1. Introduction

Social networking sites have become one of the most popular destinations online, and are ranked among the top ten most visited sites in the world [1]. As the popularity of social media continues to grow, it has also raised some interesting questions regarding their impact on democratic citizenry. Recent cases illustrate that during times of political upheaval, social networking sites functioned as an effective tool for citizen communication, to the extent that their use increased the odds of citizens’ participation in protests [2]. While these and other research efforts have highlighted the significant potential of social media as a new venue for political communication, the nature of political discourse in online social networks still remains to be explored.

The fundamental question motivating this research is whether the newly emerged social media platforms can create an egalitarian public sphere that is fundamentally open and embodies a decentralized structure of participation [3]. In exploring this question, this study tests whether the rise of social media prompt a departure from the traditional two-step flow, in which the opinion-leader would moderate the flow of information in social networks. With a large dataset of Twitter, the current study examines the structure of information sharing to understand how users with different levels of influence shape the flow of information in online social networks. In addition, by exploring the participants in conversations over an extended period of time on Twitter, this study sheds light on the concentration of political discourse among users in social media.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Political communication in social networks

Research suggests that all interpersonal relations and constructions of a citizen’s social network serve as a filter on the macro environmental flow of political information [4]. The consequences of the larger information environment often depend on the existence of micro-environments and social networks which expose citizens to surrounding opinion distributions. The flow of information in social networks is thus understood as a process of individual preference operating within larger contexts of the information flow [4]. This networked flow of ideas and information is present in social media more than anywhere else, where individuals obtain information while building interpersonal connections. It is neither the individual preference nor the information environment itself that solely determinate the flow, and thus the information that citizens ultimately obtain through social channels of communication can be considered as contingent on the particular intersection between the individual and the environment.

Studies have illustrated the importance of the socially influential individuals in shaping informing fellow citizens, public preferences, and altering political behavior [5-8]. This line of research identified that certain individuals tend to pay more attention to issues, frequently discuss them, and consider themselves as persuasive in convincing others to adopt an opinion or course of action [9]. In the “two-step flow of information,” certain individuals act as social intermediaries of mass-mediated communication, and the ideas flow from the mass media to opinion leaders and from them to the less active section of the population [9]. Opinion leaders in this context do not necessarily hold formal positions of power or prestige in communities, but rather serve as the connective communication tissue that alert their peers to what mattered among political events, social issues, and consumer choices [9]. Katz and Lazarsfeld [9] also state that opinion leaders are not a distinct group set apart, and opinion leadership does not necessarily seem to be a trait that some people have and others do not, but rather is an integral part of the everyday personal relationships. According to their research, opinion leaders are distributed in all occupational groups, and on every social and economic level, and their opinion leadership is almost invisible and is certainly an inconspicuous form of leadership at the person-to-person level of ordinary, intimate, informal, everyday contact [9].

While the importance of opinion leaders has been addressed in various contexts such as product consumption and diffusion of technology, opinion leaders are generally regarded to have a considerable sway over fellow citizens’ reactions to political issues and public agendas [10,11]. They have been found to actively participate in political discussions, speak at public meetings and come into contact with many people through active engagement in voluntary social activities [8]. In addition, Katz [9] argues that opinion leaders tend to be active news consumers and expose themselves considerably more to political information through various outlets of the mass media. The influential status granted by the opinion leadership is likely to encourage them to seek news in the media [10], which in turn can promote participation in political activities [11].

In line with this view, the growth of the Internet as a mass medium further widens the range of media options an opinion leader can explore and provides opinion leaders with a new tool in their efforts to learn about issues of interest [14]. The Internet enables opinion leaders to seek information with personally pertinent details about issues and ideas encountered in other contexts, permitting them to collect information to enhance their potential influence [14].

On the other hand, the open nature of social networking sites raises the possibility that new forms of information structures might become manifest, and herald a departure from the two-step flow of information. That is, in the absence of a moderating mechanism between mass mediated content and the public as theorized in the traditional two-step flow model, the new social media environment might present users with an open and egalitarian sphere to freely access and disseminate information, regardless of their influential status. Thus, this research explores the information flow in social networks to shed light on the usage patterns of individuals with different levels of influence.

