1. Introduction

1.1 A journey of financial crisis

The global financial crisis in 2008 has brought a period of insecurity and stress and anxiety worldwide, with Greece among the major recipients of this turmoil. Namely, in the European Union there was a long lasting economic division between the rich countries of the North and their southern partners (also called during the Eurozone crisis by some press media ‘PIIGS’ i.e. Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain) that were the so called “consumption-led countries” (better defined as ‘services led countries’) and had larger deficits and debts [1]. Rather than showing a sense of solidarity, the international and European authorities questioned the political decisions of democratically elected governments and imposed fiscal contraction, which led economies to further stagnation and dramatic worsening of the GDP and outcomes as will be discussed below [2,3] . In order to be more specific we can take the example of Germany and France, which tried to use every mean to save their own banks, thus affecting the bailout arrangements and exacerbating the consequences for the Greek economy.

By the end of 2009 Greece was at the brink of financial disaster with a double digit budget deficit. Six months after the general elections, the Hellenic Government announced spring 2010 the inability to pay its foreign and domestic debt and asked for help from the International Monetary Fund. Negotiations with international organizations and the European Union followed and a three part committee (with members from the International Monetary Fund - IMF, the European Commission -EC and the European Central Bank - ECB), the so called ‘Troika’, has been formed which followed the TINA logic (‘There Is No Alternative’ to austerity) and imposed a memorandum of agreement with severe austerity measures falsely considering the so called Greek problem as a local peculiarity [4,5] .

On May 2011 a package of financial measures was announced and during the following years two more memoranda (2012 and 2015) between the Greek Governments, the IMF, the EC and the ECB were signed imposing further austerity measures, while in June 2015 capital control measures were imposed leading to a further deterioration of the economic climate.

1.2 Consequences

Besides the political impact the crisis had many economic, social and humanitarian consequences. By 2013 the economy had shrunk by 23.5% in relation to 2007 causing a recession with unprecedented consequences. Unemployment peaked at 28% - which was twice the average Eurozone rate-while in young people it has soared to 60% (!!) causing a dramatic increase in poverty [4,6] . Moreover, a reform of the health care and pensions system with drastic restrictions resulted during 2012 in a significant increase of mortality and indeed at the higher level since 1949, with a further surge over the next years [7,8] especially affecting people chronically ill and older than 55 years.

In addition, a tendency towards attempted suicides recorded a significant increase over the first years followed by the Greek economic crisis [9]. Suicides increased by 50% within four years, i.e., from 328 cases in 2007 to 477 in 2011 [10]. Specific studies have shown that during the crisis there was a shift in the vulnerability of individuals to suicide and even more so for those who already had a psychopathological background [11]. On the other hand births decreased by 15% within the same period of four years 2008 - 2012.

1.3 Emotions and Conceptualisation

The term ‘crisis’ has been associated with agitated and painful circumstances involving the appearance of intense emotions [12]. Such a situation creates major social inequalities and gives rise to a multitude of complaints, a threat of mourning and many strong emotions i.e. disappointment, anger, fear, stress leading very often to helplessness and depression [13,14,4]. An economic crisis threatens people to lose valuable privileges and the prospect to have a vision for the future [4]. Lazarus [15] detected these emotional reactions as basic (anger, disgust, fear, anxiety, sadness) and social (shame, guilt, envy, jealousy).

According to Capelos and Exadaktylos [16], the Greek economic debt produced fear and anger to the public, affecting their behavior and opinion, addressing the strong relationship between emotions and beliefs. The crisis led to a strong public emotional reaction, and a lack of trust towards the governmental institutions and beliefs in democracy in Greece. This was confirmed in 2011 when the public conveying emotions of indignation and frustration following this financial standstill and the austerity measures, formed a wave of protest as will be described below.

People felt indignation and rage [17] also because besides political issues they considered that there were serious financial irregularities and accused them for “national treason”. Specifically, during the crisis years there were numerous reports about major politicians involved in financial scandals and crimes [1]. As a matter of fact, some cases ended in criminal justice with convictions and long imprisonments.

