1. Introduction

Research inquiries have provided evidence that spiritual perspectives play a significant role within the context of depression. But fail to provide substantial evidence comparing spiritual perspectives and comfort levels. Spiritual perspective is, “a form of self – transcendence that emphasize religious as well as broader spiritual views and practices such as prayer, meditation, forgiveness, and belief in God or a Higher Purpose where there is a distinct since of consecutiveness to something greater than self ” (as cited in [1], p.9). Research studies provide evidence that engaging in regular prayer, meditation or other spiritually related practices are linked to a thickening of the brain cortex [2]. Investigator(s)’ suggested that these activities can help guard against depression, particularly in those who are genetically predisposed to the mental health disorders. The study involved 103 adults at either high or low risk of depression, based on family history. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings revealed thicker cortices in those participants who placed a high importance on religion or spirituality than those who did not. Moreover, “the thicker cortex was found in the same regions of the brain that had otherwise shown thinning in people at high risk for depression” ([2], para 1-10).

A study examining the spiritual perspectives of 102 pregnant African American women found negative correlations among spiritual perspectives, depression, anxiety, and stress [3]. Spiritually related studies were also conducted on children. An experimental study was conducted on 40 chronically ill hospitalized children in Florida. The children were between 6 and 15 years of age. The 20 children in the experimental group received three Godly Play interventions. Godly play is an intervention designed “for improving physical, emotional, and spiritual responses of chronically ill hospitalized children” ([4], p. 261). The 20 children in the control group received a fairy tale book. The findings suggested that Godly Play had a significant effect on depression, anxiety, and spirituality of children, and the parents of children who participated in Godly Play were more satisfied with hospital care than parents whose children did not engage in Godly Play. “. . . Many pediatric healthcare providers note, this type of intervention is an important component to a child's healing” ([4-6], p.1).

In addition to studying the impact of spirituality and mental problems, such as depression, many studies have examined the impact of spirituality on the health and well-being of African Americans and the importance of implementing spiritual interventions within health care practices [6,7]. Figueroa et al. studied the impact of spirituality on health-care-seeking behaviors and found that spirituality influences health and health-care-seeking behaviors among African Americans [7]. Evidence of cultural differences regarding the importance of spirituality and religion among African-Americans were found within the context of depression and substance abuse [8,9]. Several studies indicated that African Americans placed more importance on spirituality than Caucasians when examining perceived importance of the spiritual aspect of care for mental and physical concerns [8,10].

Despite extensive evidence demonstrating the impact of spirituality on African Americans’ health, research suggest that health care professionals feel uncomfortable incorporating spirituality within therapy [11,12]. A study conducted in 2017 examined spiritual perspectives among nurses found that although many nurses recognized that spirituality has value, nurses often felt uncomfortable assessing their clients’ spiritual domain and incorporating spiritual interventions into their health care practices [11]. The nurses’ discomfort may have developed as a result of the lack of clarity in understanding the differences between spirituality and religiousness, or feelings of being ill-prepared educationally [11,12]. Nonetheless, studies have indicated a need to find ways to apply spirituality as well as set professional standards in the health care of African Americans [13].

Furthermore, there is a gap in the literature on African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual perspectives and comfort levels related to incorporating spirituality within the context of depression. This is a problem since spirituality has been found to be an important component in the mental health and well-being of African Americans [14,15]. If the African American families’ spiritual perspectives or comfort levels were found to be greater than mental health care nurses in the context of depression, a problem may exist of nurses not being able to provide culturally competent interventions. “Culturally competent care for African Americans requires sensitivity to spirituality as a component of the cultural context” ([16], p.57).