2.2 Social Media as a Venue for Political Discourse

One of the major current debates in the field revolves around whether the new media environment redefines the sphere for political discourse. Researchers suggest that the interactive context on the Internet can invigorate political discourse, due to the absence of nonverbal cues [15,16], and exposure to opinions beyond the confines of participants’ immediate associations [17]. Nevertheless, studies have shown conflicting results regarding the actual presence of a participatory and egalitarian public sphere on the Internet [18], with evidence suggesting that political discussions tend to be restricted to only a few participants.

The recent developments in communication technology, particularly the rapidly diffusing social media platforms, have drawn scholarly interest in complementing person-to-person social interaction and redefining the diffusion of information [19]. Social networking technology not only facilitates interaction among individuals but also gives each individual an opportunity to voice their opinions. While the opportunities to reach an audience were limited to large media corporations in the traditional media environment, the new social media platforms have created a public sphere where virtually everyone can be participate and exert influence on the flow of information. This open nature of social networking sites provides an interesting context to revisit the question of the realization of an egalitarian public sphere, as well as the definition of influence.

Social networking technologies have enabled all users express their viewpoints, yet the extent to which each voice gets heard still seems to differ enormously depending on their influence exerted in networks. As a matter of fact, when there are few barriers for citizens to express their views online, “what matters is not who posts but who gets read” [20]. In other words, the notion of influence in social media context should not be equated with the tendency to be expressive on social and political issues but rather conceived in terms of who gets heard, by incorporating followership to the measure of influence.

2.3 Defining influence in social media

Previous research has put forth different ways of measuring personal influence in the context of social interactions. For instance, the socio-metric method asks all members of a community to report about to whom they go for advice and information about an idea. This method requires a full report of the whole network, and is less suitable for sample designs. On the other hand, the self-designating method would ask the respondent to report on the degree to which they perceive themselves to be an opinion leader. This accuracy of this method would depend heavily upon the respondents’ self-images, and therefore the validity of the measure would remain questionable. While the two ways of measuring influence provide insight into the respondents’ perceptions of influence, both are subjective. Thus, a more objective way of measuring influence was proposed, in which the researcher identifies and records all of the flow of information.

The social media environment provides a new environment to study influence. The availability of large data sets that document the number of individuals following others, as well as the number of times a piece of information has been shared with others, create an opportunity for research to unobtrusively measure the reach and impact of individuals. As a beginning step, this study operationalizes influence in the Twitter context, and explores the following research questions.

RQ1: Do users with different levels of influence in social media exhibit different patterns of information sharing?

RQ2: Do social media facilitate equal participation in political conversations?

2.4 Twitter

This study examined political conversations in Twitter, one of the most popular social networking platforms. The following section introduces Twitter as a social media platform to establish a common ground of understanding about its core practices, as well as the unique features that make Twitter a particularly applicable subject for this study. Launched in summer of 2006, Twitter allows users to send status updates with their social network. Users are constrained to expressing themselves in tweets of 140 characters or less. In addition to their own profile page, each user can view status updates of others they follow in an aggregated timeline. With over 500 million registered users and approximately 400 million tweets per day, Twitter not only reveals the growing prominence of social media as a sphere for public discourse, but also the unprecedented efficiency with information is disseminated through online networks of individuals. While some consider the social media platforms to be primarily dedicated to recreational purposes, reports indicate that aside from self-promotions and “pointless babble”, 4% of tweets are news.

As in other similar types of social media platforms, Twitter users are connected through an underlying network structure, but their connections are directed rather than undirected, which means that the relationships on Twitter are not based on reciprocity [21]. Twitter users can follow others and see their tweets, but the other user need not reciprocate [21]. Being a Twitter follower means that the user will receive all tweets from other users that he/she follows.

A tweet refers to a statement made by a Twitter user that is broadcasted to the users’ followers, who subscribe to the information shared by the user. Tweets can be categorized largely into two types: an original tweet and a retweet. In addition to sharing simple status updates, a Twitter user can re-broadcast a tweet to its own followers by re-tweeting or replying to the tweet. Retweeting is a common practice in Twitter to copy someone else’s tweet, allowing individuals to rebroadcast content generated by others, raising the visibility of the information shared [22]. Retweeting is considered the feature that has made Twitter a new medium of information dissemination.

As participants embraced the technology and its affordances, a series of conversational patterns emerged that allowed users to add structure to tweets. An individual might decide to post a message, picture, or link to an article, addressed to a specific individual (@) or no one in particular, about a specific subject. Users can also share links to other outside sources (URLs), reference other users in their own tweets (mentions), and attach labels to indicate topics (hashtags #). One of the central usage pattern emerged in Twitter is to share links to outside content by including the URL in their tweets. Due to the 140 character limit in tweets, shorteners of URLs (e.g. http://bit.ly) have been devised to generate abbreviated URLs that redirect to the desired website. Twitter users also address specific users directly by mentioning other users in their tweets (@mention). This convention functions to direct tweets to reply to specific people, as well as to obliquely reference another user [21]. This type of addressing specific recipients in public forums is an intended act of targeting the persons’ attention, which is essential for conversations to occur [23]. The use of hashtags (#) to annotate the tweets with keywords that specify the topic or intended audience is another remarkable feature of Twitter use. The practice of annotating tweets with keywords parallels the use of “tags” to freely categorize content on the web [21]. Tagging has gained visibility with social bookmarking on the web, and expanded to blogs and other social media platforms [21].

Retweeting, in particular, can be understood as an effective method of diffusing information. Spreading tweets is not simply to get messages out to new audiences, but also to validate and engage with others [21]. Some users add additional comments when they retweet or share links, as a form of commentary to news or information. Retweets can also be understood as an act of endorsement, as the Associated Press guidelines on employee’s use of social media are: “a retweet with no comment of your own can easily be seen as a sign of approval of what you are relaying”.

3. Methods

3.1 Data

The dataset is a random sample of about 25,000 tweets on the topic “abortion” from the public Twitter timeline in the first half of the year 2013 (January 1 to June 30). To access the archive of tweets, Sysomos, a commercial vendor with the fire hose access to the full archive of Twitter was used. This sample includes 24,987 unique tweets, but does not include tweets from those with protected accounts. For each user of Twitter in the data set, the number of followers and following, along with the content and time-stamp of all posts were obtained. This data set consisted of a total of 309,740 users, with an average of 255 posts per user, with 85 followers, and following 80 other users.

Abortion represents an issue of ongoing political debate in the United States. While some issues receive relatively fleeting attention in political conversation, others including abortion develop a sustained and seemingly permanent place on the political agenda [18]. Though abortion had peaks and valleys in terms of the relative amount of attention devoted to it, the issue remains at the forefront of public discourse. Drawing from the case study on discussions on abortion in the context of Usenet groups in the early days of the Internet [18], this study revisits conversations on abortion in the social media context, and examines the flow of information [24,25]. The tweets on abortion in this dataset were collected through the use of Boolean searches of tweets that included key phrases such as abortion, and variations of pro-choice and pro-life (e.g. abortion, abortion AND pro-choice, abortion AND pro-life, etc.).

4. Results

The central motivation for this study was to understand the meaning of social media as an online public sphere for political discourse. With analyses of Twitter data on the subject of abortion, this study first examined the characteristics of users who participated in public discourse, and the extent to which social media platforms served as an open sphere for all users to voice their opinions. Results in Table 1 provide insight into the distribution of users who participate in political discourse, with respect to their influence in the network. Instead of relying on raw number of followers or follows, this study captures the fundamental principle of social influence, through the use of reciprocated and unreciprocated relationships manifest in Twitter. That is, the ratio of followers to following characterizes how an individual user can potentially exert influence in online social networks. When an individual is following many but is not followed by others, information shared by this user is less likely to be disseminated to a large number of people. On the other hand, when a user is following only a few others, but is followed by many, we can expect that information shared by this user is likely to reach a wider audience.

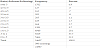

As shown in Table 1, the number of followers per user ranged from 0 to 2,842,549. That is, some users had no followers while others had up to over 2 million followers. The ratio between followers and following ranged from 0 to 311,116. The mean value of this ratio was 33.8, while the mode was .5 in the sample. These descriptive statistics illustrate that while some users appear to have a large crowd of followers or audiences, most Twitter users tend to follow others at least 2 times more than the number of users who follow them. The proportion of users with a follower:following ratio of less than 1 was about 60% of the sample. Meaning that the majority of users were following more people than they were being followed. On the other hand, about 7% of users had a ratio over 5. Given the nature of the topic, this random sample of users did not include celebrities that are known to have a greater number of followers, which shows that some individuals tend to have greater presence in discussions on even on political topics.

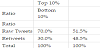

Table 2 presents results of analyses that address the questions raised in RQ1, which asked whether influential and ordinary users of social media exhibit different patterns of information sharing. As shown in Table 2, the tweets of the top 10% of influential Twitter users were more likely to be direct tweets (70%) than retweeets of someone else’s tweet (30%). In contrast, the bottom 10% of Tweeters showed a comparable rate of direct tweets (52.5%) and retweets (48.5%). Influential (top 10%) and ordinary (bottom 10%) users did not show significant differences in the rate of links shared in their tweets.

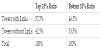

To revisit the two-step flow of information in the Twitter network, this study focused on whether influential and ordinary users differ in role as intermediaries of information into their network. By focusing on the links shared in tweets, this study compares the rate of original links shared with retweets of links that have been introduced by other users. While original tweets can be conceptualized as introducing novel information, retweeted links can be seen as re-circulating information that have been introduced by others. A comparison of the top 10% of users with the bottom 10% users provides a look into their different practices of Twitter use.

While Table 3 shows that there is no significant difference among the top 10% and bottom 10% of users in the proportion of sharing links, the results in Table 4 provides an contrast about the nature of links shared. As shown in Table 4, the top 10% of influential Twitter users were more likely to share links that have not been shared by others, with 73% of the links shared had the user to be the original sharer of the link. Only around 26% of the links shared by the top 10% influential were previously introduced by other intermediaries of the information. On the other hand, the bottom 10% users exhibited the exact opposite pattern with the majority of links they shared were retweets by other users (65%).

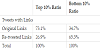

RQ 2 asked whether social media could facilitate participation public discourse to produce a more open sphere of political discourse. To address this question, the current study explored the extent to which participation in the discourse on abortion in social media reflect the dimension of equality. Toward this end, this study began by examining the dimension of equality of participation in public discourse on social media platforms. Equality of participation was measured with the frequency of a users’ expression in the entire discussion on abortion. As shown in Figure 1, the extent to which the top 100 ranked users tweet on the topic of abortion was more than 600 times more than the average user, who had only 1 tweet during the entire period of time. Figure 1 summarizes the concentration of conversation in Twitter. The horizontal axis in Figure 1 ranks participants from the most participatory to the least participatory, with the number of tweets they contributed on the subject of abortion. As is evident from Figure 1, posting behavior tends to be concentrated, with very few authors contributing more than 1 tweet during the entire time period. The number of tweets each user contributed on the subject of abortion ranged from 1 to 634, with only 24% of users contributing more than 1 tweet. In other words, 86% of the users in the sample contributed 1 tweet on the topic of abortion.

5. Discussion

The results of this study provide valuable insight into the potential of social media as a sphere for democratic discourse. First, the results of this study suggest that while the social media platforms appear to provide an optimal environment for egalitarian political discourse at first glance, in reality, there seems to be a concentration of participation in conversations. While this finding does not undermine the potential of social media to function as a venue for news and political talk, it raises concerns regarding the way in which the political consequences of social media use are generalized to the public. Although individuals might have embraced social media as a venue for political conversations, the intensity with which issues are being discussed varies significantly between users.

In addition, a notable difference in the usage patterns among Twitter users emerged in shaping the flow of public discourse. Rather than re-disseminating information shared by others, individual users who had a larger crowd following them were more likely to share original tweets. While there was no significant difference found in the proportion of tweets containing links, a closer look into the nature of links illustrated an interesting difference. Users with the top 10% ratio of follwers: following were more likely to share original links than to share links that had already been tweeted by others. In contrast, those with the bottom 10% of the ratio were more likely to re-tweet links that had been already shared, rather than sharing original content. These findings suggest that while social media platforms allow all users to disseminate information, the nature of the information shared by those deemed influential are different.

Second, the analyses presented in this article preliminary evidence to suggest that the political conversations in online social networks tend to be concentrated among a few participants, which raises questions regarding their potential as an egalitarian sphere for political discourse. While social media are fundamentally open to anyone and there is no structural filter that functions to moderate the flow of information, the concentration of political discourse and the different patterns of information dissemination might preclude the participation of the majority of users.

There are a few limitations of this study that warrant discussion. First, while the random sample of Twitter data provides an interesting step toward understanding its role as a public sphere, it only provides a partial view of the political discourse in social media. Social networking sites operate on different platforms with different algorithms, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the 140-character limit can raise questions regarding its effectiveness as a sphere for political discourse. In-depth analyses of the conversation threads can provide a more refined understanding of the nature of social media as a public sphere. While this study focused on numerical operationalization of influence in social networks, future research would benefit from a more qualitative definition of influence, and to examine the relationship between users’ influence and their dominance in political conversations.

Competing Interests

The author declare that there is no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.