1. Background

The study described in this paper was devised to compare the effectiveness of early intervention on two groups of infants and toddlers who received treatment intervention for autism with the Mifne Approach [1]. The Mifne Approach provides early therapeutic intervention for infants and toddlers with autism and their nuclear families. It is based on family systematic therapy and attachment theory. The treatment program focuses on the entire range of the infant’s developmental components - physical, sensory, motor, emotional, and cognitive. The core component of the intensive therapeutic intervention consists of a residential program occurring over a three-week period. The family component of the program is designed to help the parents improve their awareness of their life and needs. The infant-directed therapeutic technique is called Reciprocal Play Therapy (RPT), which focuses on the whole range of physical, sensory, motor, emotional, cognitive aspects. While both groups of infants and toddlers participating in this study received therapeutic intervention with the Mifne Approach, the particular therapeutic techniques applied were personalized in terms of the age as well as the particular clinical symptoms of each individual child. It is important to emphasize that the focus of this study was not on the Mifne Approach per se, but rather on whether two groups of infants and toddlers differentiated in terms of age could be distinguished in terms of therapeutic response.

2. The Mifne Method Therapeutic Intervention Program

The Mifne Center had pioneered the treatment of toddlers with autism since 1987. The Mifne Center started in 2001 to treat infants and toddlers from 12-36 months, together with their nuclear families. Depending on their age, these infants either have a diagnosis of ASD or suspected as being high-risk for the diagnosis of ASD. The therapeutic approach at the Mifne Center is based on the attachment theory [2] and family therapy. Attachment theory informs the therapeutic approach; while not all attachment disorders in infants presage the development of autism, most autistic disorders involve an attachment disorder in different ranges of severity. At the Mifne Center the nuclear family has a focal role in the therapy. A family is an independent unit that undergoes internal dynamic processes by means of each one of its components, and the sum of the interaction between them [3,4]. Since autism may influence each of the family members, experience in this field shows that therapeutic intervention in the dynamic processes of the family, and the acquisition of coping skills, can lead to significant changes in their mutual relationships. The Mifne Center provides supportive therapy for each family member in addition to the direct treatment intervention for the infant with autism.

The Mifne Center provides a three-stage treatment framework:

- Three-week intensive treatment intervention for the infant involving family therapy

- Aftercare treatment in the family home under supervision

- Integration in kindergarten with accompanying supervision

2.1 Therapeutic approach

The therapeutic staff includes experts from the fields of medicine, psychology, psychotherapy, family therapy, and infant development who have been specially trained to work with the Mifne Method treatment intervention. The therapeutic approach is holistic and combines mental, bio-psycho-social and environmental aspects [5]. The program encompasses the entire nuclear family, since the parents are the main resource for their children and are especially important in helping to promote their children’s development during the stages of early infancy. The treatment program focuses on the entire range of the infant’s developmental components - physical, sensory, motor, emotional, and cognitive. The core intervention for the infants is a method developed to help the infant discover the sense of self and the pleasure of human contact. As Daniel Stern [6] describes, the main phases in the process of the development of the self in fact occur during the first year of life within the context of the mother-child relationship. Yet, development of the self is one of the core impairments in the phenomenon of autism [7]. The goal of the treatment is to enable the growth of self-confidence, trust and to stimulate the infant’s motivation to engage in social interaction.

2.2 The playroom

The playroom forms the center of the treatment intervention upon which all others revolve. The infant becomes involved in playful interaction with a therapist and/or parents in a playroom seven days a week for generally 8 hours a day. The therapists also observe the parents interacting with their infant in the playroom and provide individualized feedback and training to the parents regarding their playful interaction with their infant. Parental participation in the playroom and the feedback resulting from this process consists a large part of the therapeutic intervention.

2.3 Reciprocal play therapy (RPT)

Play is an optimal state in which the child can implement his abilities and express curiosity, creativity and joy. Various qualities of the bond between a parent and child are also manifested in play [6]. It is an activity that is bound by rules, time and space. The importance of play in the development of the self-derives from the connection between play and the child’s ability of representation [8].

