1. Introduction

In this study, we aimed to clarify clinical nursing competency with respect to caring for Hansen’s disease survivors at the final career stage of nurses’ development in Japan. The significance of this study can be summarized with respect to three key aspects.

First, Hansen’s disease typically occurs in developing countries, for example, India, Brazil, and Indonesia [1], and approximately 200,000 patients are newly diagnosed each year. In developed countries possessing high-level medical and hygiene systems, new cases almost never occur. In Japan, Hansen’s disease was diagnosed until 1950, and those patients are now aging. There were 1,840 individuals with the disease in 2014 living in thirteen national sanatoriums, with an average age of 83.6 years. We estimate that most survivors will be deceased in the next decade, and the history of Hansen’s disease treatment in Japan will end. However, we must protect its memory from fading with time and share its history. Conceptualization of clinical nursing competency with respect to the treatment of Hansen’s disease will contribute to the sharing of information in the future.

Second, with respect to the course of Hansen's disease, Mycobacterium leprae increases within macrophages and Schwann cells, and causes pathological changes at the nerve trunk and peripheral nerve palsy. Even when Mycobacterium leprae die out completely in the body, multiple severe sequelae, for example, loss of eyesight and dismemberment can remain [2]. Victims of Hansen’s disease have long been subject to stigma, discrimination, and prejudice worldwide, because of their appearance [3]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the characteristics of care for Hansen’s disease survivors, in order to meet their needs.

Previous studies in this area have been directed at prevention in developing countries [4,5] and stigma [6]. In Japan, there has been research on patients’ past experiences, for example, Araragi [7]. However, to our knowledge, there has been no research on clinical nursing competency for the care of Hansen’s disease, only on aging and activities of daily living [8]. Our study will also contribute to understanding within developing countries experiencing new diagnoses.

Third, Katsuyama [9] summarized the five stages of nurses’ career development process: becoming a nurse, developing as a nurse, hitting the wall, making more progress as a nurse, and handing down skills. The fifth phase refers to expert nurses who become role models for young nurses. Thus, in order to hand down knowledge, we need a conceptualization of clinical nursing competency for Hansen’s disease survivor nursing.

Clinical nursing competency has been conceptualized on multiple occasions. For example, Matsutani [10] reviewed 30 English manuscripts and identified three constructs and seven dimensions: 1) the ability to understand people (the ability to apply knowledge, and develop interpersonal relationships); 2) practicing people-centered nursing (providing nursing care, ethical practice, and professional relationships and management); and 3) ensuring quality of nursing (professional development and ensuring quality nursing care). Takase [11] completed a concept analysis of 60 English manuscripts and identified the following attributes of clinical nursing competency: individual aptitude, specialized attitudes and behaviors, and care based on expert knowledge and skills. Schwirian’s Six-Dimension Scale of Nursing Performance Japanese Version (6-D) [12,13] was constructed by interpersonal relationship/ communications, critical care, leadership, teaching/evaluation, and professional development. Nakayama’s Clinical Nursing Competence Self-Assessment Scale (CNCSS) was constructed to include 12 dimensions, and the correlation coefficient between the 6-D and the CNCSS was .762 (p < .001). Thus, the CNCSS was added, to ensure quality and risk management, as a new dimension to 6-D.

Nurses within Phase 5 according to Katsuyama’s definition can be called expert nurses. However, competency of expert nurses is specialized within a specific field and is difficult to apply within another field. Therefore, even expert nurses return to being beginners outside of their area of expertise [14]. The previously described studies demonstrated universal and typical concepts of clinical nursing competency, but did not identify concepts within specific fields. Therefore, conceptualization of clinical nursing competency for care of Hansen’s disease survivors will clarify the unique aspects of Hansen’s disease nursing, and the universality of nursing as a whole.

