1. Introduction

Pain is sensory quality as well as by other sensually perceived sensations. In its acute form provides a biologically useful information to the human body which means recognizing the source of danger, localization of damage resulting in elicitation necessary to avert imminent danger or healing the resulting damage. Chronic pain (lasting longer than three months) has no biologically useful function and is a source of biological, psychological, social and spiritual suffering of any individuals. The pain fully classified as prolonged must meet the following criteria: primary disease is treated with lege artis with no signs of progression, pathomorphological base of primary disease does not explain the pain adequately, in pathomorphology terms the pain could not be determined. Shortterm pain can be also classified as chronic if it goes beyond the period for the disease or related to the usual failure.The pain fully classified as prolonged must meet the following criteria: primary disease is treated with lege artis with no signs of progression, pathomorfological base of primary diseas does not explain the pain adequately, in pathomorphology terms the pain could not be derermined. Shortterm pain can be also classified as chronic if it goes beyond the period for the disease or related to the usual failure [1]. Chronic pain with its negative impacts affect the daily life of individuals - reduces the ability to perform daily activities, reduces mobility, leads to loss of self-sufficiensy with a gradual depending on the others help, causes changes in behavior and thinking and then changes human relations leading to social isolation. Experiencing the chronic pain negatively affects not only the patient but also his entire family. Therefore, it is necessary to deal with the patient´s quality of life in general and the broader context [2]. The quality of life and pain currently belongs to the more frequently mentioned phenomena also in relation to the care of the oldest people [3]. It is appropriate to reflect on the question of their life quality with the fact of the increasing mean and maximum lifespan. Currently it is obvious improvement of functional status of elderly population and this trend is also apparent in their future peers. Health is still considered one of the most important human values. Despite the fact that people are going to live longer and in better health and functional condition, they are more educated and more active, it will occur due to the general characteristics typical of the senior age the series of restrictions that are hazardous to the lives of seniors. The most limiting issues could include the loss of autonomy, with the gradual development of dependency, retirement, family relationships, loss of a life partner, loneliness, retirement in an institution, etc [4]. The spotlight on issues of life quality gets evaluation and analysis of well-being, quality of life, satisfaction and happiness. From a subjective point of view the quality of life associated with psychological well-being and general satisfaction of life.

Against it the objective quality of life means meeting the requirements relating to the social and material conditions of life and physical health [5].

1.1 Goal of the study

The main aim of this prospective study without a control group, using participatory observation and objective assessment is an evaluation of the quality of life for the selected group of elderly with chronic nonmalignant pain living in residential social services. The intention was to examine selected areas of biological, psychological and social dimensions of life quality by elderly people living in residential homes for the elderly with chronic nonmalignant pain.

2. Materials and Methods

For the purpose of the study the prospective study using participatory observation and objective assessmentwas chosen. Data collection for the assessment study was based on a combination of items selected from a standardized questionnaire WHOQOL 100 [6], supplemented by items aimed at the socio-demographic data of respondents and objective and standardised assessment scales: Yesavage test for evaluation of depression (Geriatric Depresion Scale–GDS) [7], Test of congitive functions (MMSE - Mini Mental State Examination) [8] and functional activity questionnaire (FAQ - Functional Activities Questionnaire)[9,10].There was a deliberate choice of respondents usedin the study– respondents had to meet the following criteria: age 60 years and older, place of residence in social service facilities (Residential homes) with a minimum length of six months, the presence of chronic nonmalignant pain (verified from the documentation) on visual analogue scale (VAS ) [11] higher than 4 (on a ten point scale), and the willingness and capacity to participate in the questionnaire survey including the use of objectifying test GDS. Data were evaluated through the program SPSS (IBM Predictive Analysis Software) statistic version 19 using chi-square test, Kruskal Wallis test and Kendall Tau at the 5% significance level.

3. Results and Discussion

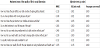

There were 400 seniors identified and addressed who meet the requirements and specified criterion for inclusion in the study. Finally 155 seniors were evaluated using the tools described above (from the number originally addressed 38.5%). The resulting number of evaluated seniors was potentially negatively affected by the objective requirements imposed on the set of respondents and positively by the full assistance of researcher at collecting information needed to analyze the data (especially objectifying evaluation probands). From a total of 155 (100%) elderly respondents participated in the study there were 121 women (78.1%) and 34 men (21.9%). At the study time there were 101 (65.2%) of respondents widowed, 26 respondents (16.8%) divorced, 18 respondents (11.6%) single and 9 responents (5.8%) married.

Only 1 respondent (0.6%) said he lives with a partner without marriage. In terms of cohabitation most respondents (n=63;40.6%) shared a room with one other person and 61 (39.4%) of the respondents lived in the own room alone. Only 10 respondents (6.5%) shared living with two people and 5 respondents (3.2%) lived with a spose/ partner/husband/wife. 16 respondents (10.3%) marked another way of coexistence, they shared the room with another 3, 4 or 5 person. For more information see the table 1.

One of the basic assumptions in our study was that selected sociodemographic dererminants (age, sex, education, marital status, cohabitation) and applied objectifying measuring tools (GDS, MMSE, FAQ, VAS) in relation to selected areas of biological, psychological and social dimensions quality of life observed in connection with chronic ninmalignant pain depend on each other. Psychological dimension belonged to one of the many areas monitored quality of life. There was no statistically significant relationship (Kruskal - Wallis test, p=0.830) between age and declared feelings of sadness and depression due to pain in the monitored group of seniors. It has not been identified as significant (chi-square test, p=0.285) as well as education. The findings in relation to education was surprising, we assumed finding a significant relationship due to the fact that education plays a role in the ability to find appropriate solutions and strategies of coping, mental endurance and possibly seek professional help when people suffer from pain. Also the marital status of seniors in our reviewed patients group unrelated with declared feelings of sadness and depression due to pain (chi-square test, p=0.749). We built a gererally known fact that marital status is one of the dominant social factors. The reported incidence of depression by married men is lower than by single men but higher by the married women then single [12]. The highest intensity of occurrence of sadness or depression in our seniors group (very much/maximum) in the context of pain was reported by respondents living in pair 40.0% (divorced 38.5%, widowed 33.7% and single 16.5%). With age, it is also possible to observe the increasing rise of stressors. This is because the person often loses the closest people, changes socio-economic role, suffers from a number of chronic somatic diseases including the occurrence of number of chronic pain, may lose self-sufficiency, it could lead to placed in longterm care, etc. [13] The study was conducted among institutionalized person with potentially higher risk of dysphoric manifestations and depression but most of them were widowed or divorced (82%) and because of it statistically significant difference validation was impossible.On the contrary the depression feeling was confirmed statistically significantly more frequently by women with chronic pain then by men (chi-square test, p0.045). Women most often (37.2%) declared, that feeling of sadness or depression related to pain felt „very much/maximal“. This result was observed only in 17.6%by men. Medium perceived intensity of occurrence feels sad or depressed in relation to pain was recorded in a relatively equal representation for women (30.6%) and men (29.4%). Non or minimally occurrence of sadness or depression was cited by 32.2% of women and 52.9% of men. Our result corresponds to the information previously presented in professional resources. Gender is among the risk factors and predisposing the development of depression in older patients. From the statistical point of view women suffer from depression about twice often than men (lifetime prevalence is around 20%). The prevalence of depressive episode in the elderly population (over 65 years) is presented in 1.4% of women and 0.4% of men. Although this finding is less than in general population (lifetime prevalence of depression ranges from 5 to 16%). In the adult population the risk of depression is reported between 5-16% and the prevalence in the elderly is frequently reported around 10%, however, this value fully concerns expressed depressive symptomatology meeting all the criteria of depressive phase. If there is an active search for depressive symptoms in the elderly including the incompletely expressed depressive states, the value is around 15-25% [14]. Significantly higgher risk of depression can be found in the elderly somatically ill or institutionalized person [15]. Again we can talk about the agreement between our findings and professional resources. Tse et al. found in their study that pain had a significant impact on the seniors mobility and Activities of Daily Living test (ADL), and also positively correlated with happiness and life sarisfaction but negatively correlated with loneliness and depression [16]. He had previously reported this fact on a study conducted in Netherland [17]. In the case of evaluation of the incidence of depression in-+ elderly subjects living in residential social services with chronic nonmalignant pain according Yesavage (GDS), in relation to all monitored areas of psychological quality of life dimensions the statistically significant relationships were verified because Kendall's Tau significance test did not exceed the critical value 0,05. It was confirmed in testing that increasing pain worsens symptoms of depression and reduces ability to concentrate by seniors. The pain is a significant factor that affects the perception of seniors. The vigilance ability (keeping overall ability to focus and its concentration) is gradually involutionaly reduced with increasing age. The most common influencing factors include for example fatigue (older people get tired faster and more often, which requires much more time for regeneration) [18]. The chronic type of pain or the occurence of pain vague affects cognitive awareness and subsequently attracting attention [19]. The effectiveness of the attention seniors also depends on situational context or type of task. Concentration of attention varies much less and the major changes will not happen if we talk about simple or well-known work and seniors performs it almost automatically especially if seniors are not under effects of disturbing sounds around. The quality of focus is also an important indicator of overall level of cognitive functioning [20]. Also, as we could see above, the pain influence on eldest concentration should not be downplayed or underestimated. It is evident from our results that the test according Yesavage has a high ability to identify mental status changes related to seniors and it is related to subjectively perceived quality of life by seniors with chronic nonmalignant pain. During evaluating the quality of life in the biological dimensions there were found marked differences in the subjective evaluation of pain in relation to the effect of the incidence of daily living pain. The pain and its daily life activities impact was much more positively perceived and evaluated by elderly they did not feel subjectively perceived pain or this pain did not reach mean values (54.2%). Our found differences may be caused and affected both seniors affected comorbidities and also pain experiencing, self-sufficiency achieved degree or social climate in a home for the elderly [21, 22]. Another significant differences were found in the evaluation of the selected areas of biological dimension and depression scale for geriatric patients (Table 2) and the questionnaire evaluating the functional activity (FAQ) in relation to the assessment of the impact of pain on sleep and pain management or discomfort feelings. (p0.002). While we were selecting the objectifying tests for our study we followed the actual targets of current geriatric science. These include: achieving the highest activity, functional fitness, self-sufficiency and independence in a patient usual area, cotributing to keep the life quality related to health condition etc. [23] That is why we were interested in the fact how much could be this area influenced.

Also in the last assessment concerning social dimension, several significant differences were found in subjective pain perception in relation to the occurrence of loneliness (p0.000). It is evident, of the total out the percentage respondents reactions, that seniors (59.4%) perceived the pain associated with the occurrence of loneliness within intensity little/non. The percentage of respondents decreases with higher degree of subjective perception of pain in relation to the loneliness occurrence. This difference is due to the findings of the current subjective pain in elderly patients (incidence rate identified by the pain intensity). In the professional literature there can be found divided opinion on the increased or decreased sensitivity to pain in seniors. There has been some decline in the elderly population in the area of nociception, which can lead to the affecting the protective function in some acute diseases. Increase in the psychogenic component in chronic pain leads to a reduction in tolerance to long term pain [24]. Another very interesting results (p0.000) were found in testing items involved in the assessment of health status in relation to the impact of pain on the pursuit of hobbies and leisure time activities. The percentage of respondents in the study group is higher (41.9%) if they perceive and then describe the intensity of influence (in the form of very much/maximum) of subjective evaluation of health status in relation to the pursuing hobbies and interests with regard to the pain. About 25.8% of seniors said their are influenced by pain in relation to doing their hobbies, on he other hand 32.3% of respondents marked low or no pain influence. These results could be relatively logically predicted.

