1. Introduction

The increase of antibiotic resistance in gram negative bacteria is of worldwide concern. Most prominently, resistance to oxyimino cephalosporins is mediated by Extended Spectrum beta-Lactamases (ESBL), which are often localized on mobile genetic elements like plasmids. Concomitantly with resistance against cephalosporins, these strains are often also resistant against non-beta-Lactam antimicrobials [1].

The molecular epidemiology of ESBLs is complex. Most the enzymes are from the Temoneira (TEM), sulfhydryl variable (SHV), and cefotaximinase (CTX-M) families, but several other ESBL families have also been described. Even within these families, heterogeneity is substantial, with 192 SHV genes, 231 TEM genes, and 166 CTX-M genes described to date (http://www.lahey.org/studies, accessed on Apr 10, 2015).

A proper understanding of ESBL epidemiology is important, since antibiotic resistant strains are of major concern especially, but not only, in hospitals. Recent studies showed that an increasing proportion of ESBL carriers, mostly carrying CTX-M enzymes, is community-associated [2]. Results from a check-up center in Paris, France, showed that the rate of community-associated ESBL carriage increased by a factor of 10 between 2006 and 2011 [3]. Recent data from Bavaria (Germany) demonstrate that 6.3% of healthy volunteers carry ESBL positive Enterobacteriaceae, most frequently CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-1 genes [4]. More and more data suggest that this increase is associated with increasing ESBL rates in livestock, and significant genetic similarities between ESBL isolates in chicken meat and humans could be demonstrated [5]. ESBLs have also recently been described in wildlife animals, with genes which are also found in humans [6].

Usually, ESBLs can easily be identified in the microbiology lab by phenotypic assays based on inhibition of cephalosporin hydrolysis by clavulanic acid [1]. However, co-occurrence of inhibitor resistant betalactamases greatly reduces the accuracy of these assays. This occurs most often when plasmid-encoded ampC beta-lactamase genes are present additionally to the ESBL gene [7]. However, the precise rate of co-occurrence of ESBL and ampC genes is unknown. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are no data derived from lager datasets comparing differences in ESBL genes occurring in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species (spp.) and Enterobacter cloacae. Thus, we examined a large, non-redundant strain collection available at our institute for the occurrence and co-occurrence of the most frequently occurring ESBL and ampC genes.

2. Materials and Methods

Between 2005 and 2009, strains of ESBL positive Enterobactariaceae were collected from routine microbiology samples submitted to the Institut für Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Immunologie und Hygiene of the Technische Universität München. Samples were cultured on blood, chocolate and MacConkey agar plates according to standard microbiology techniques, and clinically relevant strains were identified (Vitek II, Bio-Merieux; or Bruker Biotyper) and their antibiotic susceptibility determined (Vitek II AST-N117 cards), including an automated ESBL confirmatory test. Strains detected as ESBL positive were collected and stored for further analysis.

Before molecular analysis, the ESBL phenotype was first confirmed by E-Test (AB Biodisk) or double disk synergy test using cefotaxim, ceftazidim and cefpodoxim disks with and without clavulanic acid (BD Biosciences) for E. coli and Klebsiella spp., and cefepim disks with and without clavulanic acid (Mast Diagnostica) for E. cloacae isolates, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standard procedures. Confirmed ESBL positive strains were submitted to PCR analysis using the following primers: broad range TEM as described in [8], broad range CTX-M as described in [9], CTX-M subgroups I and II as described in [10], group III as described in [11], and groups IV and V as described in [9]. Primers for plasmidic ampC genes were from [12]. Broad range SHV primers were 5´- TTC GCC TGT GTA TTA TCT CC -´3 and 5´- TCC GCT CTG CTT TGT TAT TC -´3, developed by Y. Pfeifer, Robert Koch Institut in Wernigerode, Germany. PCR products were visualized by agarose gelelectrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining according to standard procedures. Data were collected and analyzed in Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

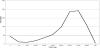

Sources of ESBL positive samples: Between Dec 2005 and Dec 2009, a total of 767 non-redundant strains of Enterobacteriaceae resistant to 3rd generation cephalosporins and ESBL positive by Vitek II analysis were collected at the Institut für Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Immunologie und Hygiene of the Technische Universität München. Two-hundred and forty-four (32%) strains were from intensive care units, 93 (12%) were from outpatient clinics. Most of the isolates were from urine (305 strains, 40%), 268 strains (35%) were from swab cultures, and 125 strains (16%) were from respiratory materials (tracheal secretions, bronchoalveolar lavage, or sputum). Twentyone (2.7%) and eleven (1.4%) strains were from blood cultures or intravascular devices, hence unambiguously indicate invasive infections. Almost half of the strains were detected in 60 to 80 year old patients (378 strains, 49%), but a second peak occurred in infants less than one year of age (45 strains, 5.8%) (Figure 1).

