1. Introduction

Official development assistance is defined as flows to countries and territories on the Development Assistance Committee list of official development assistance (ODA) recipients and to multilateral institutions. South Korea established the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) in 1991 as a grant-special organization. By joining the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development-Development Assistance Committee (OECDDAC) in 2010, it became a fully responsible donor country In spite of its commitment to ODA, since joining; South Korea has ranked the lowest among DAC members in terms of donations. The standard contribution for DAC members is 0.7% of GNI towards ODA expenses [1,2]. However, only five nations (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) have fulfilled the recommendation thus far. South Korea is still below the DAC average of 0.31%; thus, the Korean government plans to reach the goal of 0.25% by rapidly increasing the level of ODA until 2015 or later. One fifth of the ODA expenses are spent in the healthcare sector [3].

Most of the ODA in healthcare has focused on Asian countries, especially in Vietnam, over the past 20 years. The Vietnamese government has accomplished most of its Millennium Development Goals except for those related to HIV/AIDS prevalence [4], and their disease patterns are similar to those of developed countries. Hospital nursing in Vietnam, empowerment of nurses to improve patient safety, and quality of nursing related to nursing-management issues are regarded as less important than clinical-nursing skills. For example, while it is easy to assess various nursing programs in terms of educational duration, the non-establishment of a nurse-license system in Vietnam indicates a lack of focus on the former issues. In provincial regions, the difference in nurses’ educational level among nurses in the same hospital is large compared to that for urban hospital nurses. More than 85% of the nurses in rural settings have only completed two years of college [5].

In addition, there is inequality in terms of access to health services and quality nursing care because of a nursing shortage and the level disparity between urban and rural medical institutions. Furthermore, nursing practices are not differentiated to satisfy patient’s needs, and this provokes potential problems of quality control and nursingservice outcomes [6,7]. Therefore, focused and comprehensive capacity-development programs should be planned to improve community participation and respect ownership of the partner [1,8-10].

Although various staff development programs especially nurses in developing countries have been implemented over the past years. Capacity building which is a term mentions to any interventions applied to produce improved health practices, and several capacity building approaches and measurement were proposed. Capacity building focused on change staffs’ knowledge and attitude by training them is called a bottom-up approach [11,12]. There are many approaches to produce sustainable improvement; the most widely applied methods are training of trainers and dissemination education. Training of trainer is a way to select and train educational program instructors usually nurse managers or nurse educators in subject hospitals, and use them as instructors for their nursing staff development in further training program in dissemination education. For staff development in developing countries, a form of dissemination education which is a training program for each subject institution’s general staffs using those trained instructors with support of outside experts. Trained instructor staffs from training of trainer, dissemination education program for general staffs are considered effective approach overcoming various factors such as language, culture, and health practices.

However, evaluating outcomes are really hard to attain, because knowledge, skills change would not happen right after training program and also it would not guarantee sustainable improvement in developing countries’ staff development. Because it is difficult to explain those changes were attributed to project interventions itself [12,13].

On the other hand, there is a need for long-term endeavors in order to encourage successful capacity building effects [14,15]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify the effects of two training program as capacity building of staff nurses in Vietnam.

2. Materials & Method

2.1 Design

This was a pre-post test design without control group to evaluate the change in knowledge and attitudes of those participants at training of trainer program for nurse managers and dissemination education program for staff nurses.

2.2 Setting and samples

The participants were 31 nurse managers and 320 general nurses working at six hospitals in the central region of Vietnam. Only nurse managers participated in the training of trainer program, and all of the general staff nurses took part in dissemination education. Data from 31 nurse-managers were collected on February 24 and 28, and 299 staff nurses were collected on the second week of March and the last week of May in 2014.

2.3 Development of two categories of core-nursing skills

Throughout the needs assessment implemented in four months prior to this capacity building program, two categories of core skills were identified for the contents of training programs. Each category is composed of twenty-five trauma and maternal-child nursing skills with rationale were developed through expert discussion and review. Especially, those experts were chosen from Vietnamese doctors and nurses who were familiar with nursing skills, and they advised each nursing skills whether it can legally practice within the scope of nursing practice in Vietnam.

All of the 50 core-skills manuals and audio-visual materials (i.e. DVDs) had been previously developed for teaching nursing and paramedic students in Korea. Two Vietnamese doctors, who received the Dr. LEE Jong-Wook fellowship in Korea, had reviewed both the core-skills manuals and DVDs. For the translation phase, three review steps were conducted. First, a translation draft was completed in Korea. A second review was conducted by two Vietnamese nursing faculty members, and a final review was conducted by nurse directors in the provincial health department in Vietnam.

2.4 Implementation of training program

Because the education level of the nurses in the central regional hospitals was lower than that of the nurses in university hospitals in the city, we adjusted the teaching method and utilized audio-visual materials to improve the participants’ understanding of each skill and to overcome language barriers. Bottom-up approach was applied to build capacity of staff nurses in hospital of Vietnam using their managers as instructors.

Finally, a week-long training of trainer program and dissemination education program for staff nurses were implemented two hours per each week for 13 weeks.

2.5 Evaluation of program effects

Pre- and post-training surveys on changes in the nurses’ knowledge, and attitude were assessed. The survey tool was developed by the project team by expert review for content validity. The project team tried to analyze participant's attitude after each training program in terms of perception of present quality of nursing care in general, satisfaction of it, and need of improvement to themselves and peer nurses.