The Mifne Method treatment intervention incorporates a method of play specifically devised for infants and toddlers with autism or its prodrome, called Reciprocal Play Therapy (RPT). RPT consists of three components, which may occur in parallel, i.e., attractive play; sensory play, emotional play, and cognitive play.

- Attractive play: Occurs, for example, when the therapist or parent attracts the infant’s attention with a favorite toy or object. When the infant tries to grasp the favored object, he may also pay attention to the therapist or parent, thereby establishing trust and mutual enjoyment.

- Sensory play: The therapist or parent gradually touches the infant, gives him hugs or massage, or takes him into her hands and attempts to make him feel at ease as much as possible. Often this sensory stimulation leads to new expressions of feelings and emotions, for example through smiling or crying.

- Emotional play: By means of play, the child can try out, learn to process content and cope both with the threatening reality and with fears from his inner world, through enjoyment and mutuality. Play, therefore, is one mean of the development of the ability to think symbolically - the representational ability.

- Cognitive play: The focus is in developing basic cognitive skills such as searching for a missing part of a toy, placing blocks together to build a tower, looking at a book, etc.

The play therapy is a cumulative process whereby every stage integrates elements from the previous ones. Through experiential play the infant develops an interactive play repertoire and thereby develops at his own pace. During a typical RPT treatment session a therapist may initiate playful interaction in fourstages, which may occur gradually or simultaneously: Firstly, close observation of the infant’s behaviour; secondly, engaging eye-contact; and thirdly, initiating a playful interaction. The therapist’s empathic interaction with the infant forms the basis of developing trust that will also inform the triadic therapeutic relationship developing between therapist, parents and their infant during the course of the treatment intervention. Every therapeutic encounter is both highly structured following defined clinical guidelines and allows for real-time improvisation, the therapist responding to a specific action or behaviour by the infant in a particular moment. The specific playful interaction will be tailormade for the particular infant as determined by the clinical team together with the parents. A daily therapeutic schedule is developed during the treatment according to the specific needs and habits of the infant. The daily schedule can be described as a combination of containment and flow within a highly structured therapeutic environment. Incremental adjustments to the daily routine are slowly incorporated to meet identified therapeutic goals. Rather than a specific technique, the therapist seeks to establish a fluid empathic connection or dyadic state of attunement with the infant [6]. The multidisciplinary nature of the therapeutic team means that different kinds of empathic relationships will be fostered. Similarly, different kinds of neurodevelopmental stimulation will emerge through the play therapy. For example, helping the infant to slide down an elevated ramp, to take one of numerous examples of play, may stimulate touch, sensory-motor coordination, social interaction, trust, joint attention, delayed gratification, cognition, etc. Initially, the infant’s initiatives guide the therapist’s attempt to develop reciprocal interaction with the expectation that a more natural attachment will develop between the infant and the parents.

2.4 Parental participation

Parental participation in therapy is a core component of the therapeutic intervention. Parents are empowered to ask themselves questions at each step of the therapeutic intervention in order to enable them to find their own answers to their dilemmas [3]. Parents may view the therapeutic interaction through a one-way mirror. Personalized feedback sessions are provided to the infant’s parents in order to facilitate their internalization and implementation of therapeutic insights and behaviors in their daily lives. All the therapy sessions are filmed [9]. This documentation is an integral part of the work in the playroom. The material is an educational resource for parental feedback, staff training, as well as for research conducted at the Mifne Center. Treatment continues at home with counselling and supervision on a regular basis by the Center’s clinical staff.

3. Methods

This study analysed two groups of infants and toddlers who received the Mifne Approach treatment intervention for infants with autism and their nuclear families. The first group consisted of 39 toddlers aged between 24-36 months who had a diagnosis of ASD; the second group consisted of 45 infants aged between 12-24 months, 38 infants were diagnosed with ASD and 7 infants were assessed at high-risk for autism.

