1. Introduction

The health of working populations is of growing interest to all countries in the developed world [1] . Furthermore, governments are increasingly committed to improving the health of working population in order to reduce the amount of claims for sickness and disability benefits [2-4]. In the majority of European countries the level of reported sickness absence is often used as a proxy measure of disease burden [5-7]. In recent times Ireland has become more aware of the importance of sickness absence data and has implemented initiatives such as the Fit for Work strategy to combat and improve the return to work process. Fit for Work Ireland, through their work with key stakeholders from both the work and health arenas, have produced guidelines to help manage and support those working with musculoskeletal disorders in the Irish workplace [8] .

Currently, the total cost of sickness absence in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) is not widely reported. Although, it is estimated that work related absence costs the small business sector over 490 million euro per year [9] . While the costs of sickness absence in monetary terms are significant, the indirect costs of ‘worklessness’ are thought to be much higher and include, poverty, social isolation, increased risk of suicide and greater utilisation of health services, including primary care [10,11]. In many countries the role of the General Practitioner (GP) to act as ‘gatekeeper’ in sickness leave, underscores three main objectives; a need to legitimise the illness, the need to ensure adequate treatment and rehabilitation for the patient and lastly to control the distribution of benefits [12] . In the ROI, GPs are responsible for issuing of sickness certificates, firstly to show that the person’s reason for workplace absence is illness related and secondly to enable claims for illness related benefits. Illness benefit (IB) may be claimed from the Department of Social Protection (DSP) if a person is unable to work due to illness for a period of up to 2 years. The requirements for IB is that the patient is under 66 years and satisfies the pay related social insurance (PRSI) conditions [13] . Claims must be made within 7 days of becoming ill. Payment is then made after a waiting period of 6 days. (Note that this was extended from 3 to 6 days from 6 January 2014). The majority of the Irish workforces are deemed eligible for IB in that they earn greater than €38 per week. However, self-employed persons are not eligible for IB. Occupational Injuries Benefit (OIB) is a related benefit payed to people injured or incapacitated by an accident at work or while travelling directly to or from work. The scheme also covers people who have contracted a disease as a result of the type of work they do. In the case of both IB and OIB, GPs are required to indicate the reason for absence, however some evidence suggests that GPs remain unware of the levels of sickness absence in the working population and are therefore unable to respond appropriately or influence policy. The current system is not coded directly under the International Classification of Disease (ICD), although some broad categories are used in current reporting.

The aim of this paper was to examine sickness absence trends in the ROI as reported by medical certification on the claiming of IB over a seven year period, namely 2008 to 2014. The main outcome measure was to identify the most frequent causes of illness resulting in absence from work using the ICD-10 criteria. A secondary objective was to examine the most frequent causes of occupational related illness resulting in sickness absence in the Irish workplace.

2. Materials and Method

2.1

The study population included all persons that made a claim for illness related benefits during specified years 2008 and 2014 inclusive. For this study the data were extracted by the Statistical unit of the DSP from their central database to include all claims for illness and occupational injury benefit between 2008 and 2014. The GP must issue and sign the medical certificate (MC1) and the patient is required to complete personal details including public service numbers, gender, age, marital status and income levels to claim benefits. Occupational illness data must include additional information detailing the accident or injury incurred and this must be witnessed and co-signed by the employer. This data is then entered for the processing of illness benefit payments and is electronically recorded at the DSP.

2.2 Data analysis

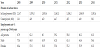

This data was presented to the researcher as an Excel® file following a data request under the freedom of information act 2014. The data included all claims awarded and in payment at each individual year end grouped by 227 illness categories. Information on the demographics of claimants (gender and age) was also provided along with information on total expenditure. Data were examined and recoded by the researcher using broad codes contained in the ICD- 10. For example, if back pain was indicated as the cause of absence on the medical certificate then this was reclassified under disease of the musculoskeletal system (M00-M99). When all coding was completed 10% of the coded data was rechecked to ensure accuracy. A random numbers list was generated (based on the 227 categories) and 23 records were extracted for each year and checked against the ICD code assigned. No errors in coding were found. Data were then combined into a database and summative values were produced under each classification. To evaluate the average rate of claims (i.e period prevalence) [14] , the total employed workforce for each independent year was used as a denominator (obtained from the Central Statistics Office (CSO) (Table 1). This produced a rate of claims per 1000 persons employed per year. Data was tabulated to illustrate trends in benefit claims for illness over time. Due to the low number of occupational related reported cases, the data were prepared to illustrate the highest reported conditions under the ICD-10. The data was displayed graphically to show trends in OIB claims over time (2008-2014). Claims that could not be classified under the ICD-10, (for example surgery/incapacity/illegible) were reclassified as other.

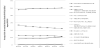

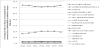

The two main categories accounting for the highest proportion of illness benefit claims were subdivided into specific illness type and examined across the seven year period. The illness type was then calculated as a proportion of those presenting and being certified with the condition for each independent year.

3. Results

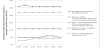

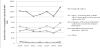

A total of 67,021 illness benefit claims were made in 2014 and this compared to 73,609 in 2008. When the total workforce is considered this represents a total reduction from 34.2 claims per 1000 person employed (2008) to 30 claims per 1000 employed (2014). Figure 1 illustrates the top five illness reported as a percentage of the total number of claims from 2008-2014. Table 2 illustrates the rate of illnesses benefit claims per 1000 persons employed per year. Mental and behavioural disorders (FF00-F99) had the highest rate of illness benefit claims year on year. Overall a slight decrease of 6.8% was observed from 2008 (8.8 claims per 1000 persons employed) to 2014 (8.2 claims per 1000 persons employed). When further analysed, anxiety and depression accounted for 49.5% of claims and stress accounted for 24.2% over the seven year period. Figure 2 shows trends in claims under each specific category of illness F00-F99 from 2008 - 2014. Disease of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99) had the second highest rate of claims. Similarly, a decrease was observed in claims over the seven year period from 7.6 per 1000 person employed to 6.6 per 1000 person employed. Figure 3 illustrates the most likely reason for certification under the ICD-code M00-M99 (2008-2014). Back/neck/rib and disc problems accounted for 62.7% of all illness benefit claims when combined over the 7 year period. This was followed by arthritic conditions (rheumatism and osteoarthritic (OA)) at 19.5%. Medical certificates that could not be classified under ICD-10 accounted for 12.5% of the total claims for IB. This figure was consistent across each year from 2008-2014.

