1. Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative disorder produced by clonal proliferation of multipotential hematopoietic cells. It is a biphasic disease that presents a chronic early phase characterized by a massive expansion of myeloid precursor cells and mature cells that prematurely escape from the bone marrow but maintain their ability to differentiate normally. This phase is followed by an acute phase in the form of blast crisis, which can have a fatal outcome [1].

CML is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome, due to a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 that forms a fusion gene of Breakpoint cluster region (BCR)/Abelson murine leukemia gene (ABL)[2].

At present, there are 5 drugs for CML that act by inhibiting tyrosine kinases (TK) including, the ABL kinase, which is involved in the genesis of this disease.

The first drug was imatinib, after which nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, and ponatinib were developed. These drugs have different chemical structures and a different pharmacological profile.

This article aims to review the pharmacological characteristics of each of these drugs so that, as an expression of their strengths and weaknesses, conclusions can be drawn for clinical practice.

2. Chemical Structure

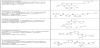

Table 1 describes the chemical structures of the 5 molecules. Bosutinib is a quinazoline [3,4], the other 4 drugs share a central pyrimidine-like structure [5-9]. Three of the drugs, imatinib, nilotinib, and posatinib are benzamides.

These chemical differences can partly explain the selectivity of the pharmacological effect, the different involvement in pharmacological interactions by alteration of Cytochrome P450 (CYP), and the activity of some transporter proteins. Furthermore, some of the adverse effects shared by nilotinib and ponatinib may have their origin in the presence of a trifluorophenyl in the structure of both these compounds.

3. Pharmacodynamics

The most important event in CML is a reciprocal chromosomal translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) that occurs in stem cells. It is a translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22 known as the Philadelphia chromosome and is present in up to 90% of patients with CML. The molecular consequence is the presence of a BCR/ABL chimeric gene on chromosome 22 and its reciprocal ABL/BCR on chromosome 9. The latter, unlike the first, does not have transcriptional activity and does not seem to have functional activity in CML development. In contrast, the BCR/ABL fusion gene is a constitutively activated TK capable of activating various transcriptional processes [10] and is found exclusively in the cytoplasm of cells forming complexes with cellular cytoskeleton proteins [11].

Increased BCR/ABL TK activity phosphorylates diverse cellular substrates that alter the process of cell differentiation and proliferation. Activated substrates include various transcription activation signals: RAS/MAPK, PI-3 kinase (PI-3K), CBL and CRKL, and the JAK-STAT and SRC pathways [12-14].

Once activated, the ABL kinases regulate signaling involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton vital in cell protrusion, cell migration, morphogenesis, adhesion, endocytosis and phagocytosis, as well as the regulation of cell survival and proliferation pathways [15-17]. This aberrant signaling activity can give rise to various types of tumors, including CML.

With this background it is not surprising that identifying drugs that are able to inhibit ABL kinases is a priority to control tumor evolution, including CML.

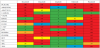

The 5 available drugs inhibit various TKs, including BCR/ABL, but with different inhibitory profiles, which can potentially explain differences in efficacy and toxicity [18]. Table 2 summarizes the in vitro activity of the different BCR/ABL TK inhibitors (TKIs), obtained in a comparative study [19].

Table 2 shows that bosutinib is the only drug that does not inhibit C-KIT and that has a lower inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFRα). These characteristics are important since the first is the membrane receptor of stem cell factor (SCF), also termed" steel factor" or "c-kit ligand", a polypeptide that activates the precursors of bone marrow blood cells and is also present in other cells.

C-KIT mutations in the interstitial cells of Cajal in the digestive tract can be key in the development of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). The C-KIT receptor is related to macrophage colony- stimulating factor (CSF-1) and to PDGF, hence inhibiting C-KIT generates myelosuppression as an adverse event. C-KIT inhibition can also lead to cutaneous adverse events because C-KIT stimulates the proliferation and migration of melanoblasts and germ cells. On the other hand PDGF has an important role in embryogenic development, cell proliferation and migration and angiogenesis.

It is also noteworthy that ponatinib is active against BCR/ABL strains that are resistant to other drugs; however, it also inhibits kinases that may be related to adverse cardiac and vascular effects.