The purpose of this study is to clarify clinical nursing competency of care for Hansen’s disease survivors at the final career stage of nursing development. Thus, the significance of the findings will be with respect to: 1) sharing nursing competency information in Japan, where Hansen’ s disease treatment is ending; 2) applying this information in countries where the disease is still being diagnosed; and 3) clarifying the unique aspects of Hansen’s disease care and universality of general nursing.

2. Method

2.1 Research design:

A qualitative and inductive method was employed.

2.2 Definition of terms:

Clinical nursing competency: The main skills and abilities needed to practice nursing ethically and synthesize knowledge and skills effectively in unique situations or contexts [10].

2.3 Subjects:

All nurses’ years of employment at B Hansen’s disease sanatorium in Japan were distributed as follows: more than 20 years (20%), from 10 to 20 years (22%), and less than 10 years (58%). Therefore, nurses who had more than 20 years of experience working at B sanatorium were identified as being in the final career stage of nursing development and were chosen to serve as study participants after agreeing to participate. The unit chief did not participate because she did not offer direct care. In this study, nurses included both registered nurses and assistant nurses, because the government had established an assistant nursing school in the sanatorium in 1947 (now closed), and had employed assistant nurses. Assistant nurses can become registered nurses if they attend nursing school. In Japan, becoming a registered nurse requires attendance at nursing school, junior college, or university after graduating from high school, and it is a national qualification. Becoming an assistant nurse requires attendance at assistant nursing school after junior high school, and the license is registered by the Prefectural Governor.

2.4 Data collection:

A semi-structured interview was employed. An interviewer (the researcher) listened to and empathized with the subjects’ accounts. Questions were sometimes added in order to clarify meaning. Subjects’ accounts were recorded and verbatim transcripts were created with their permission.

2.5 Interview guide:

Nurses were asked the following questions with respect to the care of Hansen’s disease survivors: 1) What do you think are the important aspects of care? 2) How do you polish your skills? 3) What kind of clinical judgment is required? 4) How do you understand survivors? 5) Do you feel sadness or delight?

2.6 Data analysis:

Qualitative and inductive analysis were performed as follows, to understand the meaning behind the perspectives of the subjects. 1) Individual analysis: a) reading the verbatim transcript thoroughly, identifying reports about clinical nursing competency, and expressing the meaning in one sentence; b) grouping sentences with similar meanings, expressing the meaning of all the grouped sentences, and creating labels. 2) Whole analysis: a) reading all labels thoroughly, gathering similar labels, expressing the meaning, and creating categories; b) continuing these processes, heightening the abstraction level, and creating subcategories and categories. 3) Ensuring authenticity and validity of results: a) during the research process, supervision by a qualitative researcher; b) confirmation from subjects about whether categories and subcategories correctly captured their meaning.

2.7 Ethical considerations:

Subjects were told that participation was voluntary, data were kept confidential and used only in the study, and that they were free not to answer questions or provide information. The research objectives and procedures were also described to the subjects. Consent was obtained from all subjects orally and in writing. The research proposal was approved by the ethical committee at the National Sanatorium Oshima-Seisho-en (Authorization number: H24-1).

3. Results

3.1 Subject characteristics

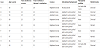

Subjects were nine nurses, all female, with an average age of 48.7 years, and an average number of years working at Hansen’s disease sanatorium of 26.3. Six registered nurses and three assistant nurses participated (Table 1).

3.2 Clinical nursing competency of care for Hansen’s disease survivors in the final career stage of nurses’ development in Japan:

Based on the verbatim transcripts, 105 codes were created and integrated into 5 categories and 19 subcategories (Table 2).

3.2.1 Ability to reduce multiple severe sequelae that are characteristics of Hansen’s disease and deuteropathy

This category shows that nurses possessed special skills for reducing multiple and severe sequelae of Hansen’s disease.

