1. Introduction

Despite the fact that being exposed to trauma or stressful circumstances can negatively impact individuals in many ways, increasingly studies are showing that even amongst this suffering, positive changes and affects do sometimes result as well. Tedeschi and Calhoun [2] dubbed this process as Post-traumatic Growth (PTG). Thus, in this study we sought to clarify the predictors of wellbeing among a sample of tertiary students.

However, at least two controversies erupted surrounding this issue: whether PTG reflects true positive changes, and whether what is measured is truly growth (dubbed the validity controversy). Kunst [3] suggested that peritraumatic distress enables growth after substantial time has elapsed since victimization. Luszczynska, Durawa, Dudzinska, Kwiatkowska, Knysz, et al. [4] have also emphasized the defensive character of PTG, that is finding benefits in illness and changes in the function of these beliefs over time elapsing since diagnoses.

Kleim and Ehlers [5] found that PTG may be most relevant in trauma survivors who attach enduring significance to the trauma for their lives and show initial distress. Moderate levels of PTG do not seem to ameliorate post trauma psychopathology. Kira, Abourmediene, Ashby, Odenat, Mohanesh, et al. [6] indicated that PTG was not a significant predictor of any mental health symptoms and that PTG is different from growth in non-traumatic situations. The results suggest that it is important to analyze trauma profiles rather than single trauma.

Evans [7] found a high incidence of trauma among graduate students and low to moderate amounts of growth following trauma in 29% of the respondents. There does appear to be a relationship between having experienced trauma and achieving growth, specifically where the trauma experienced was of a horrific, shocking, and grotesque nature and relating to a total growth measure. What kinds of trauma are related to more specific kinds of growth was not made clear, however. For example, Taku, Kilmer, Cann, Tedeschi, et al. [8] suggested that the youth-reported growth does not simply reflect normative maturation. Multiple regression analysis, using participants who reported at least one traumatic event, indicated that deliberate cognitive processing appears to play an important role in PTG. Cultural and developmental aspects of these findings, as well as implications for research and applied work are discussed.

As indicated by Haidt [9], empirical literature seems to agree on at least three key potential benefits of posttraumatic growth, namely: (1) tapping into one’s own resourcefulness with a sense of empowerment; (2) better interpersonal relationships; and (3) a deeper change of one’s priorities and life’s perspective (appreciation of the present moment and of significant others).

On the other hand, as Park and Helgeson [10] indicated, research does not suggest a strong association between PTG and subjective wellbeing. More clarification work is thus required. For example, it is still debatable whether posttraumatic growth should be seen as a process or as an outcome variable.

Three main hypotheses were put forward by Helgeson, Reynolds, and Tomich [11], namely, (a) that PTG leads to positive life changes which improve well-being; (b) that PTG does lead to life changes but comes at the price of lowering well-being because it is a stressful journey, and finally, that PTG is a coping strategy which mediates the relationship between trauma and wellbeing.

Moreover, researchers are still unclear whether posttraumatic growth is a kind of resilience, or rather resilience plays a key role in the development of PTG. Bonanno and Mancini [12] explained resilience as an adaptive process that occurs in the wake of trauma, to be able to maintain a healthy psychological wellbeing. On the other hand, Tedeschi and McNally [13] indicated an inverse relationship between PTG and resilience, where highly resilient people experienced less PTG than less resilient people.

The intriguing question remains as to why some individuals experience more posttraumatic growth than others. Considering that personality traits and mood states have been consistently and significantly linked to PTG [14-15] in related studies, their unique contribution needs to be accounted for how a person manages to interpret life’s traumas, despite the suffering and challenges inherent in them [16] is crucial in understanding this process of posttraumatic growth. Thus, this study encompassed the relevance of personality variables, to further investigate its input and variance in the equation, to help clarify what impacts PTG in such circumstances.

Two main hypotheses were put forward in this study: first, that subjective well-being will correlate with key variables particularly with post-traumatic growth, and second, that PTG and spirituality would both have unique variance in predicting well-being among our sample with a history of trauma, even after controlling for other key variables. This would be particularly relevant considering that this study was done in a different culture from what is found elsewhere, thus having a unique meaning and considerations to local mental health professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Measures

2.1.1 Posttraumatic growth

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) was developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) [17] to assess any positive outcomes in people in view of traumatic occurrences. The PTGI is a 21-item inventory measure that tries to capture five domains or factors of growth, namely: one’s relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and a deeper appreciation of life. Items are rated on a 0 (I did not experience this change) to 5 (I experienced this change to a great degree) scale. Scores range from 0 to 105. The scale has acceptable test-retest reliability [17]. The short form (10 items) was used in this study (M = 32.27, SD = 7.70). Alpha coefficient was found to be 0.83.