The activity of BCR/ABL inhibitors depends on the presence of resistance mutations. It is estimated that 20-30% of patients either do not respond to initial treatment (primary resistance) or relapse after the initial response [20,21]. Resistance to imatinib and to other BCR/ABL inhibitors can also occur because of infra therapeutic drug concentrations, due to lack of compliance by the patient, inadequate doses, alterations in the activity of the isoenzymes that metabolize the inhibitors, or alterations of the transporter proteins that are involved in the pharmacokinetic process [22-25]. There are some BCR/ABL mutations that are partially or completely resistant to BCR/ABL inhibition. For example, the BCR/ABL T315I mutation is resistant to all BCR/ABL inhibitors except ponatinib [9,26,27].

4. Pharmacokinetics

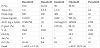

From the pharmacokinetic point of view, TKIs are characterized, as noted in Table 3, by oral absorption, a wide distribution within the total volume of body water, and the elimination through CYP450 metabolism.

4.1 Absorption

The absolute bioavailability of these drugs ranges from 14% for dasatinib to 98% for imatinib. In general, absorption is slow with the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) occurring between 0.5 and 6 h [28-35].

There is proportionality between the Cmax and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) with the dose administered for bosutinib, dasatinib, nilotinib and ponatinib. However, with dasatinib, the values of Cmax and AUC are higher when administered once a day compared with twice daily [36]; contrary to what happens with nilotinib [34,37].

At steady state, imatinib AUC increases 1.6-fold compared with the AUC of the first dose [38,39]. Similarly, there is an increase in Cmax at steady state for bosutinib (2-fold), nilotinib (3.8-fold), and ponatinib (1.5-fold) [32,34,40].

4.1.1 Effect of food on absorption

While the administration of bosutinib at a dose of 200 mg and 400 mg to healthy volunteers together with food, increased Cmax and AUC values by 2-fold and 1.4-fold compared with fasting administration; no differences were found in the case of dasatinib, imatinib [41] or ponatinib [42]. The incidence and severity of the adverse events with bosutinib 400 mg in fasting conditions were similar to bosutinib 600 mg administered with food, suggesting that administration with food improves tolerability [28].

Administration with a high-fat meal increases nilotinib Cmax and AUC by 112% and 82%, respectively. When nilotinib intake occurred 30 minutes or 2 hours after the meal, the increase in bioavailability was 29% and 15%, respectively [43]. Therefore it is recommended to not eat any food in the 2 hours before and in the hour after taking nilotinib, so that the bioavailability increase does not lead to increased adverse events.

4.2 Distribution

In plasma, drugs in this class are found mostly protein bound to albumin and alpha-glycoprotein; in the case of nilotinib and imatinib especially to the latter. In animal models, it has been shown that high concentrations of α1 glycoprotein may be associated with an absence of response to imatinib. The administration of intravenous clindamycin, a drug that is fixed in high proportion to α1 glycoprotein, can reduce the bioavailability of imatinib up to 2.9-fold [44,45].

The volume of distribution of these drugs exceeds the body water content [31,34,35,46,47].

Dasatinib is able to slightly cross the blood-brain barrier with a plasma concentration of 0.05-0.28 ng/ml [48]. Imatinib diffuses marginally to CSF; however, the CSF levels are up to 74-fold lower than in plasma. This reduced diffusion is probably related to the fact that these drugs are a P-glycoprotein substrate, which limits diffusion to the nervous system [34,49,50].

4.3 Elimination

All drugs in this class are metabolized before elimination. As described in Table 4, several isoenzymes of CYP450 are involved in their metabolism, with potential drug-drug interactions. Bosutinib, dasatinib, imatinib and their respective metabolites are eliminated primarily in the faeces, while urinary excretion does not exceed 5% [31,35,39,51-54].

Bosutinib has the longest elimination half-life, with mean values ranging between 32.4 and 41.2 h, while dasatinib has the shortest halflife (5.6 h) [31,32,52]. The other drugs have comparable half-lives, between 17-22 h.

4.4 Pharmacokinetics in special situations

4.4.1 Hepatic impairment

The Cmax and the AUC of bosutinib increased 2.42-fold and 2.25- fold in patients with Child Pugh cirrhosis A, 1.99-fold and 2-fold in patients with Child Pugh B, and 1.52-fold and 1.91-fold in patients with Child Pugh C. The elimination half-life was 86, 113 and 111 h in each of the grades [55]. A dose adjustment is recommended in patients with hepatic impairment since there is a potential risk of QTc prolongation. This adverse event has not been described in patients who did not have liver function abnormalities [56].