It contained six subcategories: a) Planning care considering individuality due to Hansen’s disease sequelae; b) improving ophthalmological treatment skills, because survivors think that sight is most important after survival; c) preventing external wounds and burn wounds, because survivors cannot feel pain due to perceptual dysfunction; d) learning how to bandage and dress the tip of the hand or foot, and protect it from becoming injured, while also protecting against peripheral circulatory failure; e) eliciting how to deduce load in the same place, depending on survivors’ activities of daily life; and f) becoming the substitute for survivors’ lost eyes, hands, and legs, and supporting their daily life safely and comfortably.

3.2.2 Ability to see through infection and focus on what is hidden

This category shows that nurses knew about the characteristics, progress, and treatment of wounds caused by Hansen’s disease.

It contained three subcategories: g) there are particular infection symptoms of Hansen’s disease, h) having superior judgement for seeing through abnormality of injury, i) knowledge of treatments to protect against advancement in severity from small wounds to amputation.

3.2.3 Ability to acquire survivors’ reliance through the development of skills suited to survivors’ criteria for acceptance

This category shows that nurses set a high value on making relationships with survivors.

It contained five subcategories: j) relationships of mutual trust with survivors are most important because survivors are not replaced; k) if we can acquire skills to meet corrective criterion made by survivors, we can create relationships of mutual trust between survivors; l) if we confront survivors and pay careful attention to the selective criterion made by survivors, we can create relationships of mutual trust; m) I studied about the history of Hansen's disease, in order to understand survivors' experience, n) sustaining a friendly and kind attitude, when facing anger and refusal from survivors who cannot accept new nurses.

3.2.4 Ability to care for survivors’ during death and dying in place of their family whom they had lost due to past compulsory isolation

This category shows that because of knowing their life history, nurses were determined to create a family-like relationship, and care for them in dying and death in place of their family.

It contained three categories: o) becoming a good listener for survivors who had been socially isolated, and becoming a psychological anchor in place of their family; p) supporting survivors to strive toward thinking that “my life has been worthwhile,” q) shouldering the roles of caring for survivors during dying and death is the responsibility of only our nurses in the sanatorium.

3.2.5 Ability to pass down survivors’ suffering to future generation in place of survivors

This category shows that nurses decided to shoulder the role of handing down information from generation to generation.

It contained two subcategories: r) understanding survivors’ despair and wish for suicide, due to abandonment from general society and not living the life they hoped, s) older nurses who know the sanatorium’s history have the mission of handing down the history of Hansen’s disease instead of aging survivors.

4. Discussion

Clinical nursing competency was shown in five categories. In this section, we describe the meaning of each category, and discuss the originality and universality of Hansen’s disease care, and limitations of the study.

4.1 Category Meanings

4.1.1 "Ability to reduce multiple severe sequelae that are characteristics of Hansen’s disease and deuteropathy”

The optimum temperature of Mycobacterium leprae is 30–33 degrees Celsius, which is lower than body temperature, so it causes skin and peripheral nerve lesions at the tip of the body. Hansen’s disease patients have repeated wounds. In addition, the medical reasons for repeated wounds [2] are: 1) patients cannot feel burns and external wounds because of anesthesia, so wounds become severe; 2) losing the foot bottom arch (collapsed arch) causes load at the same place, and soft tissues are crushed and malum perforans pedis occurs at the skin adjoined to the bone; 3) the barrier function of the skin is decreased and skin fissures occur due to skin drying; 4) treatment is delayed by decreasing vasomotor reflex by the dysfunctional autonomic nerve, and if severe infection is added, phegmon and osteomyelitis occur, sometimes requiring amputation; and 5) before the development of promin, the only medicine was hydnocarpus seed oil, so they could not suppress the state of Hansen’s disease.

In addition to the above, because almost all Japanese patients developed the disease by 1955, repeated wounds were affected by socioeconomic factors, such as poor medical systems and hygiene, lack of infrastructure at the sanatorium, and superstition. In addition, having to work in poverty created a negative spiral for worsening wounds, and patients easily selected amputation, because wounds could then be quickly recovered from instead of taking a long time [15]. In this process, multiple severe sequelae occurred, and survivors’ activities of daily life and quality of life continued to decrease.

