1. Introduction

Happiness is defined as a prevalence of positive over negative affect and a satisfaction with life as a whole [1,2]. The adaptation-level theory suggests that people judge the pleasantness or unpleasantness of events or circumstances based on the positive and negative experiences of the individual [3]. According to this perspective, habituation makes extreme circumstances appear more normal to the individual, hence, in other words, happiness is subjective as individuals’ happiness and unhappiness could depend on how one judge the pleasantness of events or circumstances.

Gender roles and attitudes have shown to play an important role to signify gender-specific responsibilities and beliefs [4], which goes further than playing a role and carrying out duties [5]. Stereotypical portrayals of men and women roles persists till today [4], for instance, traditionally, men usually are the bread-winners, while, women typically enact the caretaker roles’ at home as a mother and a wife [6]. Therefore, women are usually sensitive to the needs of others and emotional expression [6], and they also have a tendency to report more extreme positive and negative feelings. There have been marked changes in gender role attitudes and responsibilities. For instance, men and women are increasingly open to women pursuing education and career goals and men helping with the housework [4]. With the increasing changes in gender attitudes and gender roles, young men and women are expected to work outside the house, and to expect women to work more for family and household chores [4,7,8].

2. Happiness and Gender

Previous studies also reveal that gender was related to subjective well-being that women tended to report higher happiness than men [6,9-12]. For example, in a sample of 600 Taiwan Chinese people, women scored significantly higher than men on happiness measures (Women: M = 70.65, Men: M = 66.95; t = 1.97, p < 0.05) as well as with greater variance (Levene’s p < .001) [13]. Similar findings were also reported in studies of subjective well-being [14-18], suggesting that it is a cross-cultural property [19]. Besides, women tended to score higher than men on measures of neuroticism and depression [20]. For example, women were found to experience distress 30 percent more often than men and women tended to express negative emotions more often and more freely than men [21]. Women also tended to experience more depression even though they were just as happy as men [22].

3. Happiness and the Big Five

In addition to gender roles and socialization, recent studies have also showed that dispositional factors, such as gratitude and optimism could play a vital role in keeping high subjective well-being (SWB) and low depression [23-26]. Abundant studies have been conducted in the past to explore the relationship between the big five and happiness [27-30]. For example, in a study of 423 Chinese university students, extraversion and neuroticism were found to predict happiness significantly [30]. In addition, extraversion was significantly and positively correlated with leisure satisfaction, and the opposite was true for neuroticism. In another study of 235 American university students, extraversion was found to predict happiness whereas neuroticism was found to predict unhappiness [31]. Extraversion was also found to be positively correlated with positive affect and to be negatively correlated with negative affect [31]. Moreover, extraversion and neuroticism predicted happiness and depression mediating through self-esteem [31].

Eysenck once remarked [32]; “Happiness is a thing called stable extraversion” (p. 87). Chamorro-Premuzic, Bennett and Furnham [33] argued that personality traits were “the most robust predictors of happiness”. They reported that happiness was positively correlated with extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. These personality traits (e.g., extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness) explained a considerable amount of variance in happiness [33]. DeNeve and Cooper [34] concluded that extraversion and agreeableness were the two most reliable predictors of positive affect while neuroticism was the most reliable predictor of negative affect and life dissatisfaction. Cheung and his colleagues [20] also reported that neuroticism and depression are closely related. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the interplay of the big five among subjective happiness and depression.

4. Aims of This Study and Hypotheses

This study aims to investigate how gender affects happiness and depression among Chinese people. Based on previous studies, we propose two general hypotheses for this study, i.e., women tended to report higher happiness and higher depression than men (H1); extraversion would mediate women’ experience of subjective happiness and depression whereas, neuroticism would mediate women’ experience of depression (H2).

5. Method

5.1 Participants

Five thousand, six hundred and forty-eight students between the ages of 17 and 29 (2180 men and 3198 women and 193 unspecified gender) were recruited from universities in China. All the students were university students.

5.2 Measures

Subjective Happiness Scale: Subjective happiness scale consists of 4 items (e.g., “In general, I consider myself…”, “Compared with my peers, I consider myself…”) [35]. A total of 4 items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 and 7 represents “not a very happy person, less happy, not at all” and “very happy person, more happy, a great deal”, respectively (α=.74).

Self-Rating Depression Scale: The Self-Rating Depression Scale [36] consisted of 20 items (e.g., “I feel down-hearted and blue”, “Morning is when I feel the best”) on a 4-point scale where 1 represents “occasionally” and 4 represents “always” (α=.75).

The Five Factor Model: The ten-item Personality inventory (TIPI) [37] consisted of 10 items to measure the Five Factor Model personality domains. Participants were required to rate on the self-report of how they viewed themselves on a 7-point scale where 1 represents disagree strongly and 7 represents agree strongly on all 10 items (e.g., “Extraverted, enthusiastic”, “Critical, quarrelsome”).

5.3 Procedures

Data were collected through questionnaires via a convenience sampling and were completed on a voluntary basis. The students completed these questionnaires in their free time. The questionnaires took approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete.

6. Results

6.1 Gender difference on depression and happiness

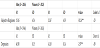

Results indicate that women score significantly higher than men on subjective happiness (M = 20.47, SD = 4.39) and depression (M = 41.63, SD = 8.14) ( Table 1). This supports hypothesis 1 of this study that women would report higher happiness and higher depression than men.

