1. Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) such as Facebook allow users to construct a public profile, create connections with others, share personal and social content, upload photos, and communicate through messaging and online real-time conversations [1,2]. Popular motivations for using SNSs relate to communication and connectedness with others [3,4], the need for extensive social and political engagement [5], avoidance of loneliness and boredom [6], enjoyment [7], escape from emotional frustrations [8], and selfesteem enhancement [9]. Research by Nadkarni and Hofmann [10] proposed that Facebook use is motivated by two primary needs: (1) the need to belong, and (2) the need for self-presentation. The authors argued that demographic and cultural factors contributed to the need to belong, whereas neuroticism, narcissism, shyness, self-esteem, and self-worth contributed to the need for self-presentation. The Uses and Gratifications theory (UG theory) [11] proposes that individuals actively use media to fulfil a need. Park, Kee and Valenzuela [5] revealed four primary needs to participating in Facebook; socializing, entertainment, self-status seeking, and information seeking. Pai and Arnott [12] identified four main values derived from SNS use; belonging, hedonism, self-esteem, and reciprocity. Altogether these motivations raise the assumption that Facebook use could plausibly have an impact on users’ life satisfaction.

Engagement with Facebook has been found to have positive and negative psychological impact on users. In terms of positive impact, Facebook use has been associated with increased social connections [13,14], self-esteem [15], enhanced identity development [16,17], increased social support, and decreased loneliness [18]. In terms of negative impact, problematic Facebook use has been associated with lower levels of belonging, self-esteem, and life satisfaction [19-21]. These studies raise the question of whether specific forms of Facebook use could be potentially associated with decreased life satisfaction.

Facebook allows for two different forms of use: Active Facebook Use (AFU) and Passive Facebook Use (PFU) [6,22]. AFU is characterized by communicating with others through messages or conversations and updating profiles. Conversely, PFU (or passive following) is characterized by only browsing the News Feed section, following communications and comments of online friends, and observing the profiles of others [6,22]. Passive following on SNSs has been found to decrease social capital and increase loneliness [18]. Tobin, Vanman, Verreynne, and Saeri [23] examined Facebook use amongst a sample of 89 frequent users that were instructed to use Facebook passively for 48 hours. Results showed that participants indicated lower levels of self-esteem, belonging, and meaningful existence. However, it was not clear whether the findings were due to passive following or the prohibition of active engagement. Research by Krasnova, Wenninger, Widjaja, & Buxmann [24] examined passive following among 584 Facebook users and reported that passive following exacerbates envious feelings which decreased life satisfaction. Passive following is linked to the theory of purposive value [25] which refers to the giving and receiving of information in virtual communities such as Facebook [26]. Park et al. [5] found that one of the reasons students used Facebook was to obtain information about events, products and services.

A possible explanation for the negative impact of passive following on Facebook could be inferred by considering the premises of social comparison theory [27], which suggests that people evaluate themselves in comparison to others. Buunk and Gibbons [28] reported that people who engage intensively in social comparison are uncertain about themselves. Thus, these individuals may use Facebook as a tool for self-evaluation and self-improvement. However, social comparison on Facebook is mainly negative, Chou and Edge [29] revealed that frequent comparison on Facebook leads to general dissatisfaction, fostering in individuals the feeling that their own lives are not good enough. Thus, social comparison could be an important feature of Facebook use that potentially affects life satisfaction. Research by Vigil and Wu [30] revealed that intense Facebook use caused a tendency, through social comparison, to decrease users’ levels of life satisfaction. Adolescents have been found to be more vulnerable to the negative effects of SNSs through developing negative self-perceptions [31], while intense Facebook use involves them in more passive negative social comparison [32]. In contrast, people in middle adulthood have already shaped their personality and developed mature mechanisms which help them to overcome the negative feelings associated with SNS use [33]. Steinfield, Ellison, and Lampe [34] reported that self-esteem and life satisfaction were related to bridging social capital amongst students, furthermore it was found that Facebook serves to reduce the barriers to interacting with weak ties for those with low self-esteem. Research by de Oliveira and Huertas [35] showed that participants with high life satisfaction were motivated to use Facebook. Seder and Oishi [36] reported that participants who exhibited a more intense smile in their Facebook photo had better future life satisfaction; this finding was partially mediated by first-semester social relationships satisfaction. These studies further underscore the need to investigate further the interplay between age, social comparison, and life satisfaction.