Both groups were referred by various medical clinics as well as through self-referrals. Since the participants were first diagnosed in different locations and there was no standardization of diagnostic tools [10] all of them were re-assessed by child development experts external to the Mifne Center using early assessment screening scales depending on the age of the infant or toddler. The screening scales used for assessment of infants included: the screening scale ESPASSI© [11] applied from 5-15 months, and the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) applied from 16-30 months. The toddlers were assessed by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale for Toddlers (ADOS-T) generally applied from 24-36 months. In the older group all the 39 toddlers were diagnosed before treatment with ASD. In the younger group, 38 infants were diagnosed with ASD, and 7 infants were assessed to be at high-risk of autism.

The studied data was divided into four categories based on behavioural symptoms related to autism. These 4 categories consisted of: Engagement, [12-17]. Play, [18-20]. Communication, [21,22]. Functioning, [23-28]. Engagement components include: Eye contact, physical contact, obsessions, detachment. Play components include: curiosity, concentration, creativity and ritualistic behaviour. Communication Components include: pointing, vocals, speech, comprehension of situation, language comprehension, hand pulling and screaming. Functioning components include: fine motor coordination, gross motor co-ordination, eating manner, eating amount and hygiene (this last category of hygiene only applied to the older group of toddlers).

These four clinical categories were systematically recorded in the Daily Evaluation Scale Analysis (DEOS). The DEOS [8] is a clinical assessment scale for the analysis of reports of observations structured with the above variables used by therapists for the analysis of their reports following the treatment sessions, and has been implemented into the Mifne Center’s therapeutic program since 1996.

At the end of each session the therapist completed a DEOS form, checking it against her experiences during the session with the infant. The data are monitored after each session, every day, from the first till the last day of therapy. Collecting the data gives an insight to the therapeutic process and helps to focus on the infant’s specific needs as well as capabilities. Most behavior elements are scored on a scale from one to ten according to their frequency of occurrence as well as their quality; the numerical scores are supplemented by written verbal comments provided by therapists. The DEOS was analysed weekly during the first intensive treatment stage and every two months during aftercare treatment program.

The main clinical data was derived from video-records, therapist’s daily reports, and parents’ responses to questionnaires and interviews. Since all of the treatment sessions were filmed, the videos of these sessions provided a rich source of clinical data about each infant, as well as the interaction between the infant and parents. Following a treatment session, the camera operator completed a report form, which included the infant’s name, the code of the storage system, the therapist’s name, date and time, and a short description of activities done during the session and level of interaction done during each activity. The video records provided a digital archive for researchers to re-evaluate and confirm the clinical impressions registered by the therapists in the DEOS. In addition, a descriptive narrative was written by the therapist each day during the treatment of the infant. This report is read at the end of the day by a senior therapist and is incorporated into the research data.

Parental questionnaires and interviews at the beginning and during the duration of the intervention provided the final source of clinical information to build a comprehensive clinical picture of the family environment, as well as infant’s baseline assessment. Information provided refers, for example, to parental mental well-being, parental relationship, parental confidence, over protection of their children, level of stress, and level of the crisis they experienced at that stage.

Together, the video recordings, therapist reports, parental questionnaires and interviews provided qualitative data that informed the assessment of the four clinical categories contained in the DEOS form the basis of this study. The DEOS data of the group infants who were treated between 12-24 and the group of toddlers between 24-36 months was analysed statistically through the t-test for independent groups paired performed between the ‘pre-treatment’ mean (at the beginning of treatment) and the ‘post-treatment’ mean for each of the variables in each age group separately.

4. Results

The differences in results between infants who were treated between 12-24 and toddlers between 24-36 months are seen in the following t-tests for independent groups paired performed between the ‘pre-treatment’ mean and the ‘post-treatment’ mean for each of the variables in each age group separately. Each table is divided into three sections: pre-treatment, post-treatment, and the difference between pre- and post-treatment.