2.1.2 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms

The PTSD Checklist, Civilian Version (PCL-C) was developed by Frank Weathers and his colleagues at the United States National Center for PTSD [18]. It is a 17-item self-report measure reflecting DSMIV symptoms and criteria of PTSD. An alpha of 0.94 and an overall correlation between total PCL-C and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores was found at 0.93 [18]. (M = 42.83, SD = 13.94). Alpha coefficient for the PCL-C for this sample was 0.70.

2.1.3 Personality

Personality was assessed through the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP), short version, developed by Goldberg [19-20]. The IPIP represents the NEO PI R. It is based on the Big-Five factor structure, namely: extraversion (tendency to experience positive emotions), agreeableness (tendency of be cooperative and agreeable in human relations), conscientiousness (degree to which a person is disposed to be dutiful to one’s role and obligations), emotional stability (tendency to experience positive emotions) and openness to experience (interest in a variety of internal and external experiences). Alpha coefficients for this study were found at 0.75, 0.70, 0.78, 0.80, and 0.66 respectively. The IPIP is scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (false) to 5 (always true). The full IPIP contains 300 items. It estimates a person’s standing on the 5-broad domains and 30 sub domains of personality [19].

2.1.4 Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 4-item scale developed by Cohen, Kararck and Mermelstein [21] as a global measure of perceived stress. Items are rated on a 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The PSS was designed for use with community samples. Items include “in the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” (M = 8.03, SD = 2.54, α = 0.80).

2.1.5 Wellbeing

Subjective well-being was assessed by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin [22]. It is a short 5-item instrument designed to measure global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one’s life. The authors believe that there is no one element to life satisfaction, but rather a recipe that includes a number of ingredients. Factors included in this short scale are: social relationships, work/school dynamics, personal satisfaction with self, spiritual life, growth and leisure. The authors indicated an alpha coefficient of 0.80. The alpha in this study was 0.82 (M = 47.94, SD = 9.97).

2.1.6 Spirituality

The Faith Maturity Scale (FMS), developed by Benson, Donahue and Erickson [23], has two subgroups: faith maturity vertical (FMV) and faith maturity horizontal (FMH). The measure has good internal reliability (α = 0.88). This scale measures the extent that participants seek spiritual growth. The FMS was selected for two reasons. First, its psychometric properties appear to be very acceptable. Secondly, it encompasses two main tenets of what spirituality to our knowledge must entail: love of the transcendent being or God and love of neighbor. At the core of the FMS is an understanding of faith as having “vertical” (inward journey, relationship to God), and “horizontal” (outward journey, relationship to others) dimensions, with an integration of both resulting in faith maturity. The authors described the measure as having a holistic sense focus, namely: integration of faith and life, holding life-affirming values, advocating social change, action and service [23]. The alpha reliability for the FMS in this study was 0.90 (M = 54.03, SD = 13.93).

2.1.7 Positive & Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), was developed by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen [24]. It is a 20 item scale comprises of two mood scales, measuring positive and negative affect. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, to 5 = extremely) to indicate the extent to which the respondent has felt this way in the indicated time frame. The authors report Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.90 for the Positive Affect scale and a range of 0.84 to 0.87 for the Negative Affect scale. Test-retest correlations for a two-month period ranged from 0.47 to 0.68 for Positive Affect, study was 0.72 for Positive Affect (M = 31.24, SD = 6.93) and 0.74 for Negative Affect (M = 19.56, SD = 7.08).

2.2 Procedures

After getting all ethical approval for this research, the questionnaire and a cover letter were sent by the University of Malta to a randomlyselected pool of students who upon entry as tertiary students indicated their willingness to partake in such studies. In total, 300 invitations were sent out. Inclusion criteria included students at the University of Malta who were presently enrolled in undergraduate degree. Potential participants were contacted by e-mail by the University of Malta. In total, 194 students responded, with a response rate of 65%. The e-mail included a cover letter signed by the researcher, explaining the main tenets of the study, together with a link to the questionnaire. Students could participate only once in the study. A code was assigned to every completed questionnaire that was returned, and then forwarded to the researcher. The researcher had no knowledge of the identity of participants, nor of their e-mail information. The study was on a voluntary and confidential basis. It was conducted during the first half of 2013. Participants had one week to respond.

