1. Introduction

Baumrind suggested that parenting involves two basic and very different abilities, the ability to demand that the child behave in ageand culture-appropriate ways, and the ability to respond to his or her needs. Authoritarian parenting is high on demandingness and low on responsiveness, permissive parenting is high on responsiveness and low on demandingness, and neglectful-rejecting parenting is low on both dimensions [1]. Authoritative parenting strikes a successful balance between the two. According to Baumrind's conceptualization, authoritative parenting would lead to the best outcomes for most children in most environments, and the other styles would have deleterious effects.

A wealth of developmental research has supported Baumrind's theory. Authoritative parenting has been shown to be positively associated with academic achievement in children across many cultures [2], and negatively associated with internalizing behavior problems in children and adolescents [3], child overweight and obesity [4], and the development of externalizing behavior problems in children [5]. These meta-analytic studies also show that the longterm effects of other parenting styles tend to be detrimental. To summarize, in most studies, authoritarian parenting exercising harsh control is associated with the worst outcomes.

In the current study, in which only highly dedicated mothers participated, we measured three of the four parenting styles, permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian following [6] who suggested omitting neglectful parenting under these circumstances.

How and why do some individuals become more authoritative parents, whereas others lean more towards authoritarianism, permissiveness, or neglectful-rejection? The internalized blueprint of the “newly born parent’s” early infant attachment experience, or in other words the parent’s perception of, and response to the parenting that he or she received as an infant, may influence the parental style that individuals tend to develop.

A comprehensive review by Jones, Cassidy, and Shaver [7] leaves little doubt that this is indeed the case. This review presents over 60 studies assessing self-reported attachment styles in adults, and shows that secure (or less anxious and less avoidant) attachment is related to more sensitive and responsive observed parental behavior as well as to a more (self-reported) authoritative parental style.

The initial aim of attachment theory was to understand and explain the strong emotional connection between babies and their caregivers [8]. Hazan and Shaver [9] developed Bowlby’s thinking and suggested that the nature of this emotional bond is internalized over time by the infant and forms an interpersonal blueprint that guides his or her subsequent relational patterns. Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth developed Bowlby’s theory and proposed three basic attachment categories [10], to which Main and Solomon [11] later added a fourth. Bartholomew and Horowitz [12] extended attachment theory to adults and suggested that the four attachment styles that best describe adult relational attachment in close relationships are: secure, avoidant, anxious, and disorganized.

According to these theories of attachment, people who are securely attached seek intimacy, closeness and support in close relationships [13]. They can successfully regulate affect and tend to cope with stressful and difficult circumstances by drawing close to trusted others and seeking support from them [12].

People who are avoidantly attached strive for high levels of independence and tend to feel comfortable without close relationships. Stressful circumstances lead them to depend on themselves and their own self-regulatory capacities, rather than on close others [14].

People who are anxiously attached, seek close connections with others but have poor self-regulatory skills [14] and fear abandonment. They therefore tend to cling to others and strive to merge with them [12,9] . Stressful or threatening situations can trigger extreme and intrusive attempts to gain support that often prove unsuccessful and leave them feeling unsupported [14].

People with disorganized attachment are unable to develop trust in others, usually because trust was lacking in their early relationships and their caregivers were often abusive or neglecting [15]. They cannot be soothed by others, and lack psychological coping strategies necessary to deal with stressful and threatening circumstances [11].

In adult’s self-reported attachment, two styles are measured - anxious and avoidant [16], and they are used as continuous variables rather than as categories, with the understanding that being low on both results in having more secure attachment, while being high on both is the tendency to disorganized attachment.

Many factors influence the development of attachment styles. These include the relationship between infants and their primary caregivers, which emerges in the context of the internal and external resources of the primary caregiver, including his or her temperament, and the temperament of the child. Infant temperament is therefore an obvious contributor to attachment style formation [10]. As the infant grows and develops, other aspects of personality are formed and consolidated during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, which will affect the individual’s responses to the physical, cognitive, and emotional challenges of parenting.

