1. Introduction

The average rate of Caesarean section is slowly increasing in Benin, but with disparities by socio-economic factors particularly between urban and rural areas and by wealth quintiles. The Lagune Mother- Child University Hospital (HOMEL) in Cotonou, the largest in the country, is an illustration with a Caesarean section rate of 38.53% in 2009 vs approximately 15% at national level. In spite of, and because of its status as a reference hospital, this rate is very high. Cesarean section, initially conducted as last resort has become a security practice. The uterus scar is a major prophylactic Cesarean indications. Yet the uterine test has been widely studied in developed countries and its benefits are universally recognized. Given the differences in context and particularly the limited working conditions in developing countries the results in developed countries are not transferable to developing countries. The need to reduce the cesarean rate without harming the mother, the fetus and the newborn is fairly recent in Benin. Obstetricians would accept the indication of uterine test only in case of spontaneous onset of labor. At the Lagune Mother-Child University Hospital in Cotonou, active onset of labor was adopted. The main risk of this choice is uterine rupture which ranges from 0.77 to 4% across studies [1] . To reduce the risk of maternal complications, fetal and neonatal that would be increased by cervical ripening [2] , it was established at the Lagune Mother and Child University Hospital, a score of the use of oxytocin on uterine scar. The monitoring of this score would assist with careful review of the case and decision or not for cesarean section. The objective of the study was to determine the outcomes of labour induction on scarred uterus and establish the maternal and perinatal prognosis in a country with limited resources.

2. Patients and Methods

The study was conducted at the Lagune Mother and Child University Hospital (HOMEL) in Cotonou, Benin which is the largest maternity hospital in the countries in terms of admissions, cases load, and human resources. This was a cross sectional, prospective study that covered a 5 years period from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2013. The sampling frame was pregnant women admitted to Lagune Mother and Child University Hospital for delivery. Inclusion criteria were: established pregnancy, scarred uterus (whether single scar; crosssegmental hysterotomy scar; clinically normal pelvis, fetus in vertex presentation; placenta normally implanted; a favorable oxytocin infusion Bishop score (which means ≥7). This score took into account: maternal age; parity; the order of Caesarean section compared to other vaginal deliveries; inter birth interval; the motive of previous cesarean section; the technique used and postoperative complications. Each item was rated from 1 to 3 with the lowest rating indicating the least desirable situation for positive outcomes. The total score is obtained by simply adding the points assigned to each item. Exclusion criteria were: patients who normally met the inclusion criteria but had a disability or another factor superimposed such as HIV infection, non-consent and no cooperation of the woman. Similarly pregnant with unfavorable Bishop score (which means <7), were not part of the study. The minimum sample size for the study was estimated at 73, according to Schwartz formula with p = 0.05.

2.1 Intervention protocol and monitoring tools

The labour induction was done by intravenous infusion of low dose synthetic oxytocin (Syntocinon *) which was gradually increased, usually 0.5-1 mU / minute, and an incremental 1 mU / minute every 15 minutes. [3] With no electric syringe, the 5U oxytocin was diluted in 500ml 5% glucose serum.

The protocol consists of beginning with a rate of 4 drops per minute then gradually increase the dose every 15 minutes with an additional 4 drops (without exceeding 32 drops per minute) whilst monitoring the uterus response. A partograph proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) was used as monitoring tool. The outcome of the induced labour was assessed using a set of criteria which includes the mode of delivery, the state of the newborn at birth, and maternal morbidity and mortality.

2.2 Data collection, management and analysis

The data were collected and reported on a survey form developed for this purpose. We used doubled data entry and analyzed the data using SPSS software. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics (frequencies) and inferential statistics such as Chi2 test. Statistical significance level was considered achieved when the p-value is less than 0.05.

2.3 Ethics

For ethical considerations informed consent was obtained from patients (admitted pregnant women) and parents before applying the induced labour protocol. The study was authorized by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Lagune Mother-Child University Hospital in Cotonou, Benin.

3. Results

3.1 Frequency distribution of scarred uterus at HOMEL hospital

Between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2010, 24,006 deliveries were recorded at the hospital, among whom 1,596 births on uniscarred uterus (2.17% of deliveries). Among these deliveries of scarred uterus 1,094 (68,5%) were by elective cesarean sections (before start of labour). Among the remaining 502 pregnancies, labor was spontaneous in 384 cases (24,1%), and in 118 cases (7,4%) labour was induced. Our study focused on the latter group. The average frequency of labour induction on scarred uterus at the HOMEL hospital was thus 7,4% over the period of the study.

3.2 Sample characteristics of women and newborns

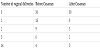

The average age of patients in the series was 30 years old (95% CI: 24-32). Parity ranged from 1 to 2 in 72.38% of cases. Patients were divided according to the history of vaginal birthing as presented in Table 1. In the group of women with history of cesarean section, 43.81% of the cases had a history of vaginal birth before cesarean section compared to only 23.81% of the cases who had a history of vaginal birth after the caesarean section. The main indication for previous cesareans was the fetal asphyxia in 41.90% of cases. The median birth interval (last two births) was 3 years, with extremes of 1 and 17 years. Gestational age was between 39 and 41 amenorrhea weeks in 81.90% of cases. The estimated fetal weight on ultrasound ranged from 2400g to 4000g.