Patients with abnormal liver function may have a 50% increase in the AUC of imatinib [57] as well as is probably the case for ponatinib [35].

In general, caution is recommended when using any of these drugs in patients with hepatic insufficiency.

4.4.2 Renal impairment

In patients with several renal impairment, the AUC and Cmax of bosutinib increased by 60% and 34%, respectively; and in patients with moderate renal impairment, the increase is 35% and 28%, respectively. The dose should be adjusted if creatinine clearance is below 50 ml/min [58]. In the case of dasatinib, Cmax and AUC are reduced in patients with moderate or severe renal insufficiency. Caution and close monitoring of patients with renal impairment is recommended [31].

The AUC0-24 of imatinib at steady state increases 2.1-fold in patients with moderate renal impairment [59,60].

In the absence of data on administering ponatinib to patients with renal impairment, it is advisable to also use caution in patients with moderate and severe renal insufficiency [35].

4.4.3 Pediatrics

In children, the Cmax values of imatinib at 260 mg/m2 and 340 mg/m2 were 3.6 mg/l and 2.5 mg/L, respectively, with a Tmax of around 3.5 h. When treating children with CML, the recommended dose of imatinib is 260-300 mg/m2/day [61].

5. Interactions

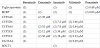

The 5 drugs are metabolized, to a greater or lesser extent, through isoenzymes of CYP450 (Table 4). In addition, these drugs are substrates and at times, inhibitors of the activity of transport proteins such as P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein BCRP. Table 5 summarizes the inhibitory activity of these drugs and Table 6 details the various types of interactions.

5.1 Effect of BCR/ABL inhibitors on CYP450 and transport proteins

5.1.1 Bosutinib

Bosutinib is a CYP3A4 substrate, but is not a substrate for any of the remaining Cytochrome P450 (CYP). Furthermore, it does it seem to have the capacity to induce or inhibit these isoenzymes.

5.1.2 Dasatinib

Dasatinib is metabolized through the CYP3A4 isoenzyme. In vitro, it is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and BCRP but it does inhibit these transporters. Dasatinib is also a substrate of the human organic cation transporter type 1 (hOCT1), although with a lower affinity than imatinib [62,63]. Dasatinib has inhibitory activity against CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP2C9 and CYP2A6.

5.1.3 Imatinib

Imatinib is mainly metabolised by CYP3A4, whereas CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A5 play a smaller role. With long-term administration, imatinib tends to inhibit its own metabolism, and CYP2C8 becomes more relevant for its metabolism [64]. Imatinib is also a substrate of hOCT1, P-glycoprotein, and BCRP, and can inhibit the activity of these two last ones. It can also competitively inhibit the metabolism of drugs that are substrates of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.

5.1.4 Nilotinib

Nilotinib is metabolized through CYP3A4, and is a substrate of P-glycoproteinand BCRP. In addition, it inhibits CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, UGT1A1, P-glycoprotein and BCRP, the latter in an important way [65]. In vitro, nilotinib has been shown to induce CYP2B6.

5.1.5 Ponatinib

Ponatinib is a CYP3A4/5 substrate and in smaller amounts is also a substrate of CYP2C8 and CYP2D6. Ponatinib is not a substrate, but it inhibits the activity of P-glycoprotein and BCRP, with reduced IC50 values. Therefore, ponatinib has the potential to increase the plasma concentrations of drugs that are substrates of these transporter proteins such as: digoxin, pravastatin, dabigatran, methotrexate, or sulfasalazine [66-74].

5.2 CYP450 interactions

As indicated, all BCR/ABL inhibitors are substrates of Cytochrome P450 (CYP); therefore, their rate of elimination can be altered by other drugs that increase or reduce the activity of these isoenzymes. In addition, dasatinib, imatinib, nilotinib, and ponatinib regulate CYP450 interaction since they can reduce the enzymatic activity of some of the isoenzymes. This characteristic is not shared by bosutinib, and is a better choice for the polymedicated patient, thereby avoiding potential drug-drug interactions.

5.2.1 Drugs that alter the metabolism of BCR/ABL inhibitors

The activity of isoenzymes can be increased (induced), except that of CYP2D6, or reduced (inhibited). With inhibition, there is a reduction in the rate of elimination of the drugs that are metabolized by the isoenzyme. Consequently, the drugs are accumulated in the body leading to an increased risk of toxicity that remains as long as the dose of the drug is not reduced. With induction, there is a reduction of the pharmacological activity of the drug because the drugs are eliminated too quickly from the body.