Moreover people felt very angry about the way the government presented the crisis aspects, the reasons, the assessments and the perspectives. For some years the headline news for Greece and the exchanges on social media were rather discouraging and disappointing. The politicians’ dialectic and discourse was not convincing and had not provided any kind of optimism for the near future contrary to what the role of a government would dictate [1].

Observing these events from a wider lens, the level of anger in Greek society rose a few years before and of course this crisis played its part, but as a cherry on the cake of an already angry society. It started from years without obvious financial crisis, or even years of prosperity, after the 2004 Olympics that filled the Greek people with pride in what the country achieved. During these years parts of society were so angry and outraged that the killing of a sixteen year old boy was enough to wreak havoc on the December 2008 outbreak. Facing this situation the government power felt weak to confront the uprising and the extensive looting, therefore police was not allowed to intervene and restore the city's proper functioning in order not to make things worse. So that was a sign of fear at the level of power during the pre-crisis years, which meant an indirect recognition of the inherent anger and the actions that drove it potentially (but also ontologically). Of course, many mass media outlets that like digestive explanations blamed the post-2010 crisis as the only reason for creating anger in the country.

Angry persons often feel being infallible and discontinue any attempt for communication. They cannot easily rationalize, perceive reality and make decisions because anger distorts the process of reasoning and masks the emotions that actually trigger it [18]. Furthermore, according to the Kübler-Ross model, anger is the second psychological response of grief after the appearance of denial. The humanistic experiential anger workshop created by Dr Callifronas considers this emotion as the buoy for an unmet need [19,20] . Anger is also a natural response to loss and can be a difficult emotion to cope with, since many of us will suppress this emotion, keeping it bottled up or even turning it inward, toward ourselves. Anger turned inward is guilt as to whether “we should have done something”, and this leads, through the feelings of helplessness, to depression.

In the past century anger has always been recognized as a major contributor to depression [21,22] , while anxiety was linked to curiosity [22,23] , since both of them appeared in order to react to a stimuli and avoid emotions of fear and insecurity [24]. According to Spielberger, anger, anxiety, curiosity and depression are significant indicators for mental health and are directly related to recent intense events [25]. Therefore, the Greek economic debt is considered as an event with a significant impact on the emotions of the Greek people.

1.4 Reactions

Jasper [26] argues that feeling and thinking are parallel processes of evaluation and interaction with our environment. So feelings of vulnerability push ideas to do something and react.

When media message triggers feelings of distress and sadness, people attribute blame to other non-company-related factors, while those who experience feelings of anger blame others on the situation and in the company [27,28] . In our case grievances and anger nurture a major motivation of collective action [29,30] . During all the austerity years in many European countries there has been a huge increase in street protests about grievances on austerity decisions by the governments [31,32] .

In Greece, the first package of austerity measures has led people to massive demonstrations and to create on May 2011 the movement of the “indignant” (aganaktismenoi) followed by tens of thousands of citizens [4]. They were camping as an act of protest at the Constitution square (Plateia Syntagmatos) for three months [33]. At national holiday parades, citizens were throwing tomatoes and yogurt and eggs to government officials and even to the President of the Hellenic Republic. Clashes with police were very frequent while radical actions, like acts of public disobedience, refusal to pay taxes and capture of highway tolls have been also often observed. These Reactions might have some common facets with the so called “Arab spring” [4].

2. Aim and Scope

Considering the consequences of the Greek financial crisis the assessment of the frequency and intensity of these emotional states is of great importance. Therefore, It is important to link these emotions to specific events in order to understand why people finding it difficult to adapt to new threatening everyday life challenges.