Those independent variables as program effect were mostly used in previous capacity building project in developing countries, like Lee’s [16] Ethiopia maternal health and family planning project and the final report of its associated project [13]. The data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science) WIN 20.0 program. The differences between pre- and post-education responses were analyzed using chi-square tests and paired t-tests.

3. Results

3.1 Participants’ demographic characteristics

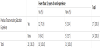

A total of 31 nurse-managers in training of trainer program and 299 staff nurses (93.4%) among 320 in dissemination education replied respectively. And the participants’ descriptive statistics for training of trainer program are presented in Table 1. Of the participants 11 were male (35.5%) and 20 were female (64.5%). Twenty-seven of the participants were in their thirties and forties (87.1%). Twenty-six nurses had a bachelor’s degree, and one nurse had master’s degree in nursing. Twenty-four (77.4%) were nurse-managers.

Demographic statistics for the participants in the dissemination education program are presented in Table 2. Of the participants, 54 were male (18.1%) and 243 were female (81.3%). One hundred eightythree participants were in their twenties. Most of the participants were staff nurses (75.9%), and a majority had received two or fewer years of training in nursing programs (78.9%).

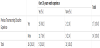

3.2 Need for capacity building training

There was a difference in perception regarding the need for capacitybuilding education according to the duration of the nurses’ work experience (Tables 3 and Table 4). The training of trainer program participants who had worked for more than 10 years felt there was a greater need (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.636) than those with fewer than 10 years of working experience (Pearson’s chi-square test, p = 0.709). The results were similar for the DE participants. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

Note: Pearson’s chi-square test, p = 0.709.

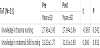

3.3 Changes in knowledge after two programs

Tables 5a and table 5b show the analysis of changes in knowledge between pre-and post training of two of two programs in different areas of nursing-core skills. The average scores on pre- and posttraining changed 27.48 to 27.94 in trauma nursing and 11.77 to 12.81 in maternal-child nursing in training of trainer program; however there was no significant difference statistically. However, those scores were decreased after dissemination education from 27.83 to 27.06 in trauma nursing, and increased 29.07 to 29.19 in maternal-child nursing, and it was also no significant difference statistically.

3.4 Changes in attitudes after two programs

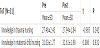

To evaluate attitude change as paired t-test, only 69 participants who were in continuously attended in dissemination education were analyzed, and response to each question was analyzed using paired t-test. There was a distinct change in attitude after two programs was significant difference statistically (Table 6a and Table 6b). This analysis revealed that attitude changes were premise as a way of judgement objectively on themselves and their peers.

After training of trainer program, the attitude on providing quality maternal-child nursing care by themselves positively increased from 1.27 to 1.54, and it was statistically significant (t=-2.015, p=0.056). In terms of attitude change to peers, they do not agree their peers performing quality nursing care in trauma (t=1.803, p=0.083) and maternal child (t=-2.273, p=0.032) area, and it was statistically significant (Table 7a & Table 7b).

Whereas, attitude change in judging their peers negatively decreased after dissemination education program from 1.27 to 1.07, and it was statistically significant (t=3.193, p=0.002).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that attitude change after the training program was related to an improvement in nurses’ critical thinking with respect to their weak points. This could be an effect of reflection writing, because the nurses had to write about what they learned and what they thought daily during the training of trainer program. This stimulated them to contemplate their nursing practices and motivated them to change their way of thinking.

These results are consistent with the findings of former studies [17-21,22]. The literature on training and education programs for healthcare personnel in developing countries shows a significant change in knowledge and skills, and so the positive outcome observed in this study in those areas could be anticipated. However, the literature does rarely anticipate the attitude change in the nurses’ evaluation of themselves and their peers that was observed in the current study. One explanation may be that repetitive, condensed core-nursingskills training motivates nurses to think of building capacity as a team and empowers them to grow professionally.

A majority of the participants indicated that they had sufficient knowledge with skills as a group as well as individually in the pretraining survey. However, in the post-training survey, there was a change in the nurses’ perception of their peer’s level of nursing care. They indicated that their peers’ nursing quality was not good after two program, and it was not analyzed in previous other research findings [13].

5. Conclusion

The goal of this study was to identify the change in knowledge, skills, and attitude in Vietnamese nurses after training of trainer and dissemination education programs. The important changes were in attitude and an improvement in knowledge and skills. These results indicate that nurses have the potential for development in areas to guarantee patient safety and quality nursing services.

Based on the current results, the Korean government should focus on evaluation of participants’ attitude change in critical thinking in order to monitor and compare various capacity-training projects across countries. Furthermore, leadership trainings for Vietnamese nurse-managers are indispensable for empowering general nurses in developing their professional nursing practice so as to increase patient-care outcomes and the quality of service. This will also contribute to sustainable development.

Finally, implementing these training programs in developing countries is recommended for the reciprocal accountability agenda [22].

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Kang, SJ substantially contributed to the study conception and design as well as the acquisition and interpretation of the data. Chang, KJ contributed to the study design and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Lee, MK approved the final version of the manuscript for publication and supervised the research group.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank everyone who helped me complete this dissertation. Without their continued efforts and support, I would have not been able to bring my work to a successful completion.

I would especially like to thank Korea Foundation for International Healthcare for supporting this project and Ms. Tu Nguyen for her assistance in communicating with the study participants.

Funding Disclosure

The authors have no funding to disclose.