In addition, survivors think that the eyes are most important. If patients lost eyesight, they could not work and lost income, so they became the poorest in the sanatorium. Thus, they were afraid of lost eyesight [15].

Now, survivors have many wounds, but severe infection needing amputation is rare. One of the reasons for this improvement is nursing practice. For example, nurses have learned how to bandage to avoid collapsing legs, protect artificial legs, shave the callositas to prevent malum perforans pedis callositas, debridement of ulcerated wounds, etc. [16].

Clinical nursing competency for Hansen’s disease nursing is care involving pathophysiology, socioeconomic factors, influence on activities of daily life by continuing sequelae, deuteropathy, patients’ difficulty with lost eyesight, and limb deficiencies.

4.1.2 "Ability to see through infection and focus on what is hidden”

We explained that the characteristics of Hansen’s disease occurred in repeated wounds. In addition, there are three characteristics of the disease to consider.

The first is advancing severity, for example, small wounds cause osteomyelitis and necrosteosis. When lacking appropriate medicine, the only available treatment of osteomyelitis and necrosteosis has been cutting away necrotic tissue from non-necrotic regions to prevent infection from spreading. In Japan, before World War II, amputation, tracheotomy, and ophthalmectomy increased. After the war, they decreased, and plastic surgery against lip dropping and deformation, rhinoplasty, and eyebrow hair transplantation increased [17].

The second characteristic is the refractory nature of the disease. Hansen’s disease patients expressed it as that which “non-aggressive treatment cannot cure”’ [15]. Doctors not understanding Hansen’s disease employed light treatment, for example, not conducting fenestration. However, patients knew that such light treatment could not control severe infection. In previous times, patients used tweezers sterilized by candles, opened the wound, and picked up the pus and necrotized tissues and bone by themselves.

The third characteristic is that discovering the wounds and assessing the severity of the infection from the skin surface is very difficult. Hansen’s disease patients expressed it as “my body collapsed from inside” [15]. The skin surface looked normal, but infection was proceeding under the skin, and disintegration occurred over time. Therefore, we must discover infection early and conduct debridement.

Critical nursing competency for Hansen’s disease nursing involves knowing the characteristics: advancement in severity, refractory nature, difficulty in early discovery and assessing severity, and the ability to assess correctly. This contributes to preventing the occurrence of sequelae and deuteropathy, and decreasing survivors’ quality of life. In addition, one of the reasons for discrimination is the negative changes in appearance of the patient. Nurses’ proper assessment enables appropriate and rapid treatment, and brings recovery without negative changes to the appearance of the patient.

4.1.3 "Ability to acquire survivors’ reliance through the development of skills suited to survivors’ criteria for acceptance”

In Japan, almost all Hansen’s disease patients occurred before World War II. In those days, the global standard for suppressing Hansen’s disease was isolation. In addition, Japan experienced a crisis because of World War II; as Hansen’s disease patients could not become soldiers, they were regarded as a national disgrace. Enforced isolation spread from vagabond patients to patients at home. This treatment instilled fear in people about Hansen’s disease. After World War II, temporarily going outside of the sanatorium was allowed, but the law sustaining isolation continued until 1996.

Almost all survivors entered during childhood and youth, so the average years of living at the sanatorium were about sixty. They lived out their life in the sanatorium. The subjects’ average years worked at the sanatorium was 26.3 years, which was a long time, but shorter than the survivors’ time spent there.

Next, in the sanatorium in Japan before World War II, there was a chronic shortage of medical staff, medication, food, and other items, so patients were living in poverty. Patients worked at all jobs, which included nursing for severe patients, cremation, and funerals, and land reclamation in order to get food. Survivors continue to have pride that they built a mature community and coped with poverty during helplessness [18]. Therefore, they dislike relying on nurses.