Puff and Renk [17] showed that parenting styles were influenced by child functioning, mature parental personality as measured by the Five Factor Model (FFM), and parental temperament measured by Thomas and Chess [18] nine factors of temperament. Aval, Tahmasebi, and Maleki [19] found authoritative parenting to be negatively associated with the FFM Neuroticism and positively associated with Agreeableness and Extraversion. Kitamura, Shikai, Uji, Hiramura, Tanaka and Shono, [20] conducted a three-generation study of parenting. They assessed temperament and character of the second generation and concluded that the personality of men and women as measured by the temperament and character bio-psychosocial model of personality [21] mediated the inter-generational transmission of parenting styles. In their meta-analysis, Prinzie, Stams, Deković, Reijntjes, and Belsky [22] concluded that there is a small, replicable and significant relationship between maternal and paternal personality and parenting styles.

The temperament and character bio-psycho-social model of personality is particularly appropriate for use in a developmental approach. It posits two-tiers of personality: temperament, that is evident early in development and is pre-or un-conscious; and character, that develops after language acquisition and is therefore more accessible and potentially easier to modify [23]. The TCI measures four temperament traits: Novelty-seeking that taps curiosity, impulsiveness, and expansiveness, as well as a tendency to be disruptive and not follow the rules; Harm-avoidance that reflects a tendency to inhibit behavior so as to prevent harm and includes fearfulness, shyness, pessimism and fatigability; Reward-dependence that measures responsivity to social cues; and Persistence that assesses a tendency to be perfectionistic and ambitious, to withstand frustration and to work hard. Individual differences in temperament are related to individual differences in brain structure and function.

Character develops in transaction with significant others, and the wider culture, and is affected by the individual's pre-existing temperament. It is evident in children, reliably measurable in pre-teens and even more reliably measurable in adolescents. Three character traits are assessed by the temperament and character inventory (TCI): Self-directedness that includes responsibility, purposefulness, initiative, self-acceptance and good habits; Co-operativeness that includes accepting others, and being empathic, sympathetic, helpful and principled; and Self-transcendence that includes identifying with a transcendent entity, and therefore self-forgetfulness, and openness to spiritual experience [24]. All seven TCI traits have been shown to be highly heritable, and have some shared and some unique genetic variance [25]. Adaptive behavior is influenced by the combination of high and low temperament and character traits, with high PS, low HA, high SD and high CO, conferring physical and emotional resilience [26]. Whereas temperament can still change significantly during adolescence, character develops much more during this period; both are formed and stabilized earlier in girls than in boys [27]. In adults, on the other hand, both temperament and character tend to be generally stable [28,29] . This stabilization would be evident for most adults before they first become parents.

The purpose of the current study was to arrange the various influences reviewed here together in a developmentally informed sequence, and to test a model that posits that attachment style, followed by temperament and then by character would successfully and meaningfully predict parenting styles in adults.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The participants of the current study included 182 women, healthy community volunteers. Their mean age was 32.9 + 4.9, and that of their children 3.4 + 1.0. Most (95%) were married or cohabiting with the child's father, and most had average or above average SES (78.4%).

2.2 Instruments

- Temperament and Character was assessed using a 140-item version of the Temperament and Character Inventory [24, TCI- 140].The TCI-140 consists of the first 140 items of the Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised [24, TCI-R]. 136 of its items assess four temperament traits, three character traits, and four response accuracy/carelessness items which serve to test validity. Responses are ranked on a five-point Likert scale. In this study a Hebrew translation of the TCI-140 that has been shown to have solid psychometric properties was used [30]. The temperament trait Harm Avoidance (HA) is primarily an inhibitory tendency, and individuals high in HA are risk averse, pessimistic and fatigable. A sample item for HA is “I often feel tense and worried in unfamiliar situations, even when others see no cause for worry”. The internal consistency of HA in this study was α=0.88. The temperament Novelty Seeking (NS) is an excitatory inclination. Individuals high in NS are curious, exploratory, impulsive, irritable and expansive. A sample item is: “I often try new things just for fun or thrills, even if most people think it is a waste of time”. The internal consistency of NS in this study was α=0.64. The temperament trait Reward Dependence (RD) is the tendency of individuals to respond to social cues. Individuals high in RD are sentimental, open to warm communication, securely attached and dependent on social acceptance. A sample item is “I like to discuss my experiences and feelings openly with friends instead of keeping them to myself ”. The internal consistency of RD in this study was α=0.79. The fourth temperament trait is Persistence (PS) and individuals high in PS are ambitious, perfectionistic, hardworking, and frustration tolerant. A sample item is “I like a challenge better than easy jobs”. The internal consistency of PS in this study was α=0.84. The three character traits are Self- Directedness (SD), Cooperation (CO), and Self-Transcendence (ST). Individuals high in SD are purposeful, responsible, selfaccepting and resourceful. A sample item is “Often I feel that my life has purpose and meaning”. The internal consistency of SD in this study was α=0.88. Individuals high in CO are accepting of others, empathic, compassionate, helpful and principled. A sample item is “I like to help find a solution to problems so that everyone comes out ahead”. The internal consistency of CO in this study was α=0.78. Individuals high in ST are self-forgetful, transcendent, and spiritual. A sample item is “I often feel a strong sense of unity with all the things around me”. The internal consistency of ST in this study was α=0.89.