Microbiology of ESBL producers: Among the 767 strains analyzed were 448 E. coli, 245 K. pneumonia, 21 K. oxytoca and 53 E. cloacae strains. Genes for TEM- SHV-, CTX-M or ampC betalactamases could be detected by PCR in all but 9 strains. The mean number of detected beta-Lactamase genes per strain was 2.01. In E. cloacae, a mean of 3.25 beta-Lactamase genes could be detected per strain (range, 1 to 6), followed by K. pneumoniae (mean, 2.29, range 0-4), K. oxytoca (mean 1.86, range 1-4) and E. coli (mean 1.71, range 0-5) (Figure 2A).

Occurrence of TEM-, SHV-, CTX-M, and ampC beta-lactamases: The most frequent beta-Lactamase group was CTX-M, with a total of 645 strains positive. This was followed by SHV (418 strains) and TEM(294 strains) beta-lactamases (Figure 2B). Among E. coli, E. cloacae and K. oxytoca strains, the most frequent type was CTX-M with 87%, 83% and 100% of strains positive, respectively. By contrast, in K. pneumoniae strains, SHV genes were more frequent than CTX-M genes (95% vs. 78% of strains respectively). In E. cloacae, SHV and CTX-M genes occurred with similar frequency. Only 36% of E. coli strains carried a TEM gene.

A total of 80 strains were positive for ampC genes (Figure 2B), all but one E. coli strains with a single gene. EBC was the most frequent one, being the sole ampC gene detected in E. cloacae and K. oxytoca strains. In E. cloacae, EBC occurred almost as often as SHV or CTX-M. Detection of ampC in E. coli and K. pneumonia was more diverse with DHA, EBC, FOX and CIT genes detected.

Figure 2C shows a detailed analysis of which genes occurred together in individual strains. In E. coli, most strains harbored only CTX-M gene(s), followed by co-occurrence of CTX-M with TEM and of CTX-M with SHV genes. By contrast, the combination of TEM with SHV and CTX-M genes was the most frequent genotype in K. pneumonia strains, followed by SHV and CTX-M genes occurring together. Still differently, in E. cloacae, the combination of SHV with CTX-M and ampC was most frequent. Importantly, only two strains harbored ampC genes without concurrent TEM-, SHV-, or CTX-M genes, indicating that false positive phenotypic ESBL tests by VITEK II analysis mediated by ampC genes are rare.

Occurrence of CTX-M subgroups: The most frequently detected CTX-M subgroup was CTX-M-I in E. coli, K. pneumonia and K. oxytoca (Figure 3A). However, in E. cloacae, CTX-M-II and CTX-M-IV genes were more frequent, these groups also were the second and third most frequent group in E. coli (Figure 3A). Thus, the repertoire of CTX-M genes was much broader in E. coli and E. cloacae than in Klebsiella spp. Only in 28 (4.3%) of all CTX-M positive strains, all CTX-M subgroup PCRs remained negative. Examining which subgroups frequently occur together in individual strains, the combination of CTX-M-II with CTX-M-IV was most frequent in all four species (Figure 3B). However, this combination was followed by CTX-M-I with CTX-M-II and CTX-M-IV in E. coli, by CTX-M-I with CTX-M-V in K. pneumonia, and by CTX-M-II with CTX-M-IV and CTX-M-V in E. cloacae.

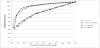

Overall assessment of ESBL genotype diversity E. coli, K. pneumonia, K. oxytoca and E. cloacae: So far, our data indicate that there may be important differences in ESBL genotype between the four bacterial species examined. Figure 4 compares how many different strains contribute to overall genotype diversity in E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and E. cloacae. Interestingly, in E. coli and K. pneumonia, a much smaller proportion of all strains examined accounts for a given extend of genotypic variability than in K. oxytoca and E. cloacae. For example, in E. coli and K. pneumonia, less than 20% of the strains examined cover 80% of the detected genotypes.