In addition, many survivors cannot forgive the inhumane treatment by the sanatorium and government during the same periods, for example, enforced isolation, enforced labor, and vasectomies. Therefore, they had distrust for staff.

Nurses were devoted to creating relationships with survivors, because survivors did not change. If a nurse could not create a good relationship with survivors, she could not work at the sanatorium.

Acquiring skills for treating Hansen’s disease, which included Category 1 and 2, promoted trust and created relationships.

Clinical nursing competency for Hansen’s disease nursing involves obtaining the survivors’ trust by acquiring skills and creating relationships with them. Creating nurse-patient relationships is common, but it is very difficult for Hansen’s disease, and if nurses cannot cope, they cannot work with this group.

4.1.4 "Ability to care for survivors’ during death and dying in place of their family whom they had lost due to past compulsory isolation”

Hansen’s disease is subject to stigma and patients have been discriminated against for a long time. It has been common worldwide, and now patients in developing countries continue to be discriminated against. In Japan, it was the same until around World War II, when patients who could not live became vagrants and went on pilgrimages. In particular, people had feelings of fear about Hansen’s disease because the nation created a law regarding isolation, and patients were searched and entered leprosariums forcibly, and could not escape from there. Patients voluntarily broke off or were forced to break off relationships with family to escape discrimination toward the family.

On the other hand, the overwhelming strategies for Hansen’s disease were isolation and vasectomies. However, patients who could not have children or grandchildren now do not have help in old age.

Now, the role of nurses in the sanatorium is to provide care during dying and death, because survivors are aging (with an average age of more than eighty years). The principle of end of life care is support of dignity of living and dying, and it is the same as in another field. However, sanatorium nurses try to create deep relationships with survivors, which exceed ordinary nurse-patient relationships, and provide care during dying and death as part of these deep relationships. Nurses try to compensate for survivors’ deficiencies, such as not having family due to past policy.

Thus, clinical nursing competencies of Hansen’s disease nursing involve the ethical practice of compensating for past false policy and ensuring the dignity of survivors’ in life and death.

4.1.5. "Ability to pass down survivors’ suffering to future generations in place of survivors”

With respect to the history previously described, survivors have feelings of sadness and anger about three things: 1) their right to live freely was taken away due to forced isolation, 2) they lost relationships with their family due to isolation and discrimination, and 3) they received inhumane treatment in the sanatorium.

In addition, they are afraid of being forgotten in terms of their sadness and anger, and Hansen’s disease history, because they are aging and they will likely die during the next decade. They hope to entrust nurses with the role of continuing to share their experiences, and nurses understand this hope and try to meet the request.

Clinical nursing competency of Hansen’s disease involves understanding survivors’ experiences based on Hansen’s disease history, and taking over the history and continuing to share their experience, namely, becoming the successor of Hansen’s disease history.

4.2 Originality and universality of clinical nursing competency of Hansen’s disease nursing

As discussed previously, Matsutani [10] identified clinical nursing competency in terms of three constructs and seven dimensions. In this section, we discuss the originality and universality of clinical nursing competencies of Hansen’s disease nursing, based on Matsutani’s concepts.

4.2.1 The Ability to apply knowledge and develop interpersonal relationships

All five of our categories related to Matsutani’s concept. By comparing our categories and Matsutani’s concept, three characteristics of Hansen’s disease care are clarified.

First, “applying knowledge,” is the knowledge of history as a requirement (our Categories 3, 4, and 5). To understand survivors’ experiences, nurses must know about the extensive history of Hansen’s disease, policy, medicine, struggles by patients, etc. While a nurse from another field might understand the patient from a holistic viewpoint (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual), if the nurse does not know the history of Hansen’s disease, she cannot understand the whole situation.