- Attachment was assessed by the Experience in Close Relationships - short version [16, ECR-S]. The structure of this 12-item questionnaire is based on Brennan, Clark, and Shaver’s [31] proposal that the four original typologies of attachment styles are best described in a two-dimensional space. The ECR-S subscales are, accordingly, avoidant attachment and anxious attachment, each comprised of six items, scored on a Likert scale between 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item assessing anxious attachment is “I’m worried that my romantic partner won’t care as much about me as I about him/her” and of avoidant attachment is “I want to get close to others but I keep withdrawing from them”. The ECR-S was found to have solid psychometric properties [16], equivalent to those of the original, 36-item, Experience in Close Relationships [31,ECR]. The authors advise using the ECR-S in its continuous form but also supply statistical guidelines to build the four original attachment styles suggested by Ainsworth [10,12] . The ECR was translated into Hebrew by Mikulincer and Florian [32], and the subset of ECR-S items from their translation comprised the Hebrew version of the questionnaire used in this study. The internal consistency of the anxious-attachment subscale was α=0.92, and of the avoidant-attachment subscale was α=0.91.

- Parental style was assessed by the Parental Authority Questionnaire [6, PAQ]. This 30-item self-report scale is composed of three subscales that correspond to three of the parental styles proposed by Baumrind [1]: permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative. Mothers responded to each item on a five-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The PAQ has adequate discriminant and criterionrelated validity [33]. A sample item from the permissive subscale is “I feel that in a well-run household, children should be free to behave as they see fit to the same extent as parents”; a sample item from the authoritarian subscale is “When I tell my child what to do, I expect immediate and unquestioning obedience”; a sample item from the authoritative subscale is “Whenever we establish a family policy, we discuss its rationale with the children”. The internal consistency of the three scales in this study were respectively α=0.86, 0.83, 0.90.

2.3 Procedure

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and a link for an online report including an informed consent form was sent to the participants by email. No remuneration was offered for participation. Participants who requested personal feedback on their personality profile based on their TCI were sent a short description by email.

2.4 Data Analysis

The associations between attachment, temperament, character and parenting styles were assessed using Pearson correlations. The mediating role of temperament and character in the progression of attachment styles to parenting styles was examined using structural equation modeling (SEM). AMOS, Version 23 for Windows was used for the SEM analysis and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 23) was used for the other analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Pearson correlations

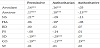

As can be seen from Table 1, both anxious and avoidant attachment were positively associated with both permissive and authoritarian parenting styles. Anxious attachment style was also inversely associated with the authoritative parenting style. Of the temperament traits, only Novelty-seeking and Harm-avoidance were associated with parenting styles. Novelty-seeking was positively associated with permissive parenting and Harm-avoidance was positively associated with authoritarian parenting. Of the character traits, Self-directedness and Co-operativeness were inversely associated with both permissive and authoritarian parenting and Co-operativeness was also positively associated with authoritative parenting.

To test the hypothesis that temperament and character would mediate the association between attachment and parenting styles, a structural equation model (SEM) was designed. As a combined rule for model acceptance, we chose the following values: NFI (Normed Fit Index) > .90 [34], and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) < .08 [35].