By contrast, in K. oxytoca and E. cloacae, approx. 60% of the strains examined are needed to cover for 80% of the genotypes. Thus, regarding overall beta-Lactamase diversity, E. coli and K. pneumonia have fewer, more dominating strains than K. oxytoca and E. cloacae, where the contribution of the most frequent strains to overall number of genotypes is much lower.

Evidence for plasmid transfer between bacterial species in vivo in clinical settings: Our dataset contains 80 patients in which more than to a maximum of three different strains per patient (151 strains in total). We hypothesized that if inter-species plasmid transfer occurred in vivo in these patients, strains from different species should have the same beta-Lactamase genotype, except for beta-Lactamases which may be chromosomally encoded. We thus looked specifically for strains of different species detected in the same patient with identical beta-lactamase genotype, but accepting additional occurrence of potentially chromosomally encoded TEM in E. coli, SHV in Klebsiella spp. and EBC in E. cloacae. In fact, we could identify 23 patients with 47 strains where plasmid transfer from one species to another may have occurred (Table 1). Thus, among patients harboring >1 ESBL positive bacterial species, 71% may have been repeatedly colonized by different strains, while in 29%, plasmid transfer may have occurred after a single colonization event.

4. Discussion

With a total of 767 nonredundant clinical strains analyzed, our study constitutes – to the best of our knowledge - the largest body of information about molecular epidemiology of broad spectrum betalactamases to date. The vast majority of our strains (726 of 767) has been collected between 2007 and 2009 and comprises all different ESBL strains from our institution isolated in this timeframe. Like many other recent studies from Europe, we find a strong dominance of CTX-M enzymes in our dataset (84% of all strains tested were positive for CTX-M genes). Earlier, albeit much smaller, studies from Germany detected CTX-M enzymes in up to 98% of examined strains [13-15]. In 195 hospital-acquired strains of the U.S. SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, only 44% carried CTX-M genes [16]. However, another study detected CTX-M enzymes in 91% of community-acquired E. coli strains in the US [17]. Whether this constitutes a real difference, sampling bias, or changes in molecular epidemiology over time remains to be determined: In suburban New York, the prevalence of CTX-M positive Klebsiella pneumonia isolates strongly increased in recent years, while the increase in CTX-M bearing E. coli was much less pronounced [18]. Similarly, an increase in CTX-M-bearing E. coli and Klebsiella spp. was described in Texas between 2000 and 2006 [11]. By 2012, CTX-M group I became the most prevalent group of ESBL throughout the United States, with 43% of 701 strains collected [19]. Recent data from Canadian hospitals show a similar dominance of CTX-M enzymes, particularly CTX-M15, as in Germany [20]. Thus, we conclude that our data are in accordance with the global spread of CTX-M enzymes currently described in several regions worldwide.

In the German studies, CTX-M15 was the most frequently isolated gene [13-15]; as this belongs to the CTX-M-I group, this is also in concordance with our data. It should be noted, however, that the predominance of certain CTX-M alleles shows substantial geographic variation: in Spain, the most common CTX-M allele is CTX-M14 [21,22]. In the US SENTRY dataset, CTX-M15 is the most frequently isolated CTX-M gene [16], as it is in Canada [16]. However, we would like to point out that the distribution of CTX-M alleles is different in different bacterial species: While the CTX-M-I group is the predominant group in E. coli and Klebsiella spp., this is not the case in E. cloacae, where subgroups CTX-MII and CTX-M-IV dominate. The reasons for this difference are currently unclear, since E. cloacae is only infrequently examined for ESBL production and molecular studies are rare. Qureshi et al reported that among 31 isolates from blood stream infections, 29 harbored an SHV-like ESBL, while only two strains carried a CTX-M enzyme [23]. While we also find a high proportion of our E. cloacae strains to carry SHV genes, most of them also have CTX-M genes. In Brazil, more than 50% of ESBL positive E. cloacae strains have been shown to carry CTX-M15, a result quite different from ours [24]. In China, most E. cloacae strains resistant to carbapenems have been shown to co-express TEM and CTX-M ESBLs, with a smaller proportion being positive for SHV enzymes [25]. Thus, in line with our data, the molecular epidemiology of ESBL producing E. cloacae may be more diverse worldwide than that of other Enterobacteriaceae.