5.2.2 Bosutinib and dasatinib

As a CYP3A4 substrate, bosutinib experiences an increase in Cmax and AUC when combined with inhibitors of this isoenzyme, such as ketoconazole [29,75] or aprepitant [76]. On the other hand, when combining bosutinib with rifampicin, an enzyme inducer, there is a reduction in bosutinib bioavailability [30]. Similarly, concomitant administration of dasatinib and ketoconazole increased the AUC of dasatinib [77], whereas rifampicin reduced it.

5.2.3 Imatinib

All drugs that inhibit CYP3A activity may increase the bioavailability of imatinib, such as ketoconazole, levothyroxine, voriconazole or amiodarone. The same is not true for ritonavir; although it is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 activity, there is a compensatory mechanism of induction [78-83]. CYP3A inducers or P-glycoprotein, such as rifampin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin and St. John's Wort, can reduce the exposure of imatinib, potentially compromising its therapeutic activity. The administration of a single dose of rifampicin to 10 healthy volunteers reduced AUC of imatinib by 68%, along with a 24% increase in the AUC of the active metabolite [84]. Similar results were described with St. John’s Wort [85-89].

5.2.4 Nilotinib

The bioavailability of nilotinib increases when it is used in association with CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole, which increase 3-fold the AUC of nilotinib [43]. Nilotinib intake with fruit juice can increase AUC by up to 60%. Conversely, administration of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampicin, reduces AUC 4.8-fold [90].

5.2.5 Ponatinib

With ponatinib, a dose reduction to 30 mg once a day is recommended when administered concomitantly with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors. When combining with ketoconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, there was an increase in ponatinib’s AUC0-∞, AUC0 to last quantifiable value, and Cmax of 78%, 70%, and 47%, respectively [91]. CYP3A4 inducers can lead to a reduction in systemic exposure of ponatinib, so associated use with carbamazepine, phenobarbital or rifampicin should be avoided.

5.3 Drugs whose metabolism is altered by BCR/ABL inhibitors

5.3.1 Bosutinib

As noted, bosutinib does not alter the activity of Cytocrome P450 (CYP); however, the remaining 4 BCR/ABL TKIs do.

5.3.2 Dasatinib

Dasatinib behaves as an inhibitor of CYP450 activity so it reduces the clearance of drugs that are eliminated through this isoenzyme. This inhibitory effect may be time dependent [85]. A single dose of 100 mg of dasatinib increased the AUC and Cmax of simvastatin, a known CYP3A4 substrate, by 20% and 37%, respectively. Therefore, CYP3A4 substrates with narrow therapeutic margins (eg, astemizole, terfenadine, cisapride, pimozide, quinidine, bepridil or ergot alkaloids [ergotamine, dihydroergotamine]) should be administered with caution in patients receiving dasatinib. There is also a potential risk of CYP2C8 inhibition, which may lead to increased concentrations of substrates of this isoenzyme such as glitazones.

5.3.3 Imatinib

Imatinib increases the intestinal absorption of cyclosporine through inhibition of P glycoprotein and the cytochrome CYP3A4, and may increase toxicity [92,93]. Co-administration of imatinib with metoprolol increased the bioavailability of metoprolol by 23% [94]. Compared with simvastatin alone, co-administration with imatinib had a 3-fold increase in the AUC of simvastatin and was associated with a 70% reduction in the clearance of simvastatin [95]. Relevant interactions have been described with other CYP3A4 substrates, such as verapamil and diltiazem, with increases in plasma concentration increase when co-administered with imatinib. Clinically relevant interactions with simvastatin, amiodarone and quinidine have been described and may also have clinical implications. Therefore, it is recommended to avoid these medications and look for safer alternatives when using imatinib [95].

Imatinib inhibits the glucuronidation of paracetamol, leading to hepatotoxicity and liver failure; so reduced doses of paracetamol are recommended when taking imatinib. As CYP2C9 substrates, acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon, have shown increased concentrations when co-administered with imatinib [96-98].

Co-adminsitration of imatinib and levothyroxine requires an increase in the dose of levothyroxine, up to 2-fold, probably due to the induction of uridine diphosphate glucuronyl transferase (UGT) activity [79,80].

Caution should be exercised when administering imatinib with other drugs that are substrates for cytochrome CYP3A, CYP2C9(warfarin), CYP2D6 (antidepressants, antipsychotics), P-glycoprotein (digoxin or dabigatran), and BCRP (mitoxantrone, topotecan and methotrexate).