The independent variables for this study are spiritual perspectives and comfort levels of African American families and mental health nurses. The dependent variable for this study is within the context of depression, meaning the therapeutic regimen for depression. Therefore, the spiritual activities the participants reported experiencing within the context of depression, depends upon their spiritual perspectives and comfort levels. The purpose of this research study was to explore the spiritual perspectives and comfort levels of African American families and mental health care nurses within the context of depression. This study supported the idea of testing a theoretical framework designed to increase the comfort levels of mental health nurses and other health care providers while attempting to incorporate spiritual interventions within family therapy [17]. Also, this study explored how different levels of spiritual perspectives and spiritual comfort may impact therapy for African American families within the context of depression. Exploring these spiritual perspectives and comfort levels within the context of depression provided pertinent information and contributed to the growth of nursing as an art and a science, given that the results from this study have inspired the initiating and testing of a culturally sensitive treatment option. In addition, this study can present a foundation for planning unique practice measures for families of various cultures and ethnic groups experiencing any type of mental or physical illnesses.

2. Methods

2.1 Research design

This study used a non-experimental mixed-method design guided by the Neuman Systems Model. The Neuman Systems Model views nursing as being primarily concerned with defining appropriate actions in stress-related situations [18] and views the person or client system as a five-layered being consisting of physiological, psychological, socio-cultural, developmental, and spiritual variables. These five variables are usually represented by a concentric circle, consisting of a central core, lines of resistance, normal lines of defense; and flexible lines of defense. The lines of resistance and lines of defense protect the central core” ([19], p. 1). Stressors attack and attempt to penetrate flexible lines of defense. The person or client system encompasses four dimensions–individual, family, community, and a social issue [19]. According to Neuman [as cited in 20], “The family system is exposed to stressors that affect its stability and threaten its state of wellness” (p. 66). In this study, depression is the stressor that is attempting to penetrate the lines of defense for the African American families. Nurses could define appropriate actions by incorporating spirituality as a method of primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive strategies. Figure 1 illustrates the Neuman Systems Model applied to African American families within the context of depression.

2.2 Research questions and hypotheses

The following research questions and hypotheses (H1 and H2) were addressed in this study:

- Is there a significant difference in the spiritual perspectives of African American families and mental health nurses within the context of depression?

- There is a difference in African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual perspectives as measured by the spiritual perspective scale within the context of depression.

- Is there a significant difference in the spiritual comfort levels of African American families and mental health nurses related to incorporating spiritual interventions within the context of depression?

- There is a difference in African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual comfort levels as measured by the spiritual comfort level indicator within the context of depression.

- What are the spiritual perspectives of African American families within the context of depression?

- What are the spiritual perspectives of mental health care nurses within the context of depression?

- What are the comfort levels of African American families related to incorporating spiritual interventions, including beliefs and activities, within the context of depression?

- What are the comfort levels of mental health care nurses related to incorporating spiritual interventions, including beliefs and activities, within the context of depression?

3. Conceptual-Theoretical-Empirical

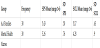

Fawcett expressed that “conceptual models act as guides for generating and testing middle-range theories by focusing on certain concepts, and by applying the model’s research rules” ([21], pp. 9-12). Table 1 presents the conceptual model concepts and the middle-rangetheory concepts for this study. Conceptual-theoretical-empirical (C-T-E) structures were developed for this study to illustrate the linkages among the conceptual model, empirical research methods and middle-range-theories that were tested and generated. They also address specific research questions and hypotheses. Figure 2 presents the C-T-E for the middle-range-theory that was tested. Figure 3 C-T-E illustrates linkages among the conceptual model, empirical research methods, and middle-range-theory that were generated.

The guidelines for research associated with the Neuman Systems Model are congruent with the C-T-E structures in that the phenomenon of spirituality includes basic life processes for African Americans. Nurses can enhance these processes by encouraging patients to use spiritual practices to deal with their illnesses. The phenomena of interest, which are spiritual perspectives and comfort levels, encompass physical, psychological, sociocultural, and spiritual variables; the family system; lines of defense; created environment; the characteristics of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extra-personal stressors; and the elements of primary, secondary, and tertiary preventions [22]. In this study, depression is the stressor that is attempting to penetrate the lines of defense for these families.

4. Participants

The participants for this study consisted of 30 mental health care nurses comprising mostly of two ethnic groups, African Americans (n = 14) and Caucasians (n = 13), with 1 Hispanic nurse and 1 Asian nurse. There were 30 (n = 63) families. Sixty-one of the family participants identified themselves as African Americans, and 2 of the family participants identified themselves as biracial.