4.1 Engagement components

Eye Contact, Physical Contact, Obsessions, Detachment

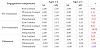

Table 1 shows the results of t-tests for engagement components which included: eye contact, physical contact, obsessions and detachment. Improvement in eye contact and physical contact is reflected through the measurement an increase in values; while improvement in obsession and detachment behaviour is reflected through the measurement of a decrease in values at the end of the therapeutic intervention.

At the pre-treatment stage there was no significant difference in eye contact between the two groups. For the rest of the variables, the younger group of infants showed better pre-treatment indices than the group of toddlers. Post-treatment results demonstrated significant clinical improvement for all of the four variables in both groups; however the positive impact of the treatment intervention on the younger group of infants was clearly much greater than on the group of toddlers. In other words, there was a positive therapeutic effect on engagement variables in both groups, but the positive impact on the younger group of infants was clearly much greater than on the group of toddlers.

4.2 Play components

Curiosity; Concentration; Creativity; Ritualistic

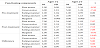

The play variables assessed in Table 2 included: curiosity, concentration, structured, creativity and structured/ritualistic play. Improvement in curiosity, concentration, creativity is reflected in the measurement of an increase in values; while improvement in structured/ritualistic play is reflected through the measurement of a decrease in values at the end of the therapeutic intervention. At the pre-treatment stage there was no significant difference in curiosity between the two groups. For structured/ritualistic play the younger group of infants showed better indices than the group of toddlers. For the two variables: concentration and creativity the group of toddlers demonstrated clearly better indices than the younger group of infants. This situation changed significantly at post-treatment.

4.3 Communication components

Pointing; Vocals; Speech; Situation Comprehension; Hand Pulling; Screaming

The communication variables assessed in Table 3 include: pointing, vocals, speech, situation comprehension, language comprehension, hand-pulling and screaming. Improvement in pointing, vocals, speech, and situation comprehension is reflected through the measurement of an increase in values; while improvement in handpulling and screaming is reflected through the measurement of a decrease in values at the end of the therapeutic intervention.

At the pre-treatment stage there was no significant difference in screaming between the two groups. For two variables: pointing and hand-pulling, the younger group of infants showed better indices at this stage than the group of toddlers. This situation changed significantly following treatment. Both groups exhibited an improvement in all variables without exception, however the younger group of infants clearly improved more significantly than the group of toddlers.

4.4 Functioning components

Fine Motor; Gross Motor; Eating Manner; Eating Amount; Hygiene

The functioning variables assessed in Table 4 included: fine motor, gross motor, eating manner, eating amount, and hygiene. Obviously, toddlers above the age of 24 months are more advanced in terms of motor skills than infants between 12-24 months. In this section all of the variables were positive - positive variables refer to an improvement through the intervention reflected in higher values.

At the pre-treatment stage there was no significant difference in the variables associated with eating, i.e., eating manner and eating amount between the two groups. In terms of the other motoric symptoms, fine motor movements and gross motor movements, the group of toddlers demonstrated clearly better indices than the younger group of infants.

Both groups exhibited an improvement in all variables; however, the younger group of infants clearly improved more significantly than the group of toddlers. There was a positive therapeutic effect on functioning variables for all infants in both groups, but the positive impact on the younger group of infants was clearly much greater than on the group of toddlers. For the component of gross motor movement there was no post-treatment difference between the two groups. However, the starting point for the group of infants (3.00) was well below that of the toddler group (5.00).

4.5 Evaluating the Delta between the two groups

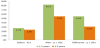

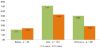

The results of the t-tests clearly demonstrate that while improvement occurred among both infants and toddlers in all categories of neurodevelopmental behaviours associated with autism, there was a significantly greater improvement among the younger group of infants between 12-24 months, than the older group of toddlers between 24-36 months of age. These findings are even more striking when considering the delta between the two groups: These findings indicate that for all four components the younger group of infants improved more significantly than the group of toddlers, despite the toddler’s group better starting point. These findings are presented in the following graphs (Figure 1-4).