Attachment styles were entered as the independent variables, temperament and character were entered as mediating variables and parenting styles as predicted variables (see Figure 1). The Chi-square goodness-of-fit index was χ2 (32, N = 182) =42.65, p = .10); normed fit index (NFI) = .94; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) =.014; standardized RMR = .06.

As can be seen from Figure 1, avoidant attachment was positively associated with Harm-avoidance and inversely associated with Reward-dependence. Anxious attachment was positively associated with Novelty-seeking and Harm-avoidance and was inversely associated with Self-directedness and Cooperativeness. Noveltyseeking was positively associated with permissive parenting style, and negatively associated with Self-directedness and with both authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles. Harm-avoidance was negatively associated with Self-directedness. Reward-dependence was positively associated with Self-directedness, Cooperativeness and authoritarian parenting style. Persistence was positively associated with Self-directedness. Although Self-transcendence was initially entered into the model, was not significantly associated with any other indices, and was therefore excluded from the model. Selfdirectedness was negatively associated with Authoritarian parenting style. Cooperativeness was positively associated with Authoritative parenting style, and negatively associated with Permissive and Authoritarian parenting style.

4. Discussion

The model in Figure 1 presents a plausible and intriguing purported path, leading from internalized infant attachment to temperament, from attachment and temperament to character, and from all three to the authoritative, authoritarian and permissive parenting styles. The model’s excellent goodness of fit indices at test to its overall robustness.

The significant correlations we observed between attachment styles and parenting styles are in keeping with a large body of research that has established robust associations between attachment and parenting styles [7]. Nevertheless, there are no direct paths between the two in the structured equation model shown in Figure 1. A possible and plausible developmental explanation for the connection between attachment and parenting styles is, therefore, that this association is fully mediated by temperament and character traits.

The only personality trait not included in the model presented in Figure 1 is Self-transcendence. Although it was included in our original analyses, it was excluded from the SEM model because no statistically significant paths led to or from it. The character trait of Self-transcendence is measurable in children and adolescents. Scores tend to be relatively low at the end of adolescence and over young adulthood, but rise as this trait develops and expands over the second half of life, when generativity and meaning become more central to personal development [37]. This might partially explain why it did not relate meaningfully to the other variables in these young adults recently introduced to the role of parenting.

The busiest node of the SEM presented in Figure 1 is Selfdirectedness. This character trait is positively associated with the temperament traits of Persistence and Reward-dependence, and negatively with both Novelty-seeking and Harm-avoidance. This model therefore corroborates previous research suggesting that Selfdirectedness is related to a more dependable temperament profile [27]. Since it is also associated with a less authoritarian parenting style, the character trait of Self-directedness may protect mothers from developing an authoritarian parenting style. This protective influence could well stem from the importance of Self-directedness in emotional regulation, because the ability to deal constructively with one’s emotions facilitates a sustained focus on personally meaningful goals [39].

The character traits of Cooperativeness and Self-directedness have been jointly conceptualized as “maturity” [23,39] and contribute to adaptive, flexible and appropriate adult functioning. Since parenting is so central to mature adult functioning, the direct paths between these two character traits and parenting styles in the SEM model, with negative valences on the path to authoritarian parenting, are consistent with this conceptualization. Parenting is undoubtedly one of the most protracted and challenging roles undertaken by humans, with the most significant multi-generational outcomes. The results presented in this study suggest that parenting might be enhanced by interventions aimed at increasing character maturity.

The current study has several limitations that should be kept in mind when evaluating the results. First, the sample size is limited, and the data was self-reported by the mothers. Ideally this study should have been conducted as a longitudinal study. Whereas the variables in the model were arranged in sequence according to our best understanding of theory and development, the results would be more compelling had we been able to measure the attachment of the mothers as toddlers, their temperament during childhood, their character during early adulthood, and their parental style after the birth of their children (when in reality all the data was collected). So, whereas the model is consistent with developmental theory, it in fact presents cross-sectional data inserted into a theoretical chronological sequence.

In conclusion, a model consistent with maternal authority being predicted by maternal attachment tendencies mediated by temperament and character was shown to be robust. If these results withstand rigorous replication, they would have implications for adaptive maternal authority and for designing interventions aiming to improve maternal practices.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.