5.3.4 Interactions with transport proteins

All BCR/ABL inhibitors, except bosutinib, are substrates of transport proteins such as P-glycoprotein, BCRP, or hOCT1. These proteins have the function of expelling the drug from inside the cells to prevent absorption, reduce distribution, or facilitate elimination. Therefore, concomitant administration with inhibitors or inducers of these proteins has consequences that are similar to inhibiting the isoenzymes that metabolize them: bioavailability increase or reduction.

5.3.5 Bosutinib

It has been suggested that bosutinib may be an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein, but clinical studies with dabigatran, a specific substrate of P-glycoprotein, have not shown any change in pharmacokinetics [99], allowing us to rule out the involvement of transport proteins in relevant interactions with bosutinib.

5.3.7 Dasatinib

Drugs that inhibit the activity of BCRP or CYP3A4, such as verapamil, erythromycin, clarithromycin, cyclosporine, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and posaconazole, increase the bioavailability of dasatinib, with an increase in intracellular concentration. In turn, dasatinib can slightly inhibit transport proteins and moderately inhibit the activity of CYP3A4, changing the exposure of some drugs. Specifically, co-administration with dasatinib increases the bioavailability of simvastatin [83], and is not recommended with CYP3A4 substrates such as verapamil or diltiazem.

5.3.8 Imatinib

The administration of imatinib with a mixed inhibitor of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein increased plasma concentrations and also intracellular concentrations of imatinib. There is a potential risk when co-administering imatinib with verapamil, erythromycin, clarithromycin, cyclosporine, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, or posaconazole [92,100]. Similarly, some P-glycoprotein transport inhibitors, such as intraconazole or cyclosporine, can reduce biliary excretion or modify the passage of the drug into the blood-brain barrier. The inhibition of P-glycoprotein by proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as pantoprazole, increases intracerebral imatinib penetration. Interactions with quinidine, ranitidine or midazolam, known inhibitors of hOCT1, can paradoxically increase plasma concentration and reduce intracellular concentration [69].

5.3.9 Ponatinib

Ponatinib is not a substrate, but it inhibits the activity of P-glycoprotein and BCRP, with reduced IC50 values. Coadministration of ponatinib can increase the plasma concentrations of drugs that are substrates of these transporter proteins such as: digoxin, pravastatin, dabigatran, methotrexate, or sulfasalazine.

5.3.10 Other interactions

The absorption of bosutinib is dose and pH-dependent. The solubility of bosutinib, like that of the other BCR/ABL TKIs, is reduced with increased gastric pH. Use of PPIs should be avoided so that the bioavailability of bosutinib is not reduced [101,102]. If pH reduction is required, H2 antacids or histamine antagonists should be used, to be taken about 2 hoursbefore or after the TKI is administered [56,103]. This interaction has also been described when dasatinib is administered with famotidine and omeprazole [104].

The use of antacids instead of H2-antagonists or PPIs should be evaluated in patients receiving treatment with bosutinib or dasatinib. The absorption of ponatinib is very dependent on solubility that is pH-dependent, so caution is recommended when using drugs that increase gastric pH.

Using imatinib with magnesium and aluminum salts is not associated with significant alterations in drug absorption [41,105].

In some clinical trials, QT prolongation was reported with dasatinib. Cardiac arrhythmias with death have been described, probably related to abnormalities of ventricular repolarization. Coadministration with drugs that produce the same effect as digoxin, quinolones, methadone or various antipsychotics may increase the risk, for which a close electrocardiographic control of the patients is recommended [106,107]. Nilotinib has also been associated with QT prolongation and with cases of sudden death, so it should not be administered to patients who are receiving drugs that produce similar symptoms, alterations in congenital QT syndrome, hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia [106,107].

6. Monitoring plasma levels

6.1 PK/PD

The relationship between pharmacokinetics and efficacy or tolerability is of great clinical interest.

6.2 Bosutinib

In a population analysis conducted with bosutinib, a relationship between the bioavailability of the drug and the incidence of diarrhea was reported, after adjusting to a maximum effect model, Emax. The probability of developing diarrhea and rash was higher among patients with higher AUC values. There was no evidence of possible relationships between exposure to the drug and the incidence of other adverse events. No relationship was found between bosutinib AUC and major cytogenetic response (MCyR) at 24 weeks [108,109].