The nurses reported caring for individuals and families with members diagnosed with an Axis I of depression. The families consisted of members who self-reported an Axis I diagnosis of clinical depression and no other mental clinical illnesses. The absence of other mental clinical illness was a requirement for this study in order to control for an extraneous variable such as a religious psychosis.

The African American families included individuals who were able to read and write English, and the age range of the families was between 17and 85 years of age. The age range of the nurses was between 29 and 68 years of age. The family structures consisted of couples, singleparent families, and extended family members. The participants were recruited from the Hampton Roads, Virginia area health care facilities, churches, social organizations, and community centers. The number of participants used was determined by the analysis procedure. A full description of the sample is provided in Table 2.

5. Data Collection Procedure and Ethical Considerations

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals were obtained from a historically black university (HBCU) in Hampton Virginia and a behavioral health hospital in Williamsburg Virginia. Permission was also granted by Dr. Betty Neuman to use the Neuman System’s Model and Dr. Pamela Reed to use the Spiritual Perspective Scale in family research. Focus groups were conducted in locations that were accessible and safe for the participants and investigator [23]. Such as hospital conference rooms, community centers’ office spaces, and two of the participants’ homes. Participants were given a packet at the beginning of the focus group meeting that contained an information sheet, letter of appreciation, consent form; demographic form (DF), Spiritual Comfort Level Indicator (SCLI) [24], Spiritual Comfort Level Indicator for Health Care Providers (SCLIHCP) [25] and the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) [26]. The information sheet and the informed consent forms were read to the participants by the researcher. After the consent forms were signed, the participants were asked to complete the rest of the packet, prior to participating in focus group interviews. Therefore, the participants were asked to complete the quantitative portion of the study prior to the qualitative portion in order to decrease any possible influences from focus group responses on instruments scores. This strategy helped deter a great deal of power and influence over members due to group cohesiveness and assisted the researcher in obtaining a level of validity and credibility [27]. All focus group interviews were taped recorded and transcribed verbatim by the researcher. The participants’ names were coded for confidentiality, and all data are maintained in a secured area which is only accessible to the primary investigator. Debriefing consisted of allowing the participants to express how they felt about completing the SPS and the SCLI (for the families) or SCLIHCP (for the nurses) and presenting them with a letter of appreciation and a $10.00 (for families only) gift certificate. Participants were aware that they were able to withdraw from the study at any time if they became upset or uncomfortable in any way.

6. Instrumentation

Instruments include the DF, the SPS, SCLI, SCLIHCP and a twopart semi-structured interview guide. The SPS is a 10-item instrument that measures participants’ perceptions of the extent to which they hold certain spiritual views and engage in spiritually-related interactions.” The SPS is reported to have an internal consistency reliability (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.90) in a general sample of 400 adults who range in age and levels of health [28]. The SPS, as with many other studies, performed well in this study (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.92) suggesting that it is an appropriate tool for measuring African American family members as a group or individually.

Most of the comfort scales found in the literature measured pain; none were found that measured spiritual comfort as it relates to health care. Therefore, the spiritual comfort level indicators, SCLI (clients) and SCLIHCP (health care providers) were developed by the researcher and a statistician for the purpose of exploring the families’ and nurses’ spiritual comfort levels. The SCLI and the SCLIHCP were evaluated by a content expert and revised by the researcher prior to being used in this study. Comfort levels as a plural noun is defined on the spiritual comfort level indicator as the physical or psychological circumstances in which somebody feels most at ease. The SCLI and the SCLIHCP are 10-item scales adapted from the SPS. The SCLI and the SCLIHCP were designed to measure participants’ comfort levels specifically related to the extent to which they will incorporate spirituality or engage in spiritually related interactions within health care. The SCLI and the SCLIHCP measure the same variables from different perspectives, either that of the health care professional or the client. For instance, question 3 on the SCLI that was administered to the families asked, “How comfortable are you about reading spiritually-related material with a doctor or a nurse?” Question 3 on the SCLIHCP that was administered to the nurses asked, “How comfortable are you about reading spiritually related material with your patients?” The value ranges for questions 1-4 on the SCLI and the SCLIHCP range from 1–being not comfortable at all, to 6–being very comfortable. The value ranges for questions 5-10 are from 1-strongly disagree to 5–strongly agree. From this point forward, the term SCLI will be referring to the SCLI and the SCLIHCP.

The SCLI was effective for this study, with a Chronbach’s alpha = 0.88. The construct of comfort appeared to have been operationalized on the scale appropriately for this study. This was evident after analyzing the SCLI scores and the participants’ overall descriptions of comfort as it relates to spirituality within the context of depression.

The semi-structured interview guide contains two parts. Part I of the interview guide was designed for the families to facilitate the creation of overall descriptions of spiritual perspectives, spiritual experiences, beliefs, and activities and determine how comfortable they are in incorporating their spiritual beliefs and activities into therapy within the context of depression. The interview guide also aided in describing experiences of spiritual activity within the context of depression or any other therapy. Part II of the interview guide was designed for the nurses to facilitate the creation of their overall descriptions and experiences of spiritual beliefs and activities, to determine comfort levels with regard to incorporating spiritual interventions within their practice, and to determine how important it is for them to incorporate spiritual interventions into their practice. The interview guide also facilitated their overall descriptions about their experiences of spiritual activity within the context of depression or any other therapy. Content validity of the interview guide was established by expert researchers who have worked with nurses and minority populations [29].

7. Results

7.1 Phase I: Pilot testing

Phase I of this study consisted of pilot testing the SPS on family. Although the SPS was used in many research inquiries, the instrument had not been used on family members holistically; therefore, the purpose of pilot testing the SPS was to evaluate the best method of obtaining a family-based spiritual perspective. Participants completed the SPS individually and with their family members. Although the family group scores were slightly higher, both the individual and family group SPS mean scores were high. The families were also asked to evaluate on a scale of 1-6 their level of agreement, with 1 being the lowest level of family agreement and 6 being the highest level of family agreement for each of the 10 SPS items.

7.2 Presentation of results for phase I: Pilot testing

Five families consisting of 12 African American men (n=3) 25% and women (n=9) 75% participated in the pilot testing of the SPS. The ages ranged from between 18 and 75 years old, and the education level ranged from 12th grade to college. The median family levels ranged from those who made less than $10,000 to those who made more than $50,000. Most of the group members classified themselves as Baptist (80%), and the other members considered themselves nondenominational (2%), or Christian (18%).

The individual SPS mean score is 4.94, and the family group SPS mean score is 5.14. The agreement mean scores were 5.7. After completing the SPS, the families were asked how they felt about completing the SPS questionnaire as a family and whether there was general agreement in answering questions or if there was disagreement. Table 3 provides four samples from their responses.

7.3 Phase II: Quantitative and qualitative data analysis of participants’ spiritual perspectives and spiritual comfort levels

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 13.0 was used to compute internal consistency estimates of reliability for the SPS and the SCLI. Values for the coefficient alpha were 0.92 for the SPS and 0.88 for the SCLI. This indicated satisfactory reliability. Most of the correlations among the SPS items were all positive, and the values were all greater than 0.30. Item # 4: “How often do you engage in private prayer or meditation” and item #5, “Forgiving is an important part of my spirituality,” have an inter-item value of 0.74. Table 4 present inter-item correlation matrixes for the SPS.

Some of the inter-item correlations for the SCLI were below 0.30. All correlations among the variables are positive; however, items # 4 and # 9 have an inter-item value of .16. Item # 4, “How comfortable are you about engaging in prayer or meditation with (a doctor or nurse for families, or a patient for the nurses)?” does have positive correlations above 0.30 with the other nine items. These results suggest that item #9, “My spiritual views have had an influence upon my seeking health care,” may need a slightly different scale or rewording. For example, item #9 could be reworded as, “I seek spiritual guidance prior and during my health care treatment,” or “When deciding upon health care, I seek spiritual guidance.” Table 5 present inter-item correlation matrixes for the SCLI.

An independent t- test was conducted to address Research Question # 1: Is there a significant difference in the spiritual perspectives of African American families and mental health nurses within the context of depression? And Hypothesis 1: There is a difference in African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual perspectives as measured by the spiritual perspective scale within the context of depression. The SPS scores show no significant difference among the families and the nurses, t(58) = 1.05, p = .29, and d = 0.26.

An independent t -test was also conducted to address Research Question # 2: Is there a significant difference in the spiritual comfort levels of African American families and mental health nurses related to incorporating spiritual interventions within the context of depression? and Hypothesis 2: There is a difference in African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual comfort levels as measured by the spiritual comfort level indicator within the context of depression. The test showed a significant difference in the SCLI scores among the families and the nurses, t(58) = 4.86, p = .000, and d = 1.25 (see Table 6), indicating that the African American families are more comfortable than the mental health nurses in regards to incorporating spirituality within therapy.

7.4 Data analysis of participants’ transcriptions

Research Questions #3 through #6 were addressed using Paul Colaizzi’s phenomenological method [30]. Key questions from the semi-structured interview guide were asked during the focus group interviews about spiritual perspectives and comfort levels within the context of depression. Colaizzi stated, “the success of phenomenological questions depends on the extent that they tap the subjects’ experiences of the phenomenon” ([30], p. 58). Table 7 presents an outline of Colaizzi’s procedural steps applied to this study.

Sources: [30], p. 48-71; Colaizzi (as cited in [31], 2007, p. 83); [31], 2007, pp. 75-99.

Significant statements were extracted from the participants’ descriptions or protocols to formulate meaning from these statements; repeating the prior step; organizing the formulated meanings into clusters of themes; and integrating results into an exhaustive description ([30], pp. 59-72). Extracting significant statements are done by going back to the descriptions or representative protocols and “extract from them phrases or sentences that directly pertain to the phenomenon of interest” ([30], p. 59). The researcher went back to the transcripts and extracted significant statements and phases that pertained to the participants’ spiritual perspectives and comfort levels. Tables 8 present a comparison of the families’ and the nurses’ significant statements that were identified from this study.

7.5 Formulation of meaning

The researcher and a master’s-prepared nurse practitioner who was familiar with the population under study separately extracted significant statements from the transcripts and formulated meanings. The researcher’s and the nurse practitioner’s formulated meanings were compared in order to generate a final set of formulated meanings. Clusters of themes were emerged from the formulated meanings that were common to the family and nurse participants’ descriptions of their experiences of spiritual perspectives and comfort levels within the context of depression.

7.6 Exhaustive description

The qualitative findings of this study are presented as themes from the descriptions of the participants. Four major themes were developed for the families, and four major themes were developed for the nurses. Table 9 presents the four major cluster of themes for the African American families and for the mental health nurses that were identified from this study.

8. Discussion

The results from an independent t-test support the hypothesis that there is a significant difference in African American families’ and mental health care nurses’ spiritual comfort levels as measured by the spiritual comfort level indicator within the context of depression. However, the results from the independent t-test showed no significant difference in the spiritual perspectives scores of the African American family members and the mental health care nurses. The families completed the SPS and the SCLI individually and with their family members. A single family informant approach limits the generalizability of conclusions because the data cannot automatically be related to findings from studies using multiple respondents [30-32]. Uphold and Strickland (as cited in [32]) state, “When one respondent gives his or her point of view, it is one person’s reality and cannot represent a quality or characteristic of the family unit or system” (Uphold & Strickland, as cited in [32]). Conversely, Ferketich and Mercer (as cited in [32]) made this discovery:

One family informant may provide important data on the relationship between family members. The major assumption is that the individual family member’s perspective is a valuable source of information about the family. When the basic focus is on the individual well-being, one family member may be the most appropriate source for data collection (p. 290).

During the focus group meetings, the participants were able to reflect upon their spiritual perspectives and comfort levels related to incorporating spirituality within the context of depression or other therapy. Colaizzi’s [30-32] phenomenological method was used to analyze the focus group data. The findings were presented as four clusters of themes for the families and four clusters of themes for the nurses. The themes for the families were (1) divine dimensions of self and others; (2) confident but concerned; (3) longing for spiritual connections, but self-reliant; and (4) occurrence less than hoped for. The themes for the nurses were (1) divine dimension of self and others; (2) some hesitancy but possible; (3) significant and open to exploration; and (4) occurrence depends on receptiveness. Saturation was reached by the end of the fourth focus group for the families and around the fifth focus group for the nurses. The researcher was able to recognize repetition in data. The last two focus groups for the families and nurses that proceeded beyond saturation served as confirmation of the findings. A second discussion occurred with the participants at various time frames after data were analyzed to validate meanings and themes that emerged from the qualitative portion of the study. Most of these discussions took place at the participants’ homes or over the phone for the families and at the places of employment for the nurses. The participants articulated that the descriptions were truthful to their experiences. Therefore, no new data were obtained.

The rigor of Colaizzi’s [30-32] phenomenological method allowed the researcher to become immersed in the descriptive data in search of common themes and create patterns of relationships shared by the phenomenon. The researcher used free imaginative variation to capture essential relationships between the essence of spiritual perspectives and comfort levels. This process involved careful study of concrete examples supplied by the families’ and nurses’ experiences and systematic variations of these examples in the imagination [30-32]. “In this way, it becomes possible to gain insights into the essential structures and relationships among the phenomenon” ([31], p. 86). Probing for essences provided the researcher with a sense for what was essential in the spiritual perspectives and comfort levels of the participants. The middle range theory that was generated for this study emerged from the essential relations of the participants’ descriptions. The middle range theory is the essential structures of spiritual perspectives and comfort levels of African American families and mental health nurses within the context of depression. See Figure 4 for schematic representations of the essential structures of spiritual perspectives and comfort levels from the participants in this study. The structures are in the form of pyramids, and each side of the pyramid represents the essential relations of the participants’ descriptions; they are leading to the peak of the pyramids. The peak of the pyramids presents the clusters of themes that illuminate the essence of the participants’ spiritual perspectives and comfort levels.

8.1 The families and the nurses spiritual perspectives

Spirituality and spiritual perspectives were described by the families and nurses in terms of their beliefs and personal experiences. Spirituality seemed to reflect dimensions of the self in relationship to God, a Higher Power, and others. The experiences that were shared, based upon these dimensions of self and spiritual activities such as praying, praising, and worshiping by oneself or with other individuals.

8.2 The families and the nurses spiritual comfort levels within the context of depression

Most of the family members reported being very comfortable incorporating spirituality in therapy. However, they were concerned about the health care providers’ spiritual perspectives or level of spirituality. The family members felt that if the health care providers are not on their spiritual level or do not accept their beliefs they would not be comfortable displaying their spiritual self. Nonetheless, they articulated a significant desire to incorporate spirituality within the context of depression. This outlook maybe the reason why the families’ overall comfort level responses from both the qualitative and quantitative results were higher than the nurses. One of the family members made the following statements:

“I would be very comfortable, but the therapist has to be ready for that. Like you have to have a spiritual connection with other people. I would like to have that but the therapist need to be on the same level as I am so we can connect. Because if I’m on a spiritual level, and he’s not, he’s not going to treat my spirituality…just going to miss the spiritual part of it.”

All but one of the family members who responded to the question referring to the importance of incorporating spirituality in therapy verbalized that it is important to incorporate spirituality within the context of depression. The one member who did not agree with this did so because she communicated that expectations of incorporating ones belief in theory may be asking for too much.

The nurses exhibited some hesitance toward incorporating spirituality within therapy. They did not totally dismiss the idea of incorporating spirituality into care, but expressed their discomforts due to job restrictions, various religious backgrounds, possibility of the existence of psychiatric illnesses, and not knowing if the client’s would be receptive to the idea. There were several nurses; however, who did report incorporating spirituality within their practice. Similar to the families’ responses, the mental health care nurses also expressed that it is important to incorporate spirituality within therapy. However, the actual spiritual activities depend on the client’s being receptive to the idea, the nurse’s comfort level, and the restrictions given to the employee.