3.3 Labour inducing and prognosis

The Bishop score at admission was favorable (> or equal to 7) in all pregnant women included in the study. These patients received oxytocin infusion regardless of the state of the membranes. The artificial rupture of membranes was in 93.33% of cases. The overall duration of the inducement ranged from 6 to 10 hours. For the majority of patients (86.02%), it was necessary to perform an artificial rupture of membranes at the onset of the first uterine contractions.

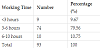

With the oxytocin infusion, all pregnant entered into an active phase of labour except in one case for whom the indication for the previous cesarean was dynamic dystocia. The triggering of labour has resulted in vaginal birth in 94.29% of cases, followed systematically with uterus revision. This uterus revision revealed a case of dehiscence of the scar. The induced labour failed in 6 women and the team resorted to cesarean section because of an acute fetal distress at the beginning of the active phase, cervical dystocia, or head engagement obstruction related to macrosomia (birth weight 4200 Grammes). The average duration of the labour was 3 to 6 hours in 65.71% of cases (Table 2).

3.4 Perinatal and maternal prognosis

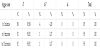

Perinatal prognosis is based on the condition of the newborn at birth, assessed by the Apgar score (Table 3). All 118 children were born alive. Apgar score at the 1st minute was well above 7 in 89.52% of cases. Four newborns had an Apgar score of between 4 and 7 and were all resuscitated with an improved Apgar score except in one case with whom Apgar score at 10 minute was unchanged between 4 and 7. Among these resuscitated children, two were born by caesarean section for acute fetal distress with initial Apgar scores in the first minute of 4 and 5. Three newborns were transferred in neonatology for intensive care. These were two newborns, born by caesarean section for acute fetal distress and an infant born to a woman in labor who had an ovular infection during labor. They were referred to intensive care unit for neonatal brain damage and for suspected neonatal infection respectively. A case of neonatal death was recorded in a newborn who presented a maternal-fetal infection with ovular infection in the mother. The neonatal mortality rate was 1.07%. For the mothers, the morbidity was marked by postpartum hemorrhage (3 cases), placental retentions (2 cases), one case of uterine atony with a woman of 41 years of age with 7 pregnancies and 6 deliveries, and one case of scar dehiscence (on a women with short birth interval) diagnosed during the uterus revisions and which required a laparotomy as conservative treatment. There was a complete perineal tear with one woman who had never delivered vaginally. No maternal death was recorded.

4. Discussion

4.1 Frequency of induced labour on scarred uterus

To reduce the high rate of cesarean in developing countries, two strategies could be considered: reduce the frequency of new indications through refocused antenatal care and adequate basic emergency obstetric care and reduce the iterative cesarean rates. Conducting vaginal birth in a scarred uterus is a scary situation for many obstetricians, particularly in developing countries where appropriate means for monitoring labour are not always available. This explains the low average rate of labour inducement on scarred uterus of 1.18% in our developing countries contexts compared to the rate of 7.85% recorded in Western study [4] . The fear of uterine rupture is the main obstacle to conducting any uterine test, which was only done in Benin in case of spontaneous labour.

4.2 Sample characteristics

First we need to discuss whether women in this series are different from women attending HOMEL generally. Then we will talk about the other demographics and clinical factors.

Pregnant women were selected based on a set of factors and criteria that may influence the outcome of inducing labour on scarred uterus. The woman’s age in this study was not a criterion for non-inclusion. For some authors, 35 years and older could increase the risk of for the vaginal delivery after a cesarean section. In our series the average age was 30 years old. In a study by Ecker et al, the cesarean section rate rose with age, 1and was 1.6% in the under 25 group compared to 43.1% for patients aged 40 and older [5] . Other authors have shown that history of vaginal delivery history was a favorable factor for the success of a uterine test [6] . This history indeed eliminates the risk of obstructed labour related to narrowed basins. Thirty-seven out of 93 women (39.78%) in our study had already had vaginal delivery at least once before the caesarean section. For Dommesent [7] , this factor does not appear to significantly alter the results, the success of cervix maturation or the mode of delivery. The main indications of previous cesarean sections in our series were non-permanent causes such as acute fetal distress; toxemia gravidae and babies presentations other than normal head presentation. All non-removable causes were exclusion criteria, although some authors have argued that one cannot predict the outcome of the labour from history of dystocia, whether mechanical or dynamic [8] . The birth interval may also influence the outcome of the labour inducement on scarred uterus. The median of the birth interval in this study was 3 years (ranging from 1 to 17 years). A short birth interval is recognized as a risk factor for uterine rupture in vaginal deliveries on scarred uterus. The risk is three times higher in case of labour inducement performed within 18 months after cesarean section compared to normal interval (24 months and over) [9] and thus most authors agree on a safety period between 18 and 24 months after a caesarean section. The pregnancy term also influences the outcome of the delivery on scarred uterus. In this series, the term was between 35 and 41 amenorrhea weeks +/- 4 days. There is no consensus on the threshold for gestational age; whilst some refer to 39 amenorrhea weeks, others consider 40 amenorrhea weeks as the term beyond which failure rate of uterine test is high. This is also the case for induced labour before pregnancies reach their terms [10] . The estimated fetal weight is another factor to consider as prognosis for the success of induced labour on scarred uterus. In this series the fetal weight ranged between 2400 and 4000 g. Although the sensitivity and specificity of sonography in detecting macrosomia remain limited due to technical margins in fetal biometry, the chance of success of vaginal delivery after cesarean section significantly decreases above 4000 g with an increased risk of ruptured uterus [1,2,3].

