1. Introduction

The global number of children weighing less than 2,500 g at birth is 15 million, accounting for 15-20% of all births [1]. The preterm birth rate has continuously increased over the past 20 years, and it remains increasing. In Japan, the rates of newborns weighing less than 2,500 g at birth in 2015 were almost double those in 1980(male: 4.8 to 8.4%, female: 5.6 to 10.6%) [2]. All over the world, especially in developing countries, more and more extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants are surviving due to recent advances in perinatal care including surfactant replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation [3]. The mortality rate among ELBW infants has also markedly decreased since the late 1970s in Japan. The neonatal mortality rate among ELBW infants weighing more than 1,000 g at birth decreased from 20.7% in 1980 to 3.8% in 2000. Similarly, among those weighing more than 500 g at birth, it decreased from 55.3 to 15.2%, respectively [4,5]. However, survival without sequelae is not achieved in all preterm (lowbirth- weight, LBW) infants, and many of them need continuation of medical care after coming through critical conditions [6].

LBW infants have a large number of health risks, including: retarded growth [7,8], a poor developmental prognosis [9-11], cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and severe motor and intellectual disabilities (SMID) requiring medical care [12]. Furthermore, many of their mothers develop a sense of guilt about having delivered an LBW infant, face mental health problems due to mother-infant separation [13-15], and experience anxiety over the growth and development their children. Such anxiety is observed in 75% of all parents of ELBW infants, and it increases during the children’s stays at NICUs (Neonatal Intensive Care Units) and soon after discharge from these units [16]. Intensifying their anxiety over home care, families of ELBW infants markedly need extensive information and support after NICU discharge [17,18]. As a challenge to be urgently addressed, the National Perinatal Association (NAP) [19] recommends that psychosocial support for parents of children admitted to NICUs be further promoted toward the provision of comprehensive family support [20].

A large number of LBW infants, who have been saved and cared for in NICUs, return home with conditions still requiring medical care. In Japan, the number of children aged 0-19 requiring medical care was 17,000 in 2015, revealing a 1.8-fold increase within10 years [21]. Among children receiving home care, approximately 3,000 use artificial respirators, and about 1,000 of them are age 0-4, accounting for the majority. These values have increased 12- and 4.5-fold, respectively, within10 years. Nearly 150 children a year are discharged from NICUs while using artificial respirators [22], and 67% of them finally return home. In the case of medical care-dependent children with SMID, their mothers as their main caregivers at home bear a heavy burden, but available social resources remain insufficient, resulting in poor social support for these mothers. Therefore, 70% of all medical care-dependent children with SMID receive long-term home care [12]. The rates of using home-visit nursing facilities and home care support services among them are limited to 18 and 12%, respectively. Home care for pediatric patients lacks common frameworks that connect medical and welfare services, and consequently poor multiprofessional collaboration forces their mothers to act as a key person who connects multiple facilities.

Maternity record handbooks are a basis for Japan’s maternal and child health measures. The major significance of these handbooks is allowing the management of information regarding maternal and child health from pregnancy to delivery and infancy in a single handbook [23]. To date, more than 30 countries have adopted similar handbooks to improve maternal and child health, and create systems to continuously provide related services [24-28]. However, as the growth curves and parenting information presented in these maternity record handbooks are based on the growth of full-term infants, they are often inappropriate for the growth assessment or parenting of LBW infants. In addition, they have no spaces to describe the child’s postpartum condition in the NICU. In this respect, the use of maternity record handbooks does not ensure sufficient support for LBW infants and their families.

To address such a situation, a group of mothers, who had delivered ELBW infants, developed a parenting record handbook called the “Little Baby Handbook (LBH)”, with the aim of providing parenting support for mothers of LBW infants [29]. The LBH is currently used by the families of children admitted to the NICUs of 3medical institutions in a prefecture.

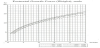

The LBH contains information regarding the growth, development, and parenting of LBW infants, administrative bodies promoting maternal and child health, and various types of subsidy, as well as messages (with empathy and encouragement) for mothers and other family members (Table 1). It also shows a growth curve for each weight category to assess the growth of ELBW infants [30] (Figure 1). The process of development from “becoming able to hold up his/her head” to “walking 2 to 3 steps” is classified into 9 milestones on a list. For each developmental milestone, it is possible to enter the corrected age in months, age in months after birth, and the day when the child achieved that milestone (Table 2). There are also spaces to record the child’s postpartum condition in the NICU and on discharge from it (Table 3). Explanations of administrative bodies promoting maternal and child health and each type of subsidy, with relevant contact addresses (names and telephone numbers of facilities/departments in charge) may be regarded as a source of support that encourages mothers to adopt actions, and empowers their parenting. The lower section of each page presents messages from peers (other mothers/ families of LBW infants) to share their experiences related to the growth, development, and parenting of their LBW infants from birth to the school period. The extensive and informative contents of the LBH to support mothers (families) of LBW infants may enable them to develop perspectives on the growth and parenting of their LBW infants, with a sense of security and hope, and consequently reduce their anxiety over their current situation. In this respect, the LBH may play an important role in the field of home care support for LBW infants, where public service systems have yet to be established.

To the author’s knowledge, there have been no surveys examining the usefulness of the LBH to enhance LBW infants’ and their families’ QOL, or promote system reforms or improve the quality of services for the former. The present study focused on the parenting record handbook (LBH) as a source of support that provides mental health care for and empowers mothers with LBW infants, and examined its benefits through a focus group interview with parents using it.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

A qualitative design with an inductive approach.

2.2 Participants

There were 6 candidates, mothers of ELBW infants weighing less than 1,500 g at birth who were using the LBH at the time of the study. The inclusion criterion was “a mother caring for and parenting an LBW infant at home”. Mothers with mental disorders and those with a marked tendency toward postpartum depression were excluded. The candidates were selected by the representative of the group of parents of LBW infants, who had created the LBH, at the researcher’s request.

2.3 Data collection

As demographic variables, the age, working status, family structure, situation when delivering an LBW infant, and current use of medical/ welfare services were examined using a questionnaire prior to the interview. The focus group interview was conducted using an interview guide to examine participants’ views on the LBH and the contents of an ideal parenting record handbook for LBW infants and their mothers. The session was held in a quiet conference room within a hospital where the parent group held meetings. To maintain their anonymity and sense of security during discussion, participants used cards displaying a nickname instead of their real names during the interview. The interview lasted for 90 minutes, and it was recorded using an IC recorder with the participants’ agreement.

2.4 Data analysis

Important items were extracted from participants’ actual expressions, and their semantic contents were carefully examined for categorization [31]. Participants’ views on the LBH were analyzed, focusing on the benefits and challenges of this handbook and contents of an ideal parenting record handbook for LBW infants and their mothers.

2.5 Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Epidemiological Research Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University (approval number: E-1154). To obtain their consent to participate in the study based on their free judgment, a document outlining the study and the interview guide were sent to the candidates by mail. The explanatory document specified that the cost of respite care to ensure the safety of their children during the focus group interview would be charged to the researcher, and the interview would be immediately discontinued whenever the physical condition of any child worsened. It also explained the study objective, participation based on free will, and participants’ right to withdrawal at any time. Those who consented were provided with an explanation again before the interview to obtain their written consent.

3. Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics

Four mothers and 1 married couple, who had children weighing less than 1,500 gat birth, were included (Table 4). Among the 6 candidate mothers, 6 consented, but 1 of them subsequently cancelled due to physical deconditioning in the sibling of her ELBW infant. One father desiring to participate in the focus group interview was also included, with his written consent, considering that novel findings on the utilization of the LBH and related needs might be obtained from him as a father parenting an LBW infant. All participants were in their thirties, and 5 and 1 were living only with a spouse (nuclear households) and with grandparents, respectively. The age of their children was 3±2.5 years. The children were born with a weight of 800.6±205.8 g at 26.6±2.4 weeks of pregnancy, and they stayed at the NICU for 4.2±2.3 months. Two of them used outpatient services at developmental rehabilitation centers, and 3 were treated with rehabilitation.

3.2 Themes

Five core categories, 27 categories, 53sub-categories, and 167 codes were created. In the following section, they are shown in [], {}, <>, and “ ”, respectively. The core categories are shown in [ ]. The categories are shown in { }. The sub-categories are shown in <>. The codes are shown in “ ”. The words in ( ) were added by the researcher to complement explanation of each situation.

There were 3 core categories, explaining the benefits of the LBH: [mental support obtained from mothers with the same experience], [growth and developmental assessment of the child], and [QOL enhancement through information-based support] (Figure 2). The 2 other core categories [a tool for information-sharing between families and multiple professionals] and [wishes for the utilization of the LBH as an ideal parenting record handbook]outlined the future challenges of the LBH and contents of an ideal record handbook, respectively.

The 5 core categories were reconstructed to develop overall perspectives on the parenting record handbook for mothers of LBW infants as an ideal record handbook in the process from the delivery of an LBW infant and his/her admission to the NICU to daily life after discharge.

3.3 Benefits of the LBH

[Mental support obtained from mothers with the same experience]

The mothers who had delivered an LBW infant regarded their < maternal emotions > and experience of < expressing breast milk in loneliness > after the < delivery of an LBW infant > as {not being understood by others}. Mother-infant separation and the necessity of expressing breast milk alone after the admission of their children to NICUs made them feel lonely. Messages from other mothers with the same experience presented in the LBH provided these mothers with {relief} and {mental support and encouragement}. {Communication with peers (other mothers with the same experience)} through the handbook was a source of continued support for them after the discharge of their children from NICUs.

{Not being understood by others}

< Delivery of an LBW infant >

“As a matter of fact, it is difficult for other people to understand this. They may hardly imagine the birth of a very small baby.” (A)

< Maternal emotions >

“I try to explain my situation, but they just say, ‘That’s tough’ or something. I am even badly hurt by some of their statements.”

{Relief}

< Feeling relieved >

“I felt relieved to read the preface on the back page of the cover and learn that LBW infants can also grow big.” (B)

[Growth and developmental assessment of the child]

The mothers favorably evaluated the LBH, as it allows {recording according to the child’s growth and development} - < recording according to the child’s development >, < developmental recording based on the corrected age in months and age in months after birth>, and < entry of the day when the child achieved each milestone as a developmental step>. They added data to the list of developmental milestones and growth curves for ELBW infants, and confirmed the growth process of their children, consequently {being pleased by the child’s growth and development}. Furthermore, the messages from other mothers of children born at similar weeks of pregnancy also helped them develop {perspectives on the child’s growth}. They described the LBH as a {wonderful tool to record parenting} and {genuine maternity record handbook}.

The mothers regarded the LBH as < affirming LBW infants as children > and< the appropriate maternity record handbook for us >. They also considered it not only as an instrument to record < the child’s growth steps>, but also < a material to reflect on the child’s birth with him in the future >.

{Recording according to the child’s growth and development}

< Developmental recording based on the corrected age in months and age in months after birth >

“Recording based on the corrected age in months is very helpful.” (B)

“I appreciate this handbook, because it allows recording according to my child’s growth. For example, I can enter the day when he achieved each milestone.” (A)

{Mother-child bond strengthened by the LBH}

< A strengthened bond with the child >

“I feel that the bond between me with my child has been strengthened. This (LBH) connects us.” (C)

[QOL enhancement through information-based support]

The contents of the LBH guided the mothers toward the {acquisition of expertise} and {utilization of public subsidies and the list of available consultation services}. They were also beneficial in terms of the {promotion of peer support}. These effects consequently enhanced the mothers’ and their children’s QOL. The acquisition of expertise provided the former with a basis for< understanding the risk of complications >, and deepened their< understanding of development >. Additionally, the presentation of public subsidies and a list of available consultation services encouraged the mothers to apply for health insurance subsidies, and use institutions providing consultation services. < The parent group’s address connecting mothers with the same experience > also promoted peer support for families with LBW infants.

{Acquisition of expertise}

< Understanding the risk of complications >

“(I had been told about my child’s condition through my husband before, but) with the handbook, I could learn about his risks and developmental prognosis in detail by myself.” (B)

{Benefits of public subsidies and the list of available consultation services}

< Using these resources to apply for health insurance subsidies >

“These resources have been helpful to apply for health insurance subsidies to support premature babies (and their parenting).” (B)

{Promotion of peer support}

< The parent group’s address connecting mothers with the same experience >

“Without this handbook, I might not have visited here(the parent group). It was because I happened to find this address for inquiries and applications on the last page…” (F)

3.4 Future challenges of the LBH

[A tool for information-sharing between families and multiple professionals]

The mothers of LBW infants commonly faced {difficulty in accurately recognizing the child’s postpartum condition in the NICU}. Therefore, they expressed their {wishes for the description of postpartum findings in the LBH by medical institutions}. They also expected the LBH to function as {a tool for information-sharing between families and multiple professionals}, < wishing it would become possible for families and multiple professionals to freely describe the status of outpatient and welfare service use in the LBH to share such information >.

The mothers wished that postpartum findings would be described in the LBH by medical institutions, as they had had difficulty in explaining their children’s postpartum conditions when visiting other medical institutions for consultation after discharge from the initial perinatal care centers. They thought that accurate information based on postpartum findings described in the LBH by medical institutions would be helpful for them to explain their children’s postpartum conditions and situations when using other medical constitutions or welfare services.

{Difficulty in accurately recognizing the child’s postpartum condition in the NICU}

< Difficulty in explaining the child’s postpartum condition >

“During the initial consultation, the doctor asked me, ‘Do you understand the name of the diagnosis, Mother?’ But the name was too long and difficult to understand…” (A)

{Wishes for the description of postpartum findings in the LBH by medical institutions}

< Wishing postpartum findings described in the LBH >

“It would be helpful if there is also a page to chronologically describe the child’s condition at each period after birth, including the name of each diagnosis, period of each onset, and day of each surgery.” (F)

{Information-sharing by sharing the LBH between the family and multiple professionals}

< Wishing it would become possible for families and multiple professionals to freely describe the status of outpatient and welfare service use in the LBH to share such information >

“A page or space to share information regarding speech or occupational therapywith therapists would be helpful…” (A)

[Wishes for the utilization of the LBH as an ideal parenting record handbook]

The mothers looked for the {dissemination of the LBH} as an ideal record handbook that allows {recording according to the condition of each LBW infant}, and, therefore, they wished it would become {publicly usable}. Considering the merits of< using both a maternity record handbook and LBH >, < integrating a maternity record handbook and LBH into a single book>, and < using only the LBH after delivery>, they expected the LBH to allow recording according to the condition of each LBW infant.

At present, the LBH is < not usable for medical institutions>, as it is not officially approved. Therefore, the mothers were< wishing the LBH was publicly usable>. One of them also expressed her dissatisfaction with conventional maternity record handbooks and the need for a publicly usable handbook that promotes the recognition of her child, stating: “When the LBH becomes publicly usable, I may feel that my child is also recognized…”.

The mothers also wished that the LBH would be disseminated as a source of support for other mothers of LBW infants with similar experiences.

{Publicly usable}

< Wishing the LBH was publicly usable >

“If the LBH becomes publicly usable, doctors and therapists will also be able to describe their findings in it. That may be the best way.” (E)

{Dissemination of the LBH}

< Wishing the LBH was disseminated >

“When I posted a photo of the LBH on Instagram, I received inquiries from mothers of babies admitted to NICUs throughout Japan, asking where they could get the handbook.”(C)

< Support for mothers without peers >

“A considerable number of mothers are struggling alone, as it is difficult to find peers in the NICU.” (D)

4. Discussion

In this section, the core categories are reconstructed to discuss the benefits and future challenges of the LBH and contents of an ideal parenting record handbook based on the mothers’ wishes in the process from the delivery of an LBW infant and his/her admission to the NICU to daily life after discharge.

When supporting mothers who have delivered LBW infants, it is important to continuously provide support for both the mothers and children based on mental support for the former.

The mothers involved in the present study regarded their < maternal emotions > after the < delivery of an LBW infant > as {not being understood by others}. They described the necessity of expressing breast milk alone after mother-infant separation as < expressing breast milk in loneliness >. As a tendency of such mothers, they look for psychological care provided by medical professionals, and their mental status becomes particularly unstable immediately after delivery, developing a sense of guilt about having delivered an LBW infant and mental health problems due to mother-infant separation. They also face difficulty in expressing their uncertainty as a parent and negative emotions toward their children to medical staff who are directly providing care for the children [32]. In fact, with regard to < expressing breast milk in loneliness >, one of the mothers stated: “I felt I was expected to do my best for breastfeeding. When I expressed my breast milk, I couldn't help crying”, suggesting that she had not been able to freely express her true emotions to medical staff.

In such a situation, the LBH was a source of {mental support and encouragement} for the mothers, as represented by the sub-categories < feeling relieved >, < feeling more peaceful >, and < feeling relaxed >. The preface of the handbook also provided them with {relief}, as they found hope for the growth of their children, reading it. Regarding this, a mother stated: “I felt relieved to read the preface on the back page of the cover and learn that LBW infants can also grow big”. This message explains that even if they were born small, children grow up, overcoming their difficulties on a step-by-step basis, and parent-child bonds are nurtured through parenting. Furthermore, the messages presented in the lower section of each page describe other mothers’ sense of security when their children got out of critical conditions, as well as their affection for the children. The contents of these messages also represented the mothers’ emotions in various settings of parenting, such as: “It was not until he grew big enough to be held in my arms and touched that I could realize that this is my child”, and “It was a great pleasure to see each pipe, tube, or infusion line be removed from my child. I just wanted to have him out of the incubator soon”.

To support maternal mental health, not only mental support from medical professionals, but also peer support is important. Mental support from NICU staff tends to be limited, whereas peer support groups benefits mothers to share their negative emotions and experiences with empathy [33]. The messages from other mothers with the same experience contained in the LBH provided effective mental peer support for the mothers, as recounted by the categories {mental support and encouragement} and {relief}. The majority of mothers who have participated in support programs provided by peer support groups acknowledge the usefulness of these programs [34-36]. Similarly, the LBH may be useful in 2 aspects: functioning as a source of peer support for mothers and facilitating their access to peer support whenever they need it.

The mothers also favorably evaluated the LBH, as it allows {recording according to the child’s growth and development}. While {being pleased by the child’s growth and development} by confirming his/her progress, the mothers also developed {perspectives on the child’s growth}, reading messages from other mothers with the same experience. As LBW infants grow and develop more slowly than fullterm infants, many of their mothers are anxious about their growth, wishing it healthy [37-39]. Therefore, when conducting the growth and developmental assessment of LBW infants, it is important to support their mothers to bring the children up with pleasure to observe their growth and development [40]. The recording of growth and development utilizing the growth curves for ELBW infants (The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare Study Group on Mental and Physical Disabilities) and developmental milestones shown in the LBH reduced the mothers’ anxiety over their children’s growth and development, and aroused their pleasure. In this respect, the LBH may also be helpful for the establishment of favorable motherchild relationships, in addition to the growth and developmental assessment of LBW infants.

Information support through the LBH helped the mothers make financial arrangements for the parenting of their LBW infants and adopt actions to resolve various problems, consequently improving the QOL of their entire families. The contact address of the parent group shown in the LBH also served as a resource for the mothers to seek peers. The provision of knowledge related to child life, public health and medical services, including financial support, and satisfactory consultation functions enhance maternal confidence [41]. However, many families, who care for LBW infants at home after NICU discharge, and consequently go out on limited occasions, face difficulty in accessing parent groups, networks of mothers, and detailed information regarding public health, education, and welfare services [42]. An LBH that facilitates obtaining knowledge of parenting and information regarding social resources may be a beneficial support measure to improve the QOL of LBW infants and their families living in communities.

On the other hand, the mothers of LBW infants found it difficult to explain their children’s postpartum conditions, and wished related findings described in the LBH by medical institutions (doctors in charge and NICU staff). The description of postpartum findings during NICU stays in the LBH by medical institutions may be effective to store accurate information and useful to explain the child’s postpartum condition to other medical institutions for consultation. For these medical institutions, the collection of accurate information through the LBH may be helpful. The mothers also wished it would become possible for families and multiple professionals to freely describe the status of outpatient and welfare service use in the LBH as a tool for information-sharing. As a support handbook to promote collaboration between parents of LBW infants and related institutions, an electronic-version NICU discharge support handbook is currently available [43,44]. This electronic-version handbook and the LBH share some challenges to be useful for information-sharing. The LBH may be useful as a tool to promote family (patient)-centered multiprofessional collaboration and support for children and their families living in communities.

5. Study Limitations

The present study qualitatively examined users of a handbook for mothers of LBW infants admitted to the NICUs of 3 medical institutions in a single municipality. In the future, it may also be necessary to quantitatively examine the study topic, involving an increased number of subjects, in order to provide integrated support for these mothers.

6. Implications for Practice

The LBH may be useful to mentally support mothers of LBW infants, and help them understand and assess the growth and development of their children, and obtain support information. The growth curves for ELBW infants presented in the LBH may facilitate maternal care and guidance for LBH use after discharge, provided by NICU nurses, and collaboration between mothers and public health centers and developmental rehabilitation facilities from NICU admission onward. The public information contained in the LBH may also be useful for facilities used by LBW infants.

7. Conclusions

- The LBH was useful to mentally support mothers of LBW infants, and help them assess the growth of their children. It also functioned as a source of information regarding public health/ medical services and peer support for these mothers.

- The mothers of LBW infants wished the LBH would be a tool for information-sharing between families and multiple professionals, publicly usable, and disseminated.

The results of the present study suggest that the LBH reduces the sense of guilt in mothers of LBW infants, and empowers them toward the development of affirmative parenting emotions and behaviors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Yukiko Tomoyasu and Ikuko Sobue conceptualized and designed the study, and designed the data collection; Yukiko Tomoyasu were responsible for the acquisition of data and the analyses; Ikuko Sobue supervised the data analyses; Yukiko Tomoyasu and Ikuko Sobue completed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the mothers and father who cooperated with the study, and Satomi Kobayashi, the representative of the parent group Poco-a-poco, for her understanding of the study objective and cooperation.