Second, developing “interpersonal relationships,” which means creating deep relationships with survivors, is based on all nurses’ job practices (our Category 3). In Japan, the average number of days spent in a general hospital is 17.5 days (2012, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) . In general hospitals, nurses must understand patients based on holistic methods within a short period. However, the characteristics of Hansen’s disease are such that deep relationships are needed, but creating relationships with survivors is very difficult.

Third, in terms of “applying knowledge,” expert nurses possess the ability to assess what general medical staff cannot see (our Category 2), which corresponds to assessment ability for Hansen’s disease nursing. Nurses are well aware of the characteristics of wounds of Hansen’s disease, and preventing them from becoming worse and leading to amputation contributes not only to survivors’ activities of daily living, but also to preventing iscrimination.

4.2.2 Providing nursing care, ethical practice, and professional relationships and management

Our five categories related to Matsutani’s concept, and three characteristics of Hansen’s disease care were clarified.

First, with respect to “providing nursing care,” care of Hansen’s disease involves planning care based on the multiple and severe sequelae of Hansen’s disease, prevention of deuteropathy, and support for activities of daily life (our Categories 1 and 2). Understanding survivors’ experiences and relieving suffering are based on history (our Categories 3, 4, and 5). Care during dying and death and passing survivors’ stories down from generation to generation are new occurrences due to survivors’ aging (our Categories 4 and 5).

Second, with respect to “ethical practice,” nurses try to care for survivors’ during the dying process, in place of their family (our Category 4), because they could not have children and lost family relationships due to past incorrect policy. This is an ethical practice, because losing family is an ethical problem, and nurses try to supplement survivors’ loss created by past policy.

Third, with respect to “professional relationships and management,” not all of our categories correspond, as nurses only set a high value on relationships with survivors.

4.2.3 Professional development and ensuring quality nursing care

Our five categories do not relate to Matsutani’s concept, and one characteristic of Hansen’s disease care is clarified.

First, with respect to “ensuring quality nursing care,” subjects in our study did not have concerns about ensuring quality nursing care, and evaluation criteria were only survivors’ evaluations, for example, whether a nurse was well received by survivors (our Category 3). In addition, nurses rely only on their empirical knowledge, and do not use evidence and explicit knowledge.

In Japan, many medical staff are not concerned about Hansen’s survivor treatment and care. Moreover, the sanatorium is closed from society, for not only survivors but also medical staff and researchers. Because Hansen’s disease has abated, we now treat sequelae and deuteropathy, but do not treat Mycobacterium leprae. In addition, with respect to past incorrect policy, isolation has been discontinued according to the law and the government has apologized to the survivors and offered compensation for damages.

To solve this issue, there is a need for leadership of the nursing administrator at the sanatorium. For example, through contact with this study, the research process heightened nurses’ self-esteem, so that they noticed the importance and value of their role.

5. Limitations of this study

The limitations of this study were that clinical nursing competency was influenced by Japanese history and internal conditions regarding Hansen’s disease, so generalization is difficult.

6. Conclusion

Clinical nursing competency of caring for Hansen’s disease survivors at the final career stage of nurses’ development in Japan was clarified in five categories; 1) Ability to reduce multiple severe sequelae that are characteristics of Hansen’s disease and deuteropathy that results, 2) ability to see through infection and focus on what is hidden, 3) ability to acquire survivors’ reliance through the development of skills suited to survivors’ criteria for acceptance, 4) ability to care for survivors’ during death and dying in place of their family whom they had lost due to past compulsory isolation, 5) ability to pass down survivors’ sufferings to future generations in place of survivors.

The ability to prevent sequelae and deuteropathy is specific to Hansen’s disease. When practicing, nurses need knowledge of history and to create deep relationships with survivors because of past policy. Care for the dying and passing down information are new responsibilities due to survivors’ aging.

We believe that this contribution is theoretically and practically relevant because it informs the treatment of these survivors as well as patients with the disease in developing countries.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

All the authors substantially contributed to the study conception and design as well as the acquisition and interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript.