1. Introduction

Due to early cancer detection and improved cancer treatment technology, the survival rate of cancer patients has increased remarkably, especially in gynecological cancers, and there has been more interest in gynecological cancer patient's quality of life after completing anti-cancer treatments. With regard to the survival rates of various types of gynecological cancers, breast cancer shows the highest 5-year survival rate (91.3% compared to the other main types of cancer), and the rate is still rising [1]. However, many cancer patients fear the reoccurrence of cancer, and some even have emotional disorders, such as depression. Therefore, it is important to consider quality of life and not only evaluate the effect of cancer treatments with survival rates. Research should address cancer patient's physical, mental and social wellbeing as their survival rates increase [2].

To women, breasts are a symbol of femininity and represent womanhood and beauty and are part of nurturing children [3]. However, diagnosing breast cancer already initiates a fear of cancer by not only causing patients to suffer from psychological distress but also causing physical damage (e.g., mastectomy). Cancer also causes various problems related to sexuality, such as having a reduced feeling of femininity and having decreased interest from their spouse, and their self-esteem and wellbeing are negatively affected [4]. Surgeries and treatments provided to gynecological cancer patients, such as anti-cancer chemical therapies and radiotherapy, are accompanied by various adverse effects. Depending on the type of cancer and the surgery, some patients must have a substantial section of their vagina or breast removed, and because of anti-cancer chemical therapies, some patients even experience vaginal dryness and dyspareunia [5].

As a direct and primary support system for patients to overcome disease-caused difficulties, spousal emotional support is helpful [6], and sexual intimacy is an important factor for determining either happy or unhappy marital relationships. Specifically, a satisfactory sexual life plays an important role in married couple's relationships, reinforcing their marital bond and having positive effects on their marital satisfaction and intimacy. Their affection and intimacy is a fundamental factor for sustaining their marital relations [7]. Accordingly, anti-cancer treatments or operations are recognized as major issues for gynecological patients and their spouses, and currently, intimacy has become an important factor that affects quality of life during treatment. Most research that investigates gynecological cancer patients is focused on the actual states of gynecological cancer patients' sexual lives or their sense of loss or depression after operations [8,9], but few studies have studied the correlation between sexual life, marital intimacy and depression in gynecological cancer patients.

Therefore, this study aimed to provide basic data for nursing interventions to improve gynecological cancer patient’s quality of life by investigating their sexual lives and the relationship between marital intimacy and depression in breast-cancer patients and uterine-cancer patients, who can be diagnosed early and have higher survival rates amongst all gynecological cancer patients.

The purpose of this study was to improve marital relationships and the quality of life in gynecological cancer patients by verifying the correlation between their sexual lives, marital intimacy and depression. The study’s concrete objectives are described below.

First, we wanted to confirm the general characteristics of the research subjects. Second, the sexual life of the research subjects needed to be well understood. Third, marital intimacy of the research subjects also needed to be understood. Fourth, we wanted to investigate depression in the research subjects. Finally, we wanted to comprehend the correlation between the research subjects' sexual life, marital intimacy and depression.

2. Research Hypotheses

First, there will be a change in the sexual behavior attitude of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses after operations.

Second, there will be a change in the sexual behavior characteristics of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses after operations.

Third, there will be a change in the marital intimacy of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses after operations.

Fourth, there will be the correlation between the research subjects' sexual life, marital intimacy and depression.

3. Materials & Methods

This study used a descriptive correlation design to investigate the potential correlation between sexual life, marital intimacy and depression in gynecological cancer patients.

3.1 Subjects

This study selected patients who were diagnosed with gynecological cancers at K University Hospital, located in Seoul, Korea, and were still receiving follow-up treatments as outpatients after cancer operations and anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy. We also included their spouses.

The gynecological cancer patients were aware that they had gynecological cancer, were aged 30 to 60 years, were married women living with their spouses, understood the purpose of this study and agreed to participate in this study.

Their spouses were married men living with these gynecological cancer patients, understood the purpose of this study and agreed to participate in this study. Data were collected from April 20 to May 23, 2010, from research subjects who were diagnosed with gynecological cancer, got after operation and received treatments as outpatients at K University Hospital in Seoul, Korea. After an explanation was provided regarding the purpose and procedures of the study, the subjects were asked to agree to participate and to complete a structured questionnaire. If the participant did not understand the content of the questionnaire, the researcher directly interviewed the participant. There were a total of 153 research subjects, including 119 gynecological cancer patients and 34 spouses.

3.2 Research tools

Sexual life measurement tool: This study used the Sexual Life State Measurement Tool for Cancer Patients, modified and complemented by Kim [9]. The questionnaire consisted of 4 questions about sexual behavior attitude(Anxiety about sexual problems, Sexual stress from spouses, One’s or spouse’s avoidance of sexual life) and 4 questions about sexual behavior characteristics (Change of sexual desire, Degree of having sex, Degree of caressing body parts or genitals, Degree of masturbating).The first 4 questions were based on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 - ‘Not at all’, 2 - ‘A little’, 3 - ‘Relatively yes’ and 4 - ‘Definitely yes’. A higher score indicated a more negative attitude. The second 4 questions were analyzed with real numbers and percentages, and a higher score indicated a greater frequency of sexual behavior. Cronbach’s α of sexual behavior attitude was .92 and Cronbach’s α of about sexual behavior characteristics was .91.

Marital intimacy measurement tool: Warring & Reddon [10] developed the Marital Intimacy Questionnaire, which Kim [11] modified and complemented. This study used 8 questions from this questionnaire as a measurement tool. This tool uses a 4-point Likert scale: 1 - ‘Not at all’, 2 - ‘A little’, 3 - ‘Relatively yes’ and 4 - ‘Definitely yes’. A higher score indicated stronger intimacy. Cronbach’s α of this tool was .86 in this study.

Depression measurement tool: This study used Beck’s Depression Inventory (1967) [12], adapted by Lee [13].The BID is composed of 21 questions, including emotional, cognitive, physiological and physical symptoms of depression. This tool is based on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 points for the most stable psychological state to 3 points for the most negative psychological state, and the total score ranges from 0 to 63.A higher score indicates more severe depression.Cronbach’sα of this stool was .93 in this study.

3.3 Data analysis

This study analyzed the data using SPSS/Win 12.0. The characteristics of the research subjects were calculated with frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. To investigate changes in the sexual life and marital intimacy of the research subjects before and after operations, this study used t-tests and ANOVA. To investigate the correlation between sexual life, marital intimacy and depression, we conducted a correlation analysis.

4. Results

4.1 General characteristics of research subjects

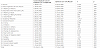

We analyzed the participants’ general characteristics, including age, educational level, religion, financial state, burden of medical expenses and satisfaction with marital life. The results are shown in Table 1.

There were a total of 153 research subjects, including 119 gynecological cancer patients and 34 spouses. Regarding education level, 50.4% of the gynecological cancer patients were high school graduates followed by middle school graduates, and of their spouses, high school graduates accounted for 32.4%. A total of 38.7% of the gynecological cancer patients were Christian. Regarding monthly income, 33.6% of the gynecological cancer patients earned below 1 million won, and 73.1% were unemployed, whereas 26.9% were employed. Of their spouses, 35.3% earned more than 3.01 million won per month, and 70.6% were employed. A total of 66.4% of the gynecological cancer patients had purchased cancer insurance.

Among all of the gynecological cancer patients, 52.9% had uterine cancer, and 47.1% had breast cancer. Regarding satisfaction with marital life, most patients responded ‘Alright’ followed by those who responded ‘Relatively unsatisfactory’ of their spouses, the majority responded ‘Relatively satisfactory’.

4.2 Sexual life of subjects before and after operation

4.2.1 Sexual behavior attitude of subjects before and after operations

The average sexual behavior attitude score of the patients was 5.92 before the operation and 8.75 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change, whereas their spouses’ mean sexual behavior score was 6.24 before the operation and 9.62 after the operation, which also shows a significantly negative change (Table 2 and Table 3).

Among the questions about sexual behavior attitude, the average score on ‘Anxiety about Sexual Problem’ was 1.45 before the operation and 2.15 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change. The average score on this item among the spouses was 1.85 before the operation and 2.59 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change.

In gynecological cancer patients, the average score on ‘Sexual Stress from Spouses’ was 1.56 before the operation and 2.13 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change, whereas the average score among spouses was 1.76 before the operation and 2.53 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change. The average score on ‘One’s Avoidance of a Sexual Life’ was 1.50 before the operation and 2.45 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change. The average score on this item among spouses was 1.24 before the operation and 2.03 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change.

4.2.2 Sexual behavior characteristics of subjects before and after operation

The overall average of sexual behavior characteristics in the gynecological cancer patients was 7.54 before the operation and 4.38 after the operation, which shows a significantly negative change, and the spouses’ average score was 8.26 before the operation and 5.91 after the operation, which also shows a significantly negative change (Table 4 and Table 5).

Among the sexual behavior characteristics, the average score on ‘Change of Sexual Desire’ was 2.04 before the operation and 1.50 after the operation among the cancer patients, which shows a significant reduction. Spouses’ average score on this item was 2.12 before the operation and 2.16 after the operation, which shows no significant difference.

The average score on ‘the Degree of Having Sex’ was 2.94 before the operation and 1.44 after the operation, which shows a significant reduction, whereas the average score among spouses was 2.889 before the operation and 1.38 after the operation, which shows a significant reduction. The average score on ‘the Degree of Caressing Body Parts or Genitals’ was 2.39 before the operation and 1.18 after the operation, which shows a significant reduction. The average score on this item among spouses was 2.71 before the operation and 1.24 after the operation, which shows a significant reduction.

4.2.3 Marital intimacy of research subjects before and after operation

The average marital intimacy score among the patients was 20.65 before the operation and 20.19 after the operation, which shows a significant difference, whereas the average score among the spouses was 19.74 before the operation and 19.76 after the operation, which shows no significant difference (Table 6 and Table 7).

Among the questions about marital intimacy, the average score on ‘Making Sexual Expressions Freely’ was 2.24 before the operation and 1.79 after the operation among gynecological cancer patients, which shows a significant difference. The average score on this item among the spouses was 2.06 before the operation and 1.67 after the operation, which shows a significant difference as well.

In gynecological cancer patients, the average score on ‘Expression of Feelings of Love to Each Other’ was 2.39 before the operation and 2.33 after the operation, which shows no significant difference. The spouses’ average score on this item was 2.29 before the operation and 2.09 after the operation, which shows no significant difference. The average score on ‘Spending Daily Life and Leisure Activities Together’ was 2.46 before the operation and 2.75 after the operation, which shows a significant difference. The average score on this item among the spouses was 2.29 before the operation and 2.56 after the operation, which shows a significant difference. The average score on ‘Respecting Each Other’ was 2.67 before the operation and 2.82 after the operation, which shows a significant difference. The average score among the spouses was 2.67 before the operation and 2.82 after the operation, which shows a significant difference. The average score on ‘Solving Conflicts through Communication’ was 2.61 before the operation and 2.72 after the operation, which shows a significant difference. The spouses’ average score on this item was 2.53 before the operation and 2.56after the operation, which shows no significant difference. The average score on ‘Having a Stable Marriage Life’ was 2.90 before the operation and 2.47 after the operation, which shows a significant difference, whereas the spouses’ average score was 3.03 before the operation and 2.32 after the operation, which shows a significant difference.

4.2.4 Correlations among sexual life, marital intimacy and depression

In investigating the correlation among sexual behavior attitude, sexual behavior characteristics, and marital intimacy among the relationships between sexual life, marital intimacy and depression, there was a positive correlation between sexual behavior attitude and depression before operations. Specifically, the more negative the sexual behavior attitude was before the operation, the greater the depression (Table 8). There was also a positive correlation between behavior attitude and depression after operations. The sexual attitude after the operation showed a positive correlation with the sexual characteristics before the operation; therefore, the more negative their sexual attitude was after the operation, the higher their sexual behavior characteristics. There was also a positive correlation between sexual behavior attitude after the operation and sexual behavior characteristics; therefore, the more negative their sexual behavior attitude was after the operation, the higher the sexual behavior characteristics.

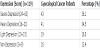

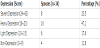

4.2.5 Depression of research subjects

Based on a maximum BDI score of 63 points, the gynecological cancer patients and their spouses had average BDI scores of 21.65 and 17.63, respectively (Table 9).

With regard to differences in each question, there was no significant difference in 'Sorrow' between gynecological cancer patients (1.08) and their spouses (0.91), and there was no significant difference in 'Discouragement for the Future' between the patients (1.00) and their spouses (0.82). There was no significant difference between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses on the item 'A Feeling of Failure' (0.85 and 0.65, respectively) or 'Discontent with their Daily Life' (1.01 and 1.03, respectively). There was no significant difference between gynecological cancer patients on the items 'A Feeling of Guilt' and 'A Feeling of Being Punished'. On the items 'I Hate Myself ', 'Accepting Mistakes' and 'Suicidal Impulse', there were no significant differences between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses. However, there was a significant difference between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses on the item 'Crying'. On the items 'Irritation', 'Interest in Others' and 'Making Decisions', there were no significant differences between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses. However, there was a significant difference between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses on the items 'Change in Appearance' and 'Start with Job'. There were no significant differences between gynecological cancer patientsand their spouses on the items 'Change in Sleeping Habits', 'Fatigue' and 'Appetite'. There was a significant difference between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses on the items 'Losing Weight' and 'Concern about Health'. Finally, there was a significant difference between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses on the item' Interest in Sex' (1.51 and 0.91, respectively).

70.6% of the gynecological cancer patients had heavy depression and 70.6% of their spouses had heavy depression (Table 10, 11). Therefore, both the gynecological cancer patients and the spouse receiving the gynecological cancer surgery can be seen that there is a need to be proactive nursing a serious depressive state.

5. Discussion and Hypothesis Verification

5.1 Hypothesis 1

In analyzing the sexual behavior attitudes of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses before and after the operation, we found that both gynecological cancer patients and their spouses changed their sexual behavior attitude negatively after the operation. Therefore, our hypothesis was supported.

This finding occurred because the research subjects changed in a negative way in terms of anxiety about sexual problems, one's avoidance of a sexual life and spouse's avoidance of a sexual life.

Husbands avoided a sexual life because they feared that they might worsen their wives' physical conditions, and they even avoided expressing their feelings and concerns. During this process, they experienced mental and physical symptoms, such as diarrhea and stomachache [14]. Due to these stressful factors, their sexual stress changed in a negative way.

5.2 Hypothesis 2

In analyzing the sexual behavior characteristics of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses, we found that both gynecological cancer patients and their spouses showed a reduction in sexual behavior characteristics after the operation. Therefore, our hypothesis was supported. Of all of the sexual behavior characteristics of gynecological cancer patients, 'Sexual Desire', 'Sex Frequency' and'A reduction in the frequency of caressing genitals' reduced the most after operations.

Breast cancer patients are ashamed of not having breasts; therefore, they tend to not have sex with their husbands. Considering that women's sexual lives are different from men's and that it is greatly influenced by emotional relationships and psychological reactions, unlike men, it is necessary to help women properly adapt themselves to their altered bodies after their operation, thereby restoring their sexual lives and positive self-images.

5.3 Hypothesis 3

In analyzing our hypothesis 'There will be a change in the marital intimacy between gynecological cancer patients and their spouses after the operation, we found that marital intimacy reduced to 0.34 points, but there was no significant change. Therefore, this hypothesis was rejected. There was no difference in marital intimacy scores after operations, but some differences were found in each question. The average scores on 'Making sexual expressions freely' and 'having a stable marriage life' changed significantly in a negative way after the operation. Accordingly, a marital relationship enhancement program needs to be developed so that patients and their spouses better understand each other and provide more affection and intimacy to improve their marital and sexual communication.

5.4 Hypothesis 4

Sexual behavior attitude, sexual behavior characteristics and marital intimacy of gynecological cancer patients showed a positive correlation with sexual behavior attitude and depression before operations. Specifically, the more negative their sexual behavior attitude was before their operation, the higher their depression. Additionally, sexual behavior attitudes after operations showed a positive correlation with depression, which reveals that a more negative sexual behavior attitude after the operation indicate the greater degree of depression. Sexual behavior attitude after operations showed a positive correlation with sexual behavior characteristics before operations.

Therefore, the marital relationships of gynecological cancer patients and their spouses need to be carefully addressed to minimize their sexual life difficulties caused by the diagnosis or treatment of gynecological cancers. Considering the various forms of treatment and the adverse effects that cause many problems in the sexual life of gynecological cancer patients, we should provide patients and their spouses with information, support and consultations to improve their sexual life.

It is necessary to evaluate depression throughout cancer treatment period in gynecological cancer patients, and our findings imply that we need effective depression interventions that can reduce the degree of depression in patients who develop depression.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the sexual behavior attitudes of gynecological cancer patients changed negatively after operations, and their sexual behavior characteristics also reduced with a higher degree of depression after operations.

Accordingly, it is essential to prepare measures that can change the sexual behavior attitude of gynecological cancer patients in a positive way and help manage their marital relationships. Additionally, it is necessary to develop an education program for gynecological cancer patients and their spouses before and after operations to prevent and reduce factors that negatively affect their marital relationships and to help them increase their quality of life.

Based on this study’s results, a longitudinal study on the changes in the sexual life and depression of patients after operations needs to be conducted, and nursing interventions for gynecological cancer patients to reduce depression and to enhance sexual life need to be established. An education program should be developed for gynecological cancer patients and their spouses before and after their operations.

Author Contributions

Boonhan Kim and Eunju Jang designed the study and performed the experiments, Dongsuk Lee and Hwajung Kang performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest’s exits.