The less complicated health condition or less disease, the better ability to handle the daily living activities (self-care and independence) or even capable of adequate choice of various interest, hobbies or activities. To fully map the potential impact of selected objectifying measuring tools of all dimensions of seniors life quality living in homes for the elderly with chronic nonmalignant pain the last monitored was the social area. It was possible to find a number of specific statistically significant relationships (Table 3).In summary we could say that in relation to the areas of cognitive and mental functioning theremay occur perception of greater pain in relation to increasing feelings of loneliness and vice versa. In the physical realm was verified that pain is affecting daily activities, hobbies, loneliness and the daily routine, shortly said it affects everyday activities. In all monitored areas of social quality of life the pain affects psychological well-being and the occurrence of sadness or depressive symptoms according to the GDS.

We believe that the results arise from the merging of all areas within a holistic view of a human which can not be separated. To adequately function the human body needs a security for many everyday activities (personal or instrumental). Despite the fact that seniors have secured a health and social care in the home for elderly, we cannot neglect their personal meaning. Meeting human needs (especially higher), the adequate eveluation and adjustment of pain therapy is the necessary assumption for ensuring the quality an dignified life. The studies results of the seniors life quality with chronic nonmalignant pain living in Residential homes for elderly reaffirmed the need to focus on repeated and continuous screening in all dimensions of qualityof life. It was confirmed that chronic nonmalignant pain is a very negative risk factor and syndrome, which is a very significant presence also on the degree of satisfaction of biological needs and influencing psychological and social dimensions of seniors quality of life. Equally important was the finding in the use of objectifying evaluation and measurement techniques. Their importance was confirmed in the evaluation of functional and health condition of the elderly people in the not only the input context but continuous diagnostic screening. The objectifying tests can clearly be used as a basis for assessing the prognostic factors in the development of actual physical and psychological state of seniors. It was also confirmed that it is necessary when health monitoring to match the subjective and objective assessments to achieve an adequate comprehensive evaluation.

4. Conclusion

On the bases of the realized prospective study conducted among elderly people living in residential social services (Residential homes), it was clearly identified impact of chronic nonmalignant pain on quality of life in selected areas of biological, psychological and social dimensions. It was found that the psychological condition influenced the perception of chronical nonmalignant pain in elderly people (seniors) living in Residential homes in relation to the quality of life, this score was with using a scale of depression according to the Yesavage (Geriatric Depression Scale - GDS). And next the test for cognitive ipairment (Mini Mental State Examination - MMSE) and functional activity questionnaire (Functional Activiries Questionnaire - FAQ) of selected items showed the statistically significant association in relation to sleep and the feeling of loneliness. Results of the study revealed the need of high frequency effective monitoring of the life quality and diagnostic current health and functional condition of seniors with chronic nonmalignant pain living in Residential homes, through objectifying evaluating and measuring techniques (in prarticular using FAQ, GDS, MMSE, QoL). Equally important is the need for effective pain management in order to support self-sufficiency and independence of seniors. Although the majority of elderly (seniors) did not at first decrease a clear chance in the monitored selected areas of biological, psychological and social dimensions of quality of life. During the through assessment there was found the high correlation in the evaluation of the quality of life according to the selected items WHOQOL - 100 mainly in relation to the objective Geriatric Depression Scaletest (according Yessavage).

Limitation of the Study

The authors are aware that the main limitation of the study is the number of involved elderly from one cultural background and this is also the reason for citation of culturaly appropriate literature– for more general conclusion further research is needed.

Competing Interests

All of those authors certified that there is no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design (AP, MS), data collection (MS, AP) data analysis and interpretation (AP, MS), manuscript draft (AP, MS), critical revision of the manuscript (AP, MS), final approval of the manuscript (AP).

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank to all involved elderly for their involvement and acceptation of the researchers during the study and management of Residential homes for their approval of the study, kind attitude and acceptation.

Ethical Aspects and Conflict of Interest

The study methodology (protocol for obtaining data) was designed and administered according to ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2002). Completing the protocol was taken as indicating consent to participation in the study which was allowed by the local ethical commetties and/or by managers in each Residential homes. The participants could withdraw from the study at any time.