2.3 Data Analysis

In this cross-sectional and correlational study, we sought the relationship of subjective well-being to posttraumatic growth in view of past trauma experiences and perceived stress by using Pearson correlation analysis. In particular, we investigated a sample of tertiary students’ perceived stress, past traumas, subjective well-being, faith maturity, positive and negative affect, and personality, together with demographic correlates.

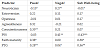

We hypothesized that spirituality and posttraumatic growth would both have significant unique variance in predicting subjective wellbeing among a sample of tertiary students with past trauma experiences. To determine this possibility, a series of hierarchical regressions were performed for all predictor variables with all components of subjective well-being entered separately as the criterion variable. Table 1 presents the beta weights for predictors of well-being scales.

3. Results

Participants (72% Female) were 194 tertiary students attending the University of Malta, with ages ranging from 18-32 years (M=21.60, SD=6.51). 85% of participants were single and 15% in a relationship or already married. Most respondents indicated as being Catholic, but only half were committed to their faith.

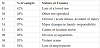

Table 2 shows the reported recent traumas of the participants in this study. 28% of participants experienced their trauma within one year from this study. 25% experienced their trauma from 1 to 2 years prior the study, 20% 2 to 5 years prior, while 27% had their trauma more than 5 years prior this study.

Faith maturity correlated positively with: subjective wellbeing (r194, t = 0.33, p < 0.01), positive affect (r194, t = 0.43, p < 0.001), agreeableness (r194, t = 0.26, p < 0.05), and also with post traumatic growth (r194, t = 0.64, p < 0.001). Research has established a consistent relationship between important life events and one’s tendency toward transcendence or spirituality [23].

Wellbeing correlated with positive affect (r194, t = 0.50, p < 0.001), posttraumatic growth (r194, t = 0.43, p < 0.001), negative affect (r194, t = -0.26, p < 0.01), perceived stress (r194, t = -0.43, p < 0.001). Wellbeing also correlated negatively with posttraumatic stress disorder (r194, t = -0.32, p < 0.01).

Extraversion correlated positively with all the personality domains and also with perceived stress (r194, t = -0.24, p < 0.05). Besides the above correlations, posttraumatic stress disorder correlated also with negative affect (r194, t = 0.36, p < 0.001), and perceived stress (r194, t = 0.39, p < 0.001). Finally, Posttraumatic growth correlated with positive affect (r194, t = 0.47, p < 0.001), agreeableness (r194, t = 0.27, p < 0.01), and with conscientiousness (r194, t = 0.27, p < 0.01).

It was hypothesized that spirituality and PTG would both uniquely contribute in predicting subjective well-being. Thus, a series of hierarchical regressions were performed for all predictor variables with all components of subjective well-being (Positive Affect, Negative Affect, and Subjective Well-being) entered separately as the outcome variable. Perceived stress (PSS) was entered in the first step in each regression analysis. It was only significant to negative affect.

Personality variables were entered as a block in the second step. Personality significantly predicted positive affect and subjective wellbeing, with a contribution range of 10% to 17%.

Faith maturity was entered into the third step, and contributed to positive affect and subjective well-being. Spirituality’s contribution ranged from 24% to 26%, over the input of perceived stress and personality.

Table 1 shows the beta weights which further underline the relationship between key variables with well-being scales. PTG related to all facets of well-being. On the other hand, spirituality related positively to positive affect and subjective well-being, but not to negative affect.

4. Discussion

Research suggests that spirituality relates positively to wellbeing, and to important life events [25,26] . This was also confirmed in this study, whereby it was found to positively correlate with all well-being scales, except negative effect, with personality and PTG.

Results suggested a personality profile of those who experienced PTG as high on conscientiousness and on agreeableness. A conscientious individual is guided by an inner sense of what is “right”. Such individuals typically share reputations for being meticulous, thorough and deliberate. Two aspects of conscientiousness are industriousness and orderliness. On the other hand, a profile high on agreeableness indicates altruism, trust and pro-social attitudes. Compassion and politeness are two aspects of agreeableness. Empathy, or genuine outlook, seems to be the key feature of such a personality. Adding this characteristic together with conscientiousness, the result would be a personality profile that shares positive correlations with the aspects of integrity. In sum, therefore, posttraumatic growth suggests a personality high on empathy and orderliness.

The next hypothesis was also supported. PTG and faith maturity both had unique variance in predicting well-being, even after partialling out the contribution of personality and perceived stress.