Accordingly since anxiety, anger, and depression are important indicators of psychological distress the financial crisis was hypothesized, as potentially having had important psychological impact on the Greek public. Our paper is aiming to describe the fluctuation of anger anxiety depression and curiosity during this critical period 2011-2016 based on spontaneous sampling of people aiming to participate in an anger workshop. The study starts in 2011 and examines the whole sequence of 6 years and how it developed throughout. We present the scores of six groups measuring dispositional anger, anxiety, curiosity and depression in a four-level Likert scale, using STPI (State -Trait Personality Inventory).

3. Material and Methods

As previously mentioned our paper describes the fluctuation of anger anxiety depression and curiosity during this critical period 2011- 2016 based on spontaneous sampling of people who participated in an introductory and informative session aiming to enroll in an anger workshop created by Dr M. Callifronas and the Hellenic Institute for Psychotherapy [19]. This programme is organized in collaboration with several municipal communities of Athens/Attica since 2007.

Participants (N = 157) came from the northern suburbs of Athens, had higher or middle education and belonged to the middle class. Participants’ age ranged from 36 to 55 years old. As previously described, our sample consists of persons who come spontaneously to attend the initial presentation of our anger lab in order to eventually enroll in this workshop. In our experience the audience is mainly consisted of women and there is a 4 to 1 or 5 to 1 ratio of women to men. In this specific sample the wide majority (87%) were also women.

As a measurement tool for personality traits, the self-administered State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI) was used, that consists of 80 questions measuring state and trait characters for anger, anxiety, curiosity and depression in a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 [25]. Our work examines the personality traits, since they offer greater evaluative/appraisal stability than the evaluation of the state characteristics which refer to the present moment and can be transitory. So each one of these four characters is examined by 10 items. Concerning the questions on anger these illustrate how often angry feelings are experienced over time. Additionally, it examines the individual differences that these feelings are experienced anger.

So, for example, questions like “I am a hot-headed person” or “I feel annoyed when I am not given recognition for doing good work” [34] are used to examine anger-related traits.

This paper studies a) the alteration of anger as personality trait during the examined years 2011 to 2016 b) the correlations between the traits of anger, curiosity, stress and depression during the examined period.

3.1 Null and alternative hypotheses

Our null hypothesis was that there was no (statistical) significant difference in fiuctuations of emotions over the years examined. The alternative hypothesis was that there was a significant difference between the years considered. Furthermore our null hypothesis was that there was no significant correlation, while the alternative hypothesis was that significant correlations would be observed.

4. Results

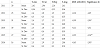

In Table 1 are shown the mean values and standard deviations of anxiety, anger, curiosity and depression traits observed during six consecutive years, 2011 to 2016 and the levels of significance for the differences concerning the anger traits. As can be noticed, the levels of anger show a continuous escalation with the highest level in 2016 one year after the imposition of the capital controls. As shown on the right side of the table, there is a noticeable difference in anger levels between year 2011 and years 2013, 2015 and 2016 which crosses the threshold of significance (*represents a significance of p<0.05, while **stands for the significance p<0.04). The ANOVA test did not show significance. Moreover the levels for anxiety, curiosity and depression traits did not show any significant fluctuation.

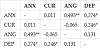

On the other hand, in Table 2 the correlations among the values of the four aforementioned traits are exposed. As can be observed remarkable correlations exist for the dyads anxiety/anger, anxiety/ depression and depression/curiosity. As far as significance is concerned * represents p<0.02, while ** symbolises p<0.01 [35-37,38].

5. Discussion

5.1 Fluctuations of emotions during the six years period

Economou et al. [39] as well as Christodoulou et al. [40] found a significant increase of suicides and suicidal attempts between 2008 and 2010 further strengthening during 2011 and 2012. They stated that major depression was the strongest risk factor for this increase. Chryssochoou et al. [4] in their study in a sample of indignant people protesting for austerity measures that was gathered in November - December 2011, showed anger indignation and rage 5,75 ± 1,4 (mean ± SD), fear and frustration 4,47 ± 1,27 and depressive state 2.08 ± 1.2 measuring on a 1 to 7 Likert scale.