4.3 Labour onset

The cervical maturation may precede the onset of labour when the Bishop score is unfavorable. It was not necessary in our study, one of the inclusion criteria being a favorable Bishop score. A metaanalysis of 18 trials had found a vaginal birth rate of 76.5% within 24 hours [11] . However, the use of misoprostol is not without risk. Wing [12] stopped prematurely in 1998 a randomized study comparing misoprostol and oxytocin on scarred uterus, having found two ruptured uterus among the 17 cervical maturation using misoprostol. A year later, Plaut, after a review of all published cases of ruptured uterus occurred during the use of misoprostol on scarred uterus concluded on its high risk, with 5 cases of ruptured uterus out of 89 [13] . But since these experiences, the use of the prostaglandin is better codified especially in the doses and administration time. Faced with the fear of ruptured uterus associated with prostaglandins many teams are increasingly using mechanical means such as using the Foley catheter for cervical maturation. In obstetric practice in Cotonou, this alternative is reserved for cases of fetal death in utero on scarred uterus. It was not used in this study. The onset of active phase of labour was 98.92%. It does not appreciate the success of the induced labour, which was evaluated by the rate of vaginal delivery. The use of oxytocin on scarred uterus has demonstrated its efficacy and safety. A meta-analysis of 26 publications involving over 34,000 patients with previous cesarean section among whom 6208 had received oxytocin to initiate or manage labour found no significant difference between oxytocin and no oxytocin groups [14] . The authors concluded that in the response of scarred uterus to stimulation by the exogenous oxytocin was identical to that of healthy uterus. And if scarred uterus is capable of supporting spontaneous uterine contractions, it can support those induced by oxytocin. In our study the rate of vaginal delivery was 93.54%. The success rate varies according to studies, around 80.40%. [15] The use of oxytocin infusion score in our study provided a better selection of pregnant women and may explain this difference in our study. For many authors, the Bishop score was the best predictor of the delivery route in women with history of cesarean sections. When it was less than 3 at the onset, the likelihood of a caesarean section for addressing the failure of labour was significant. [16] The uterus revision was systematic in our study. It helped to diagnose two cases of partial placental retention and a case of uterine scar dehiscence. This practice is not shared by all authors. For Perrotin [17] , ruptured uterus were sufficiently symptomatic for a diagnosis to be revealed through uterus revision. In the immediate postpartum period, a comparative prospective study had revealed a greater frequency of occurrence of febrile illness and prescription of antibiotics in the group systematically uterus revision compared to patients who did not benefit from this procedure. Six (6) women in our series, the induced labour had ended with a cesarean section (a rate of 6.45%). This rate was 20.40% in the series of McNally on a sample of 103 women in labor. Suspicion of ruptured uterus, according to the publications was responsible for stopping the trial of labor in 1.5 to 9, 85% of cases [18] ; but this rupture is confirmed only in less than half the time.

4.4 Perinatal and maternal prognosis

All the children were born alive with an average Apgar score at the 1st minute > 7 in 95.69% of cases. Apgar average score in the 1st minute was 9.073 in Leng series [19] after induced labour on scarred uterus using oxytocin whether or not preceded by cervical ripening [19] . The Apgar score remained satisfactory at 5th minute in our study, and we may conclude that induction of labor on scarred uterus does not appear to be detrimental to newborns in our series, despite a case of neonatal death recorded in a context of neonatal infection.

The maternal prognosis was dominated by the immediate postpartum hemorrhage (3.22%), one case of dehiscence of the scar and zero maternal mortality. Although ruptured uterus was observed in Ben Regaya’s series (3% in a sample of 100) [4] , we did not observed a ruptured uterus in this study.

5. Conclusion

Induced labour in a context of scarred uterus is a fairly recent medical practice in the main maternity hospital in Cotonou, Benin. Despite the limited working conditions, and the small sample size of 118 cases, the initial results are satisfactory. Improving the outcomes of this practice whilst managing the real risks for mothers and babies would require a careful review of eligibility criteria (women’s age, vaginal birth history, gestational age, birth interval, reasons for previous cesarean section, estimated fetal weight and whether or not there is a cervical ripening would be required), quality monitoring of the protocol and the procedures and effective preparedness and response shall an emergency caesarean section be needed.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.