Recent studies have also found that fear of missing out (FoMO), which is the continuous desire to be connected online and worrying that others have more rewarding experiences from which one is absent, may impact on the life satisfaction of Facebook users [37]. FoMO may be contextualized within the self-determination theory [38] which proposes that self-regulation and psychological health are based on three basic psychological needs: efficacy, autonomy, and connectedness with others [39]. Facebook is an online world which allows users to meet these basic psychological needs through communication, self-presentation, and personal feedback [39]. Accordingly, Facebook users who engage with Facebook aiming to achieve these psychological needs tend to develop a general sensitivity to FoMO [37]. In previous studies, FoMO has been associated with high levels of stress [40], skipped meals [41], and sleep deprivation [42]. Research by Przybylski et al. [39] revealed that FoMO was positively associated with intense Facebook use and negatively associated with life satisfaction, and that high levels of FoMO was found in younger participants. This study provides evidence of a clear effect of FoMO on life satisfaction, further investigation of the relationship between FoMo and specific forms of Facebook use is needed.

Previous studies have identified associations between SNS use and wellbeing as well as gaps and limitations in the current understanding of Facebook use. Moreover, there is currently a scarcity of studies investigating passive following on Facebook and FoMO even though this is an area of growing academic interest as these variables may present potential psychological implications for SNS use. Furthermore, it is important to consider how the theory of purposive value [25] and the social comparison theory [27] relate to the variables of social comparison, life satisfaction, and self-esteem. Research has shown mixed results regarding self-esteem with it having both positive and negative links to Facebook use; this is an area in need of further investigation. Given the aforementioned rationale and the literature discussed, the main aim of the present study was to investigate how passive following on Facebook, FoMO, self-esteem, social comparison, and age may affect life satisfaction. To achieve this aim, the following hypotheses were developed:

H1) Passive following on Facebook will be negatively associated with

life satisfaction.

H2) Social comparison will be negatively associated with life

satisfaction.

H3) FoMo will be negatively associated with life satisfaction.

H4) FoMO will be positively associated with passive following on

Facebook

2. Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

An online survey was created with online survey software called Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). An anonymous hyperlink and message outlining the purpose of the study was generated and shared on several social media websites to allow potential participants to take part in the study. Data was collected between December 2016 and February 2017. A total of 196 participants were recruited using opportunity sampling. Of those, 152 (77.6%) were females and 44 males (22.4%) aged between 18 and 63 years old (Mean = 31.16, SD = 8.75). Moreover, more than half of all participants were residents of the United Kingdom (n= 108, 55.1%), the United States of America (n = 44, 22.4%), and Greece (n = 33, 16.8%), while the remaining 5.5% of participants (n = 11) were residents of other countries. In terms of participants’ occupation, the vast majority reported being ‘employed’ (74%), followed by ‘student’ (17.9%), ‘unemployed’ (6.6%), ‘other/selfemployed/ seeking employment (1%), and ‘retired’ (0.5%).

2.2 Ethics

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and adhering to the British Psychological Society ethical guidelines. The university’s ethics committee approved the study. All participants were informed about the study and all provided informed consent.

2.3 Measures

Demographic questions (i.e., age, gender, country of residence, occupation status) were asked at the beginning of the survey, there were also questions regarding general Facebook use (i.e., how long do you spend on Facebook each day? What are your most common Facebook activities?).

Passive following on Facebook was assessed with the three-item Passive Following Questionnaire [4], which asked participants to report how often they (a) ‘look through the News Feed section on Facebook’, (b) ‘look through the conversations their friends are having’, and (c) ‘browse others’ profiles’. All three items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I do not use Facebook) to 7 (I use Facebook several times a day) to examine to what extent participants engage passively with Facebook. The total score for each participant was calculated by summing the score from the three items with higher scores indicating high levels of passive following on Facebook. The Passive Following Questionnaire was found to exhibit adequate psychometric properties in previous research (e.g., [4]). Internal reliability in the present study was satisfactory (α = .64).

Social comparison was measured with The Social Comparison Scale [43] to assess participants’ self-perceptions about their social status and social standing. This scale includes a total of 11 bipolar statements about attractiveness, status, and fitting into society. Example statements include ‘in relation to others I feel: inferior or superior, untalented or more talented, unattractive or more attractive’. When responding, participants used a 10-point Likert scale to specify the intensity of their feelings for a given statement regarding how they perceived themselves in relation to other people. The scale ranged from 1 (unlikable or less talented) to 10 (more likeable or more talented). The total score for each participant was calculated by summing the score from all 11 statements with lower scores indicating feelings of inferiority and general low self-evaluation. The Social Comparison Scale was found to exhibit adequate psychometric properties in previous research (e.g., [43]). Internal reliability was also excellent in the current sample (α = .93).

Fear of Missing Out was measured by the Fear of Missing Out Scale [39] which contains 10 item asking participants about their everyday experience on Facebook, using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true of me) to 5 (extremely true of me). Sample items included, ‘I fear others have more rewarding experiences than me’ and ‘When I go on vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing’. The total score for each participant was calculated by summing the scores from all 10 items with lower scores indicating intense FoMO. The Fear of Missing Out Scale has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties [39], and its internal reliability was excellent in the present sample (α = .84).

Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [44]. This scale comprises a total of 5 positive and 5 negative statements of self-worth. Participants responded to all 10 items using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Sample items included, ‘On the whole, I am satisfied with myself ’ and ‘All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure’. The total score for each participant was calculated by summing up the scores from all ten items with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-esteem. The Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale was found to have excellent psychometric properties [45], and the internal reliability of the scale in the present sample was excellent (α = .87).

Satisfaction with Life Scale was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [46]. The SWLS comprises a total of 5 statements about global cognitive judgements of satisfaction with one’s own life. Participants indicated their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree) with statements such as, ‘In most ways, my life is close to my ideal’ and ‘If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing’. The total score for each participant was calculated by summing up the scores from all five statements with higher scores indicating higher life satisfaction. The SWLS was found to display excellent psychometric properties [46,47], and excellent internal reliability in the present sample (α= .90).

2.4 Data management and analytic strategy

Data were screened and checked for parametric assumptions through descriptive analysis. A series of Pearson correlation analyses were conducted with the aim to investigate the relationships between the variables of passive following, social comparison, FoMO, selfesteem, age, and life satisfaction (H1, H2, H3, and H4 respectively). A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate to what extent social comparison, FoMO, and self-esteem would predict overall life satisfaction. Assumptions of the multiple linear regression were checked prior to the estimation of the model. More specifically, an analysis of standard residuals was carried out, which showed that the data contained no univariate nor multivariate outliers that could bias the estimation. Furthermore, multicollinearity issues were checked using the tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) scores for each predictor variable in the model alongside the assumption of independent errors and non-zero variances. Sample size considerations were considered, and no issues were present as recent recommendations suggest at least two subjects per variable in a linear regression analysis [48]. All the assumptions were met and the multiple linear regression was computed using the enter method. All data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

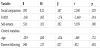

The mean length of time participants engaged with Facebook per day was 114.23 minutes (SD = 88.27). The most common Facebook activity reported (n= 139, 70.9%) was passive following (i.e., checking the News Feed; checking the profiles of other; checking comments; and conversations of others), while the second most common activity was chatting with friends (n= 44, 22.4%) (Table 1).

Mean scores indicated that the participants exhibited a moderate level of passive following (M = 14.7, SD = 3.71, min. = 4 – max = 21), social comparison (M = 63.70, SD = 19.65, min. = 11 – max = 105), FoMO (M = 21.42, SD = 7.35, min. = 10 – max = 43) and selfesteem (M = 21.33, SD = 4.86, min. = 9 – max = 30). Additionally, mean scores indicated that participants exhibited a high level of life satisfaction (M = 23.90, SD = 6.69, min. = 5 – max = 35).

3.2 Correlational analysis

A series of Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were computed to explore the potential relationships between passive following, social comparison, FoMO, self-esteem, and age with life satisfaction. The results of this analysis revealed that life satisfaction was not significantly associated with passive following on Facebook (r[194] = -.05, p= .257) but positively associated with social comparison (r[194] = .27, p< .001). These findings did not lend empirical support for H1 (i.e., passive following on Facebook will be negatively associated with life satisfaction) and H2 (i.e., social comparison will be negatively associated with life satisfaction). Furthermore, FoMO was negatively associated with life satisfaction (r[194] = -.33, p<.001), suggesting that people exhibiting less symptoms of FoMO tended to be more satisfied with their life. This result supported H3 (i.e., FoMo will be negatively associated with life satisfaction). Finally, results from the correlational analysis showed a significant positive correlation between FoMO and passive following (r[194] = .30, p< .001), this finding supported H4 (i.e., FoMO will be positively associated with passive following on Facebook). Other correlations showed that there was a significant negative correlation between age and FoMO (r[194] = -.210, p< .001), there was a significant negative correlation between age and self-esteem (r[194] = -.195, p< .001), and there was a significant positive correlation between age and life satisfaction (r[194] = .149, p< .005).

4. Predicting SNSs users’ Life Satisfaction

A Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate if the key variables of the study would predict life satisfaction of Facebook users. The results of this analysis showed that the predictor variables explained a statistically significant amount of variance in life satisfaction scores (F[5,190]= 14.71, p < .001, R2 = .28, Adjusted R2=.26). In terms of the contribution of each predictor in the model, the results revealed that social comparison (β = .15, t[190]= 2.26, p = .025), FoMO (β = - .18, t[190] = -2.47, p = .014), and self-esteem (β = .38, t[190]= 5.19, p< .001) significantly predicted life satisfaction, even when controlling for potential confounding effects from participants’ age (β = -.02, t[190] = -.37, p = .712) and Facebook use (i.e., passive following) (β = .03, t[190] = .41, p= .681) (Table 2).