In summary, post-treatment results in terms of the delta between the two groups demonstrated significant clinical improvement for all of the four variables in both groups; however, the positive impact of the treatment intervention on the younger group of infants was clearly much greater than on the group of toddlers.

5. Discussion

This study provides the first study comparing the effects of intervention for a group of infants between 12-24 months and a group of toddlers between 24-36 months. While both groups of infants benefited from The Mifne Approach intervention, the younger group demonstrated more significant improvements across all measured variables, including components for engagement, play, communication, and functioning. Note for example the t-test results between the group of infants and toddlers for Engagement Component of Eye Contact: (Pre-treatment t = 0.00; p< .000; Post-treatment t = 7.49; p< .000; Difference between the two group's pre-and post-treatment t = 5.63; p< .000). This finding is even more striking when considering the delta between the two groups: these findings clearly demonstrate that for all four variables the younger group of infants improved more significantly than the group of toddlers. For example, in terms of the obsession variable, the younger group of infants improved twice as much as the group of toddlers. These findings were observed even in relation to variables where the infants aged 12-24 months showed more severe age-appropriate pre-treatment signs of ASD than the older group of toddlers aged 24-36 months, including components of communication (vocalization, speech, situation comprehension and language comprehension - see, Table 3), play (concentration and creativity - see Table 2) and functioning (fine motor activity - see Table 4).

It makes sense that early detection and intervention will affect neuroanatomical development at a stage which is most influential for the rapidly developing brain, even to the extent that the full-blown later manifestation of autism can be prevented from escalation. Decades of neural, cognitive and behavioral research affirms that the human brain undergoes its most substantial and maximal development in the early postnatal years. As described by Elsabbagh & Johnson [29], the brain is a self-organizing system. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in earlier developing structures will have consequences for later developing structures. Deficiency of one variable will have impact on other variables. For example; the combination of motor developmental difficulties and lack of eye contact may have impact on environmental perception and thus may lead to Apraxia among other difficulties [30]. Early intervention is critical not only for the infant’s development but also for family processes that need support and guidance from the very first moments after identification of the infant’s development difficulties [1]. For example, addressing parental anxiety is important in alleviating psychological distress among parents of children with the prodrome of autism, that if untreated may lead to a vicious cycle of emotional distress, aggravating the affected child’s autistic symptoms.

Many research studies refer to early intervention from around 3 years of age. However, the Mifne Approach defines early intervention as occurring within the first two years of life, considering that the therapeutic window of opportunity is maximal up till the end of the second year of life - when the precursor neurodevelopmental variables associated with the prodrome of autism may be first detected. The question of the effectiveness of particular early intervention therapeutic techniques for infants and toddlers with autism requires further intensive investigation.

6. Conclusions

The two followed studies described in this issue present a comprehensive picture of different aspects relating to early assessment and intervention of infants with the prodrome of autism. The first study, “A Retrospective Study of Prodromal Variables Associated with Autism Among a Global Group of Infants during their First Fifteen Months of Life,” conducted base-line research into the early screening variables associated with the prodrome of autism.

The second study, “A Comparative Study of Infants and Toddlers Treated with The Mifne Approach Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder,” highlighted the importance of early intervention for the prodrome of autism. The earlier the therapeutic intervention, the greater the likelihood of achieving an effective therapeutic outcome in ameliorating the symptoms associated with autism.

Treatment in infancy is advantageous because of the plasticity of the brain at this stage. In the first two years of life the most accelerated growth of neurons takes place in the brain. These neurons are built into a complex web of cells that controls the infant’s sensoryemotional- cognitive regulation.

Bringing together summaries of these two research studies coming out of clinical practice is intended to help bridge the gap between early detection of the prodrome of autism in infants and therapeutic intervention.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.