6.3 Dasatinib

A greater and faster response was achieved with dasatinib at a dose of 100 mg than with 400 mg of imatinib once a day; however, pleural effusion was reported as an adverse event in 19% of the patients treated with dasatinib and it required treatment discontinuation in 29% of patients [110]. The efficacy of dasatinib is related to its mean concentration at steady state with optimal values of 14.16 ng/ml with 100 mg once a day and 14.32 ng/ml with 50 mg twice a day [36]. Both pleural effusion and cytogenetic response are significantly related to the plasma concentration of dasatinib, with a 1.22-fold increased risk of effusion per each 1 ng/ml increase in minimum plasma concentration (Cmin) of dasatinib [36]. Throughout the phase I and phase II studies, pleural effusion has been reported less frequently when dasatinib is administered once a day versus administration twice a day [111,112].

It has been pointed out that the Cmin of dasatinib must not exceed 2.5 ng/ml because the incidence of pleural effusion is significantly increased at higher levels. Therefore, the administration of 100 mg once daily appears to be the most reasonable dose to achieve efficacy, while reducing the incidence of adverse events [112,113].

C2 (plasma concentration at 2 hours), Cmax and AUC of dasatinib are significantly lower in patients who have a T315I mutation in BCR/ABL than in those without the mutation. Therefore, in addition to adjusting Cmin, an adjustment to C2 or Cmax is recommended, aiming that these values are at 50 ng/ml to avoid increasing the risk of developing mutations in the BCR-ABL due to low exposure to dasatinib [114]. In addition, because dasatinib Cmax values correlate with complete cytogenetic response (CCyR), some authors recommend dosing the drug to reach a Cmax or C2 of approximately 50 ng/ml and a Cmin below 2.5 ng/ml [115].

6.4 Imatinib

Imatinib has a high interpatient variability with coefficient of variation for AUC that ranges between 39% and 51%, with doses of 400 and 600 mg, respectively. There is no relationship between drug exposure, body weight, and body surface. The influence of the CYP3A polymorphism does not justify the interpatient variability, which seems to be associated with P-glycoprotein polymorphism [38]. Cmin at steady state, after administration of 400 mg a day, ranges between 100 ng/ml and 5000 ng/ml. In a Japanese population, interpatient variability has been described with a coefficient of variation between 32.8% and 62.9% [116-118]. There is also a remarkable intraindividual variability, with coefficients of variation for Cmin between 8.4% and 49.3% [119].

Several studies have indicated that patients who achieve imatinib concentrations below 1000 ng/ml have a significantly worse response when compared with those who achieve higher concentrations [120-133]. Therefore, it is currently accepted that pre-dose concentration (Cmin) with imatinib should reach at least 1000 ng/ml [119,134]. Both median overall survival and progression-free survival have been associated with higher doses of imatinib. In fact, the cumulative incidence of CCyR or major molecular response (MMR) during the first 18 months of treatment was significantly lower in patients treated with 200 mg daily, compared with those who received 300 mg or 400 mg. Therefore, in patients treated with doses of 300-400 mg who develop intolerance, the reduction of the dose to <200 mg should be avoided and treatment with other TKIs is recommended [118].

BCRP, is encoded by the ABCG2 gene (BCRP) and its fundamental function is to act as an efflux transport protein, primarily expressed in the small intestine and in the bile canaliculus [135,136]. In these locations, it is involved in the absorption, distribution and elimination of a large number of clinically relevant drugs, including imatinib. The presence of a polymorphism that affects a single nucleotide, mainly 421C/A, significantly reduces the function of this transporter protein. The need to adjust the dose in relation to the concentration achieved was significantly lower in Japanese patients who presented genotype ABCG2 421C/C than in patients with other genotypes C/A or A/A [137]. It has also been described that the clearance of imatinib in patients with a 421C/A genotype is significantly lower than that of patients with a 421C/C genotype, therefore they have higher Cmin concentrations than those with a 421C/C genotype [138,139].

BCRP also contributes to the extracellular excretion of imatinib. Therefore, the presence of polymorphic genotypes can also affect the elimination of the drug. It has been described that 54% of the patients who achieved complete molecular response (CMR) had the 421C/A allele, while 67% of the patients who did not reach CMR had the genotype 421C/C [140]. Several studies have shown an increased MMR in patients with genotype ABCG2 421C/A [139,141,142].

Imatinib, at the recommended dose of 400 mg a day, often has serious adverse events such as neutropenia, edema or skin rash, which result in poor compliance by the patient, the need to stop treatment early, and even therapeutic failure [143]. In fact, doses higher than 400 mg a day have been associated with an increased incidence of adverse events and with the need to discontinue treament with imatinib. A Cmin greater than 3180 ng/ml has been associated with a high frequency of Grade 3/4 adverse events such as neutropenia [124]. Elevated Cmin has also been associated with cutaneous rash and edema [120,124]. In fact, imatinib Cmin greater than 3000 ng/ml should be avoided.

6.5 Nilotinib

Nilotinib also has great intraindividual variability, with coefficients of variation greater than 36.4%, hence the importance of performing periodic Cmin tests [119]. Fasting administration of nilotinib at a dose of 150 mg twice a day or 200 mg twice a day leads to a faster and more important response than that of imatinib 400 mg once a day [144]. CYP3A4, 2C8, 2C9, 2D6, and UGT1A, among others, intervene in the elimination of nilotinib [65]. UGT1A is responsible for the glucuronide conjugation of bilirubin, and upon competing for the enzyme, nilotinib leads to hyperbilirubinemia [145]. High exposure to nilotinib is associated with an increased incidence of hyperbilirubinemia [146,147]. The presence of UGT1A1 polymorphisms is associated with especially high levels of bilirubin, specifically the genotype UGT1A1*28/*28 [148]. In clinical studies, the nilotinib-mediated inhibitory effect of UGT1A1 is important in patients who previously had a reduced metabolizing status for genotypes *6/*6, *6/*28, and *28/*28 [149]. In addition, in these patients, hyperbilirubinemia occurred within the first 3 weeks of treatment with nilotinib. Patients who present this risk of developing hyperbilirubinemia, should be treated with an initial dose of nilotinib of 150-200 mg twice a day, and it may even be preferable to choose another TKI due to the high risk for hyperbilirubinemia [150].

Although no significant correlation was found between the Cmin values of nilotinib at 12 months and MMR response [148], patients with nilotinib levels greater than 500 ng/ml required a significantly shorter time to reach the CCyR or MMR response [151].

The current recommendation for the optimal Cmin of nilotinib at steady state is 800 ng/ml after an initial administration of 600 mg a day [115]. At this concentration, patients with slow metabolization of UGT1A1 had a 50% incidence of Grade 3/4 hyperbilirubinemia. Therefore, for these patients the optimal concentration should be 500 ng/ml, although this can be associated with inefficiency.

6.6 Ponatinib

There is little information regarding ponatinib; although, in a phase I study a dependence of the response was observed, with the dose administered to patients with acute Ph+ lymphoblastic leukemia. Dose-dependent activity has also been described in a study performed in 43 Ph+ patients in whom a ≥50% reduction of CRKL phosphorylation, a surrogate for BCR-ABL inhibition, was observed in 67% and 94% of patients receiving doses of 8 and 15 mg respectively [40].

In a clinical trial, MCyR response at 15 months was significantly higher among patients who were between 18 and 44 years of age, or 45 and 64 years old, compared with those who were older than 65 years, with p<0.001 [152]. A relationship has been described between the incidence of adverse events and high doses of ponatinib, advanced age, duration of the disease, previous history of diabetes or ischemia, the baseline presence of neutrophilia, and high platelet numbers [153].

Table 7 summarizes the available data on monitoring plasma levels. The determination of concentrations should be performed at least at 3, 6 and 12 months.

7. Tolerability

Establishing differences among the 5 drugs in the incidence and severity of adverse events is complicated. For example, nilotinib has a very low incidence of fluid retention, and probably has less haematological toxicity than the other TKIs; although it seems that the incidence of rash, headache, pancreatitis and cardiovascular effects is higher than that observed with imatinib. Dasatinib, on the other hand, less peripheral edema, but gastrointestinal toxicity and pleural effusion are more frequent than with imatinib. Bosutinib is characterized mainly by diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain; however, there is less intensity of edema and muscle, and bone pain. Finally, ponatinib, when compared with imatinib, has a profile of important cardiovascular toxicity. In addition, it leads to higher incidence of rash, abdominal pain, headache, and pancreatitis, and lower nausea, muscle pain and diarrhea, than imatinib. In any case, the incidence of adverse events reported in clinical studies is relevant since more than 95% of patients reported some type of adverse event and about half of them needed a temporary discontinuation of the treatment or reduction of the dose. Many of these adverse events are related to hematological alterations that are resolved quickly.

Most of the adverse events occur during the first 3 months of treatment and can be handled easily, by reducing the dose or by interrupting the medication before Grade 3 or 4 toxicity appear. Surprisingly, despite the high incidence of adverse events and their apparent seriousness, there are few patients who need to permanently discontinue treatment for this reason (9-19%) [110,154,155].

Cardiovascular adverse events have been reported with imatinib. In a retrospective of 1276 patients, it was reported that 22 patients (1.7%) had heart failure, 11 of whom continued treatment after dose adjustment and heart failure management. Other TKIs have a lower cardiac toxicity profile, with cardiac events ranging from less than 1 to 4% of patients treated with dasatinib or ponatinib; while they have not been described with dasatinib or with bosutinib [156-160].

QT prolongation has been described with all TKIs, although the highest frequency has been reported with nilotinib. During the clinical development phase of nilotinib, a few cases of sudden death were reported. To evaluate potential risks, it is recommended to have an electrocardiogram (ECG) before treatment initiation, at 1 week after starting treatment, and when clinically indicated [34,37,161].

It has been suggested that treatment with nilotinib and dasatinib, compared with imatinib, carries an increased risk of arterial and venous events, as well as acute myocardial infarction [162]. It has also been described that nilotinib causes elevated blood glucose levels, hyperlipidemia, increased body mass index (BMI), as risk factors relevant to cardiovascular toxicity; although no thromboembolism events have been reported [163,164]. However, there is a higher indicence of peripheral arterial occlusive disease with nilotinib compared with imatinib, but not when compared with other controls that are not TKIs [165]. In a 6-year follow-up study, 10% of patients treated with nilotinib 300 mg twice daily were reported to have cardiovascular events, including 4% of patients with peripheral arterial occlusive events. In comparison, overall cardiovascular events were reported in 3% of patients in the control arm of imatinib [160]. Higher doses of nilotinib, 400 mg twice a day, which are approved for use in refractory or relapsed patients, report cardiovascular events in close to 16% of patients [160].

In a 5-year follow-up study of dasatinib, the incidence of ischemic alterations was 5% in the dasatinib arm compared with 2% in the imatinib arm [159]. In the case of bosutinib, the incidence of vascular arterial toxicity appears to be similar to that of imatinib [154]. However, ponatinib is associated with severe cardiovascular toxicity: 8% arterial thrombosis, 5% acute myocardial infarction, 2% peripheral arterial occlusive disease, and 2% cerebrovascular events [158]. With this drug, incidences of serious arterial thrombotic events have been reported in 5-7% of patients [152,166], and some type of cardiac or vascular toxicity has been described in 49% of patients [167]. These findings occurred in the first clinical trials with ponatinib; this drug was withdrawn from commercialization in 2013 to continue the evaluation of toxicity. Cardiovascular toxicity related to TKIs has been described by several authors [168,169].

Pulmonary complications have been reported with imatinib and nilotinib, including interstitial lung disease (ILD) in less than 1% of patients [170-173]. All TKIs can have pericardial or pleural effusions as adverse events; however, dasatinib seems to stand out, with onestudy reporting an incidence of pleural effusion during the first year of 10%, which increased to 29% by the end of the study. Overall, 20% of patients required discontinuation of dasatinib treatment due to this adverse event [159]. The frequency of pleural effusion appears to be higher with bosutinib than with imatinib. Three out of 250 patients treated with bosutinib discontinued treatment as a result of a pleural effusion, compared with none of the patients receiving imatinib [154]. Pulmonary arterial hypertension related to the use of dasatinib has been described in up to 5% of patients, some of which required discontinuation of treatment [159], although it is clinically reversible [173].

All TKIs have reported gastrointestinal adverse events, especially during the first 6 months of treatment. Imatinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib have similar rates of nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain; but, bosutinib has the highest incidence of diarrhea [154,174]. Dasatinib has reported the highest incidence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, which has been attributed to alterations in platelet function and thrombocytopenia [175-177].

Elevation of pancreatic enzymes has been described, with nilotinib and ponatinib having the highest incidence. In the case of ponatinib, this adverse event is dose limiting in up to 7% of patients treated with the drug [152].

Elevation of liver enzymes has been reported with all TKIs, although the highest incidence occurs with nilotinib, bosutinib and ponatinib [178,179].

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Pfizer.