and child are in the hospital. Since the program used in the present study could increase the amount of time fathers spend on household chores, we expect it to promote participation in household chores among first-time fathers.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Yamaguchi, S substantially contributed to the study conception and

design as well as the acquisition and interpretation of the data.

Sato, Y was involved in revising the manuscript critically for important

intellectual content.

Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank fathers who took part in this study, as well as the hospital staff who allowed the study to be implemented. The study is part of a doctoral thesis submitted to Yamagata University.