Perceived stress was significantly related to negative affect, as is expected, but not to positive affect or cognitive wellbeing. Interestingly, faith maturity contributed almost twice as much variance as personality to positive affect and cognitive wellbeing. Results showing the unique predictiveness of spirituality over and above personality were also found in other studies [27,28] . This continues to support research on the unique predictiveness of spirituality to wellbeing in view of trauma and perceived stress. On the other hand, faith maturity was not found related to negative affect.

PTG was related to all components of wellbeing. This variable predicts a plethora of feelings, and affects the individual in diverse ways, not just in producing a meaningful sense, but may also come at the price of scars from past emotional trauma. How a person manages to interpret life’s traumas, despite the suffering and challenges inherent in them [16] is crucial in understanding this process of posttraumatic growth. In this study, PTG explained from 18% to 33% of the variance for the separate subjective well-being components, after controlling for perceived stress, personality and faith maturity. Park and Helgeson [10] indicated that research does not suggest a strong association between PTG and subjective wellbeing. However, this was clearly not supported in this study.

It is important to highlight two important aspects of these results: first, these results were found even after partialling out key relevant variables, thus this truly reflects the unique predictiveness of spirituality and posttraumatic growth to holistic wellbeing. Secondly, the goal of multiple regression analysis is to find the contributions of all relevant variables, not simply the strongest variables. The aim is to provide the most comprehensive explanatory model possible.

That spirituality is different from subjective wellbeing is clear, but they do seem to complement each other. Results found in this study, and elsewhere strongly associated spirituality with subjective well-being and positive affect, but not to negative affect [29,30] . This may suggest that although spirituality may not be directly linked to a decrease of pain, it may have a unique impact in providing a framework through which painful experiences may be more easily borne [31-33].

Thus, spirituality may not help to directly reduce pain and suffering but seems to help in the increase of inner joy and somehow present a wider perspective through which the experience of pain is shared. This phenomenon may indicate that part of transcendence may act counter-intuitively. Many of the conceptual and practical approaches to spirituality have seen its role in terms of coping with psychological pain and trauma.

Ironically, multiple studies now show that, when controlling for personality, spirituality has minimal ability to reduce negative effects [34,35] . These results suggest that positive psychology would do well to continue its interest in spirituality and transcendence as key character strengths [36]. As Galea [37] suggested, the real value of spirituality from a functional psychological standpoint may well be its ability to enrich the meaning of human life.

Results further suggest that a healthy spirituality is a resource and is highly correlated to emotional wellbeing. Consistent with this finding, researchers [38-40], viewed spirituality as an important construct for wellbeing, particularly in countering traumatic ordeals in life. Some studies have found that whenever spirituality was factored in, it was always found significantly related to healthy outcomes, and inversely related to disorders [26,41,42]. In line with this, some results found that spirituality predicted a greater sense of wellbeing among abuse victims [43-46], and among nurses stressed out with burnout [47,48] .

If some trauma victims find inner peace through spirituality, then they would adhere to a more refined and personal spiritual journey, one that could enhance their healing.

Despite this, one must clarify that how exactly spirituality works as a buffer is not clearly established. Baumeister [1] notes that “suffering stimulates the need for meaning” because “people analyze and questions their sufferings far more than their joys”. Indications point at religious belief, rather than behavior, as being beneficial in providing a cognitive framework that might counter hopelessness [49]. Spirituality may ease the negative impact of trauma, by increasing affective well-being among individuals hurt somehow by trauma.

Because this study is correlational in nature, no inferences of causality can be made from this study. Moreover, one must remember this study’s reliance on self-reported and recalled data, which may have added further bias. Lastly, considering that the mean age of this sample was rather young (21.60), together with the fact that respondents were all tertiary students, one can outline the fact that results pertain to a rather skewed population in terms of life’s experience and trauma exposure. It is hoped that the next step would be a study considering a cross-sectional sample, thus representing better the general population. Hopefully, this would encompass a more varied history of traumas.

This study’s strengths are also noteworthy as they include the exploratory nature of the impact of PTG among Maltese students. The multidimensional focus of the study, in bundling together key and relevant variables is yet another strength.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study clearly points at the relevance of posttraumatic growth for the promotion of holistic wellbeing to trauma victims, even among a cross-cultural population of tertiary students. Moreover, it is noteworthy that spirituality was also found to predict the well-being of people with a trauma history, by increasing affective well-being and producing a wider perspective through which trauma may somehow be more easily experienced. This is of utmost importance particularly for mental health professionals to factor spirituality in their practice, especially when clients indicate its importance to them.

Competing Interests

The author declare that there is no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the participants in this study for their valuable contribution despite having gone through emotionally charged past situations and events.