Our data show that when the very first samples of our study were collected in 2011, we were already in a social climate full of tension with high anger levels. The controversial fact that our first sample, which was collected in May 2011, showed the lowest mean value (2,41 ± 0,56) for anger, when compared to the next years’ levels, could maybe explained by the point that our sample was gathered from people who realized themselves as being angry, were acknowledging their emotions and had taken responsibility for these emotions instead of protesting in manifestations. Following the next years (2012 -2016) our sample displayed a progressive increase, showing significant difference in anger levels for the years 2013, 2015 and reaching its highest level in 2016, one year after the imposition of capital controls in Greek banks and financial system. Unprocessed data from our sampling in 2018 presented also high levels of anger, which were quite similar with those of previous years (2.71±0.55).

Anger is considered as the emotion of collective action. However it is remarkable how throughout the years the manifestations of anger like street protests have been diminished. One explanation is that the activation changed aspect. Namely, instead of protesting about grievances in 2015 they radically changed their vote by bringing into power a movement that a few years before into represented a very small one digit electoral fraction. So, they kept all their hopes in this new government. However, since capital control measures were implied by this new government, their anger seems, according to our data to have grown in even higher levels. Citizens' reactions confirm that the basic constituents of cultures and people acting collectively are the common emotions associated with a specific objective or social issue [41]. According to Maher et al. [42], individualist cultures tend to focus on the desire of the individual rather than the group, whilst collectivist cultures are interested about the goals of the group first.

Another interesting result is the low level of depression that we found both at the start and throughout the study as well. No difference was found among the six years of the study. Low levels of depression have been also found by Chryssochoou et al. [4] in their study as previously described. Anger and combativeness can trigger collective action [4,30] and even actions of non - normative character [28], while having an inverse relationship with depression [4]. On the other hand poverty increases the depression levels and the thoughts to abandon life, since the number of alternatives is drastically reduced. Crosby [13] agrees with this rationality by arguing that feelings of fighting show that people believe in the existence of alternatives, thus having a negative relationship to depression. On the other hand, Kübler-Ross & Kessler [43] referring to the reaction of grief and loss considered anger as the second out of five stages and classified depression as the fourth stage, that can happen in an advanced phase of grief. So, the Kübler- Ross & Kessler classification clarifies the reason why depression is still in low levels during the period of our study.

Similar results have been observed concerning the levels of stress and curiosity throughout the years of our study: no significant levels in the beginning of the study as well as non significant changes throughout the years have been traced.

5.2 Correlations between the observed emotional states

According to Jin & Pang [44], anger, fear, anxiety and sadness are the main emotions that citizens can experience in crises situations. In organizational crises and corporate offenses the first feeling expressed by communities is anger. Fear is related to the public's uncertainty about how to deal with the loss. Anxiety is also experienced when the public is feeling emotionally charged and trying to seek direct solutions [27]. In contrast to anxiety, fear and anger, positive emotions, such as curiosity feelings, motivate the mind, thereby enhancing the ability to negotiate and solve problems, helping people make effective and right decisions [45].

As previously described, anger indignation and rage are emotions that often lead to collective actions. They are inversely connected to reactions of financial security and depression [4]. On the other hand, vulnerability, fear and frustration are major predictors of depression [4].

According to studies, the major changes, that crisis has brought in income and employment, have a significant impact on people's wellbeing. Unemployed people are experiencing feelings of worry and sadness, and also stress when the unemployment-to-income ratio is the highest. Unemployment is also linked to poor ratings for life [46]. Deaton (2011) studied the reactions of Americans and their well - being index during the years 2008-2010 and surprisingly found that the well-being was closely correlated and varied with the stock market fluctuations. Therefore, the repercussions of an economic crisis can cause anxiety and unsatisfactory feelings about life evaluation that are most likely to lead to depressive symptoms [46].