We can confirm earlier data that most of the ESBL positive strains carry more than one beta-lactamase gene. In the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, two to nine beta-lactamase genes were detected in individual strains [16]. In the US 2012 strain collection [19], 63% of the isolates carried more than one ESBL gene. Similarly, the Canadian CANWARD surveillance reported multiple beta-Lactamase production in 74% and 83% of ESBL-positive E. coli and Klebsiella spp., with a maximum of 4 genes detected [20].

The detection of chromosomally encoded EBC and SHV genes in E. cloacae and Klebsiella spp., respectively, indicates that the chosen PCR strategy works well. However, since we did not sequence individual amplicons, we were not able to differentiate non-ESBL from ESBL enzymes in strains positive for TEM- or SHV genes.

While the molecular epidemiology of ESBL genes has been extensively characterized, much less is known about co-occurrence with ampC genes. We found 80 strains positive for ampC genes, constituting approx. 10% of all strains analyzed. Remarkably similar numbers are reported from the SENTRY surveillance program (11%) [20], from an international strain collection acquired during the tigecycline phase 3 trials (8,5%) [8], and from the US 2012 strain collection [19]. However, another study from Singapore reported only one isolate among 54 tested co-expressing ESBL and ampC genes [26]. One limitation of our study is that our strain collection is biased against ampC producers: We only analyzed strains which were positive for ESBL confirmatory tests, and strains concurrently producing an ampC enzyme could be expected to be negative in the phenotypic ESBL confirmatory tests. However, only very few strains were cefotaxim resistant and negative in ESBL confirmatory tests (data not shown), so this should not significantly affect our results and precludes inclusion of these strains as a control group. It would, however, be possible to extend on our observations by analyzing with PCR all cefotaxim resistant isolates irrespective from the result of the ESBL confirmatory tests. While the possibility of horizontal gene transfer in vivo in patients seems obvious, only very limited data are available. Fernandez et al. [27] report a patient with recurrent urinary tract infections being colonized by E. coli and Proteus mirabilis harboring the same CTX-M-32 bearing plasmid, demonstrating that horizontal gene transfer may indeed be possible in vivo. Similarly, Göttig et al report the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer of an OXA-48 bearing plasmid from K. pneumonia to E. coli during a nosocomial outbreak in 1 of 6 patients [28]. More importantly, Doi et al. [29] try to quantify the extent of horizontal gene transfer and cross transmission, respectively, in long-term care facility patients. They found 6 occurrences of horizontal gene transfer events in 25 patients colonized with SHV-5 or SHV-12 bearing E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains (24%). This figure is quite similar to our analysis, where we found evidence of horizontal gene transfer in 29% of patients. We conclude that plasmid transfer in vivo in individual patients is not a rare, but rather a common, event.

According to our data, the molecular epidemiology of ESBL and ampC enzymes is complex. In our collection of 767 bacterial strains, we could detect 73 different genotypes. Castanheira et al reported 55 different gene combinations among 157 isolates [16]. Jones reported 50 genotypes from 272 isolates [8]. Thus, if a sufficiently large strain collection is analyzed, molecular epidemiology of ESBLs is as complex in a single institution as it is in national or even international strain collections.

5. Conclusion

Molecular epidemiology of beta-lactamase genes in enterobacterial strains positive in phenotypic ESBL assays is as complex in a single institution as it is on a national or international level. As in other parts of Europe, CTX-M enzymes dominate in our study. Co-occurrence of ESBL and plasmid-encoded ampC enzymes in species without chromosomally encoded ampC seems to be a rare event. By contrast, co-occurrence of different genes potentially encoding ESBL enzymes is frequent. Transfer of resistance plasmids between bacterial species seems to occur in a certain percentage of patients in vivo.

Author Contributions

Thomas Miethke and Reinhard Hoffmann designed the study. Charlotte Bogner performed the experiments- Reinhard Hoffmann analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Nina Wantia, Friedemann Gebhard and Dirk Busch were involved in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Yvonne Pfeiffer, Robert-Koch-Institute, for provision of broad range SHV primer sequences.