9. Limitations

The family group scores were slightly higher than the family individual member scores on the both SPS and SCLI, which may be related to family members in some way influencing each other when completing the scales within the focus groups. On the other hand, when exploring the spiritual perspectives of the families and nurses, the researcher noticed a difference with the age variable. The family members were younger than the nurses (percentages). Finally, most of the participants were affiliated with a religious organization, which may have influenced the spiritual perspective scale results.

10. Conclusion and Implications for Nursing

This study concluded with the results of two instrument scores and eight clusters of themes that described the lived experiences of the participants’ spiritual perspectives and comfort levels within the context of depression. The quantitative and qualitative analyses revealed high spiritual perspectives for the families and nurses. However, the analyses also suggest significant differences in the families’ and nurses comfort levels in regard to incorporating spirituality within therapy. Although the nurses’ in this study had comfort levels that were lower on both of the quantitative andqualitative analyses, several of them reported implementing spiritual interventions within their practice(s), and many of them stated that it is important to incorporate spirituality into therapy.

In theory testing and theory generating, the families identified depression and other illnesses that could be managed or partly eliminated by relying on their spiritual beliefs. Family members also stated the importance of medication and other treatment compliance. Reflecting upon the Neuman Systems Model as it relates to this study, depression is a stressor that can possibly penetrate a family system’s lines of defense. An implication for nursing is realizing that the family’s spiritual perspectives and comfort levels can help promote wellness within the context of depression. Nurses working with families can encourage them to use their spirituality as primary, secondary, or tertiary preventive measures. Whether the clients are practicing Baptists, Methodists, agnostics, or atheists, they will most likely find spiritual values to be important. It is important for nursing to know that studies examined the concept of spirituality found that a person who considers himself or herself to be agnostic or atheist may possess a strong belief in significant relationships, self-chosen values, and goals instead of a belief in God. This belief may become the driving force for the lives of these individuals [34].

Spirituality is believed to have an influence on individuals from various ethnic groups. Therefore, assessment of spirituality as it relates to health and comfort is relevant. Nurse educators and researchers should include more creative content related to spiritual care. Something that was learned from this study was that both the nurses and the clients may feel that it is important to incorporate spirituality within therapy, but both parties fear taking the first step. The nurses can take that first step through spiritual assessment. Pargament [35] eloquently stated:

When people walk into a therapist’s office, they don’t leave their spirituality in the waiting room. They bring their spiritual beliefs, practices, values, and struggles along with them. Yet many therapists find themselves unaware of or unprepared to deal with this dimension of a client’s experience (p. 1).

11. Recommendations for Further Research

Several topics for further research emerged from this study. Although this study focused on African American families’ and mental health nurses spiritual perspectives and comfort levels, any study like this would benefit nurses incorporating spiritual perspectives in therapy across the age continuum and among various ethnic groups. A recommendation for further research is testing the theoretical framework [17] designed to encourage spiritual expressions while addressing nurses comfort levels. The philosophical claims undergirding the theoretical framework are derived from the Neuman Systems Model and Symbolic Interaction Theory. Nursing students and faculty members at Norfolk State University in Norfolk Virginia have planned an outreach initiative for population health which included testing the framework [17]. Furthermore, the students presented the initiative as a research proposal at the annual Virginia Department of Health Equity Conference on October 17, 2018 (see figure 5 and supplementary files 1 and supplementary file 2 ). This initiative aims to explore the impact of this spiritual comfort (SC) framework [17] designed to: 1) increase spiritual comfort levels among nurses and other health care professionals within their practice; 2) stimulate spiritual involvement on indicators of population health [36] for African Americans within the context of depression.

Competing Interests

The author declare that there is no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Lydia Figueroa was responsible for the study design, ethics in research, data collection, analysis of data, and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledge God, family, study participants; Dr. Spencer Baker, Dr. Bertha Davis, Dr. Janet Colaizzi; Dr. Danna Saunders; Dr. Pamela Reed; Dr. Betty Neuman; Mr. Johnathon Vasaturo; Mrs. Melody Armstrong; Mrs. Marie McCarson and all nurse scholars who helped make this process successful - Thank you.