Moreover, Helliwell et al. [47], found that during and after the 2008 financial crisis, the rates of happiness in US population where associated also with unemployment and social capital. The same findings apply to European countries that have recovered from crisis. However, social capital and happiness were affected in countries which were most damaged by the crisis. Maybe this explains why in a country such as Greece with high social capital, levels of happiness have declined over the years followed by the crisis suggesting its strong impact on social engagement as well as increased depression rates.

Krackow and Rudolph [48] found that young people with depression have experienced more interpersonal and independent stress than their “healthy compatriots. Depressed youth also valued the stressful side of events more strongly, thereby showing a distorted appreciation of the situation. When anxiety or fear is experienced during a particular activity, these emotions will surface every time are repeated [49]. The fact that the financial crisis is linked to anxiety emotions leads people to recall these feelings every time they experience losses. As a result the anxiety grows stronger and leads to symptoms of depression and anger. They explained that according to the cognitive theory of depression, there is distorted processing, of stimuli and information received in stressful situations, which in turn increases the intensity of depression.

A paper by Callifronas and Kontou [19] in a similar (with ours) sample, showed a scalar increase of the anger and stress scores with a respective scalar decrease of the curiosity score which might probably show the reduction of creativity and resilience in periods of psychological distress. However, a higher number of participants were needed to statistically come to a conclusion, since their differences and correlations were not significant. Our data are in accordance with the above mentioned findings since we found that anxiety was significantly (p<0.05) correlated with depression.

Moreover, Sioussoura et al. [50] studied the prevalence of psychological distress anxiety and depression in 43 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Apart from the high frequency found in these clinical syndromes, there was a very high correlation between anxiety and depression scores (ρ= 0.86, p< 0.001). Although the instruments used in their work (HAMA and HAMD) were different from ours, their data seem to agree with our findings regarding the relationship anxiety-depression.

The connection between these two clinical entities has a logical explanation. High levels of anxiety and stress reduce the ability of cognitive functions, thus leading to feelings of weakness, inability and subsequently depression. On the other hand, depression brings anhedonia and reduced ability of attention which results in reduced efficiency in day-to-day operations, thus creating a stressful reaction.

A rather unexpected finding in our study is the correlation between curiosity and depression at the threshold of significance (p<0.05), which does not seem to be easily explained by the literature, since the depressive process is characterized by anhedonia, which by definition one is deprived of interest in anything new. A possible explanation would be the fact that in our sample we observed relatively low levels of depression. So the mood for curiosity in rather “dysthymic” levels had not been affected and would possibly show mobility for new ideas and ways to overcome the consequences of the financial crisis.

Another result worth commenting on here is the relationship between anger and anxiety, which according to the data presented in Table 2 revealed a significant (p <0.05) correlation . Namely, according to psychophysiological data both anger and anxiety are produced by reaction of the same brain site, the so-called locus coeruleus, which is based in the brain stem pons. So, their affinity can be easily understood.

It is noteworthy that although anger and anxiety values on the one hand and anxiety and depression values on the other are correlated, anger and depression showed no sign of correlating with each other. However, anger is bibliographically correlated to social mobilization [4], while depression is related to inactivity and abandonment of targets [13].

6. Conclusion

Our data show a significant increase in anger levels over the first six years of austerity measures, with the highest anger score in 2016, one year after the imposition of the capital control measures. These results imprint the high or very high levels of emotional reactions during the years of the Greek financial crisis. Furthermore, significant correlations between anger and stress as well as between stress and depression were observed, showing the high affinity between these emotional traits.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Credentials

Dr Michael Callifronas, (MD, ECP, AEU Paris, DCTP) is Physician,

Psychotherapist, Cert. Clinical Supervisor, Cert. Focusing Oriented

Therapist and Trainer, Author, Editor and Reviewer.

Mrs. Katerina Loukia Kaltsouni, (MSc) is Psychologist and Clinical

Neuropsychologist, working in the Hellenic Public Sector of Special

Education.

Dr Nikitas Patiniotis (PhD) is Professor Emer. for Sociology,

University of Patras and Panteion University, Athens.