5. Discussion

The present study set out to investigate how passive following on Facebook, FoMO, self-esteem, social comparison, and age may affect life satisfaction. The results indicated that there was no statistically significant association between passive following and life satisfaction, thus not supporting H1 (i.e., passive following on Facebook will be negatively associated with life satisfaction). This finding supports previous research [24] which reported no link between these two variables. There are two potential explanations for this finding. Firstly, life satisfaction of SNS users may only be affected under specific patterns of SNSs usage, such as addictive use [49]. Secondly, passive following on Facebook might not produce detrimental psychological effects that are capable of hampering users’ wellbeing. The findings of this study did not find support for H2 (i.e., social comparison will be negatively associated with life satisfaction) as a significant positive correlation was found between social comparison and life satisfaction, suggesting that people who tend to compare themselves with others on Facebook are more likely to feel more satisfied with their lives. This finding is inconsistent with previous research [30,50] which indicated an association between social comparison through Facebook and low levels of life satisfaction among students. However, the present findings support the work of Buunkand, Gibbons [28] who found that people use Facebook for self-evaluation and self-improvement. Furthermore, the findings also provide evidence to support the social comparison theory [27] which has implications for how people engage with SNSs.

It can be speculated that the relatively high level of life satisfaction reported by the participants in the present study may be due to them using Facebook as a tool for self-improvement. Their age may have an impact on life satisfaction (the average age of participants in the present study was 31 years, which is closer to middle adulthood). These two factors may have helped participants overcome negative feelings potentially generated through social comparison. This lends to support to the UG theory [11], users actively use SNSs to fulfil their needs. Additionally, previous research [30] found that social comparison caused lower levels of life satisfaction among adolescents. Adolescents are more vulnerable to negative emotions through negative social comparison and typically experience lower levels of self-evaluation [31,32]. Future in-depth research investigating the possible consequences of online social comparison amongst adolescent SNS users is warranted.

The findings of the present study showed a significant negative correlation between FoMO and life satisfaction, which is in line with H3 (i.e., FoMo will be negatively associated with life satisfaction). This finding indicates that people who experience low levels of FoMO are more likely to be satisfied with their lives, a finding that mirrors those reported by Przybylski et al. [39] in which the same link was found. In addition, the present study found a significant positive correlation between FoMO and passive following. This finding supports H4 (i.e., FoMO will be significantly associated with passive following on Facebook) and is in line with previous studies, such as the study conducted by Przybylski et al. [39] in which FoMO was found to be positively associated with intense Facebook use, and the study of Buglass, Binder, Betts, and Underwood [51] in which FoMO was associated with increased SNS use. Taken together, these findings suggest that FoMO may emerge under specific forms of SNS use.

To investigate how SNS use may shape users’ life satisfaction, a multiple linear regression was conducted. The results showed that social comparison, FoMO, and self-esteem were significant predictors of life satisfaction, even when accounting for the effects of age and passive following on Facebook. This finding suggests that higher levels of social comparison, self-esteem, and lower levels of FoMO are associated with increased life satisfaction in SNSs users. The negative association between FoMO and life satisfaction supports previous research [39]. However, the positive association between self-esteem and life satisfaction in the context of SNS use challenges previous research [51]. Furthermore, the positive association between social comparison and life satisfaction supports the tenets of social comparison theory [27] as participants may be using Facebook for self-improvement, which contrasts with Lee [32] who reported links between social comparison on Facebook and negative feelings.

In the present study, passive following on Facebook was a common activity amongst participants. Passive following does not contribute to communication amongst users [6], and only provides the feeling of connectedness. A possible explanation as to why passive following may emerge amongst SNSs users could be related to the fact that the online friends an individual becomes connected to may not necessarily be the people with whom they wish to keep in contact. This can be particularly evidenced in users who use Facebook for professional purposes only and thus wish to have their work displayed to as many individuals as possible, including those they might not wish to be friends with. They may only be interested in obtaining information and services as proposed by the theory of purposive value [25]. Further research could examine the criteria people apply to adding friends on Facebook and if their choices and motivations change over time.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, the unbalanced ratio of female to male participants may indicate that the results are more representative of a female sample. Future research should aim to recruit equal numbers of females and males. Secondly, the results were based on self-report measures which can have an impact on the implications of the findings due to well-known effects (e.g., social desirability effects). Thirdly, the present study used a cross-sectional design, thus no causality can be inferred from the findings reported. In conclusion, the present findings make an important contribution to the research literature by showing that social comparison, FoMO, and self-esteem are significantly related to life satisfaction in the context of SNS use. The findings will benefit SNS users to better understand their online behavior and researchers who continue to investigate the psychology of SNS use. The results obtained will hopefully pave the way to future psychological research examining the impact of SNSs on users’ health and wellbeing.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.