The total number of claims for occupational injury was similar across the seven year period. The principal reasons for occupational injury claims were for injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external cause (S00-T98) followed by diseases of the musculoskeletal and connective tissue (M00-M99). Both conditions account for over 85% of the total claims for OIB. Figure 4 shows the trends in claimsover 2008-2014. On further examination of the data, breaks, fractures and injuries to the lower extremities (leg, ankle and knee) were the most likely cause of OIB claims and accounted for 60% of the total claims under the category S00-T98. Claims for back, neck, rib and disc (74%) were most likely under the classification for musculoskeletal and connective tissue (M00-M99). Occupational stress accounted for just 23 claims in 2008 and 38 in 2014.

4. Discussion

In this research, the rate of claims for IB was examined in each yearly period over a seven year time frame. The data presented shows that the most frequent cause of work related absence as reported by GPs under the IB scheme is mental and behaviour disorders followed by diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue. The high level of sickness certification for both musculoskeletal and mental health related problems present a worrying trend for GPs, employers, benefit agencies and public health. Emerging evidence from other countries is that conditions such as musculoskeletal and mental health related problems pose particular difficulties for certifying GPs due to limited measurable pathology [15,16]. Research suggests that GPs must often rely on the patient’s own assessment of functional capacity to work [17,18]. Indeed, concerns have been raised in relation to the skills of doctors in managing fitness for work, their knowledge of a patient's working tasks [19] . Recent research conducted with GPs workings in the ROI also supports these findings [20,21]. The benefits of work are widely recognised and in particular for those with mental health related conditions. In recent times efforts have been made across Europe to improve the reporting of illness to employers so that reasonable adjustment can be made to facilitate employees to remain in the workplace. For example, in the United Kingdom (UK)the ‘Fit note’ has been recently introduced and is aimed as stating what the employee can do rather than what they are unable to do [22] . In a recent study of 198 Irish GPs, 53% indicated preference for the introduction of a fit note and cited lack of rehabilitation service as one of the main factors impacting on patients return to work [23] .

Although there appears to be a decreasing trend in overall individual claimants over the period, this is most likely as a result of changes in the recent waiting period of 3 to 6 days for claiming illness benefit and the current economic conditions [13,24]. At present, there appears to be no clear role within the Department of Health in the ROI in use of sickness certification data in determining healthcare utilisation resourcing and planning. This presents a void. One recommendation following the evaluation of this data is that current disease reporting contained within the medical certificate could be easily adjusted to follow the ICD codes and used as a comparative measure both nationally and internationally [25] . This disease reporting could be used to inform policy on work practices identifying the most at risk groups and prevention activities and equally the allocation of resources to help GPs in practice with managing fitness for work matters. The co-signing of a medical certificate for OIB is also likely to act as a deterrent for some employers due to fear of litigation [20,26]. Figures from the Occupational reporting network (THOR-GP) in the UK suggest much higher incidences of work related mental ill health in comparison to those seen in the Irish workforce [27] . It is likely that work is a contributory factor in many illness benefit claims and failure to recognise or acknowledge the impact of work on development of certain disease may limit preventative measures.

There are a number of limitations in respect to this data. Not all people are eligible to claim illness or occupational injury benefit and exclude those working in self-employment. Distinction cannot be made between self-employment and employed persons in the calculation of the total workforce figures which leads to some inaccuracies in the data. Some illnesses were recorded as surgery/ incapacity/illegible and therefore could not be coded under the ICD- 10. Data excludes all short term illness that is illness of duration of less than three days between 2008-2104 and six days 2014. This data set cannot be fully scrutinised by gender, age and occupation and although this information is gathered by the DSP it is not available in a suitable format (anonymised individual records) for subgroupanalysis.

5. Conclusion

Despite the limitation outlined this study provides valuable and useful information for the healthcare system and for policy makers and shows that data collected from illness benefit claims is useful. Results of this study should be taken into account for future planning of primary healthcare in the Republic of Ireland and for training of GPs in practice. The majority of claims for illness benefits are associated with diseases of the musculoskeletal system and mental health conditions and are comparable with trends in other industrialised countries. However, additional resources to help facilitate the return to work process could include physiotherapy, counselling services and occupational health support [23] . The introduction of a certification system that allows for adapted work practices such as reduced work hours or alternative duties may help GPs and employers to facilitate early return to work or allow the person to remain within the workplace during their spell of illness. Similar practices have been introduced in the UK through the ‘fit note’ initiative and this now needs to be given full considered in Ireland. While the role of GPs in acting as gatekeepers for the DSP may have practicalities in a broader sense it may not be sufficient in the requirement to act as an ‘expert’ in assessment of fitness for work. The debate needs to focus on role of GPs in the delivery of workplace health and how this role can be adapted in the future to improve the health of the working population.

Competing Interests

The author declare that there is no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.

Abbreviations

ROI: Republic of Ireland; GP: General Practitioner; DSP: Department of Social Protection; ICD: International classification of diseases: IB: Illness Benefit; OIB: Occupational Injury Benefit