Results indicated that women scored significantly higher than men across the Five Factor Model (FFM), including, openness (t=2.83, p<.01), conscientiousness (t=-2.65, p<.01), extraversion (t=-3.57, p<.001), agreeableness (t=-10.32, p<.001), and neuroticism (t=-3.97, p<.001) (Table 2).

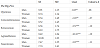

Subjective happiness was significantly and positively correlated with openness (r = .25, p < .001), conscientiousness (r = .20, p < .001), extraversion (r = .35, p < .001), and agreeableness (r = .25, p < .001) (Table 3). Subjective happiness was also negatively correlated with neuroticism (r = -.20, p < .001). Besides, depression was significantly and negatively correlated with openness (r = -.21, p < .001), conscientiousness (r = -.21, p < .001), extraversion (r = -.10, p < .001), and agreeableness (r = -.10, p < .001). Depression was negatively and positively correlated with neuroticism (r = .20, p < .001). Generally, subjective happiness was negatively correlated with depression (r = -.34, p < .001).

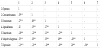

We then conducted multiple meditational analyses using the 5,000 bootstrap samples and a bias corrected confidence interval to examine mediation effect of personality [38]. The mediator is significant when the 95% confidence intervals (CI) do not contain zero. For subjective happiness, as shown in Figure 1, extraversion significantly mediated the relationship between gender and subjective happiness (95% CI = .03 .10). Also, neuroticism significantly mediated the relationship between gender and subjective happiness (95% CI = -.06 -.02). For depression, neuroticism significantly mediated the relationship between gender and depression (95% CI = .03 .10). Therefore, the results partly support hypothesis 2 that extraversion mediated women’ experience of subjective happiness and depression whereas neuroticism mediated women’ experience of depression.

7. Discussion

Results indicated that women were found to report significantly higher happiness and depression than men. These results echoed previous findings that women tended to report higher happiness [11,12] as well as higher depression [39-41] whereas men tended to report higher loneliness and lower emotional expressiveness [39-42]. This could be due to that men tended to express emotion associated with power and status such that their masculinity and social status would not be threatened [42-44]. Women, on the other hand, tended to express more emotional feelings, like gratitude and happiness [45,46]. This could be attributed to the gender role ideology that women tend to be sensitive to the needs of others and express their emotions more openly [4,6] and women also have a tendency to report more extreme positive and negative feelings.

Furthermore, the Chinese perspective conceptualizes happiness with “being content with one’s lot and feeling sincerely thankful for whatever life brings” [47]. This could indicate that women may have a tendency to be content with whatever life brings to them more easily than men. Happiness is conceived differently in every society of which different cultural values determine different understandings of happiness [47-49]. In Chinese society, for example, the Chinese characters of Fu-qi or Fu refer to happiness, which includes material abundance, physical health, a virtuous and peaceful life [49]. The Daoist Yin-Yang theory promotes a state of homeostasis such that happiness is achieved in harmonizing conflicts or contradictions with one’s surroundings [50]. The Confucian ethics of moderation calls for cultivation of internal harmony of he to achieve interpersonal happiness [51]. This goes to say that for the Chinese, happiness and unhappiness are always present. Secondly, extraversion and neuroticism were found to mediate the gender-happiness link and gender-depression link, respectively. This finding echoed previous studies that women were more emotional than men [11,52], and that extraversion and neuroticism could influence the link between gender and happiness as well as depression [53,54]. After all, extraversion has been a reliable predictor of positive affect, such as happiness [34]. For the Chinese people, it is rare that intense hedonic emotions are expressed even though they are acknowledged as a part of the happiness experience [47] . In the present study, extraversion did account for a significant amount of variance in the relationship between gender and subjective happiness.

Moreover, neuroticism was found to mediate the relationship between gender and depression, which is consistent with previous findings that neuroticism was more predictive of negative affect [34,54]. As neuroticism was a strong predictor of depression, it accounted for, in the present study, a significant amount of variance in the relationship between gender and depression as well [27,55,56].

Taken together, these findings show that gender seems to exert the similar pattern of impact on happiness and depression for the Chinese as it did for the Westerners. This came as no surprise as it has been argued that nowadays, neither Hong Kong, Mainland China, nor Taiwan Chinese could claim a pure heritage of Chinese traditions and cultural values due to the increasingly greater impact brought in by Western cultures to Eastern cultures, such as economic globalization, political interactions, strategic alliance, and systemic cultural communications from greater impacts [47,57-61].

8. Limitations

This study generated some really intriguing findings in terms of the gender difference on happiness and depression among Chinese undergraduates, with regard to the mediating role of the FFM. However, there are several limitations that need to be addressed in future researches. First of all, even though the present sample size is very big, it includes a homogeneous group, i.e., university students. So it is suggested that future studies ought to consider including samples from different walks of life to verify the present findings. Secondly, the present study used self-report measures; in so doing, participants might fill in the questions in a social desirable way. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies use other ways of data collection to cross-validate the findings. Thirdly, the present study sampled Chinese undergraduates only, future studies ought to recruit students from other countries or societies to justify the cross-cultural validity of the present findings. Last but not the least, future studies ought to examine more variables, such as, to test the directions of the relationship. To conclude this paper, we would like to quote a widely cited quotation from Freud: [The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is “What does a woman want?”] (Sigmund Freud: Adapted from The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud by Ernest Jones, 1953). This may be the ultimate answer or question to this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.